ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: to estimate the indirect cost of maternal death from the perspective of society.

METHODS: A cost-of-disease study was conducted using the human capital approach, which imputes as a productivity cost the lost earnings for each woman due to premature death and the potential years of life lost (PYLL) based on life expectancy at birth. All maternal deaths of residents of the First Macroregion of Pernambuco that occurred in 2012 and 2017 were included, extracted from the Mortality Information System, post investigation and discussed by the Maternal Mortality Comitee. PYLLs were calculated, as were costs based on the average nominal per capita income for the region in Brazilian currency, Real (R$), later converted to US Dollars (US$) and International Dollars. The cost of lost productivity was adjusted by the discount rate (3%) to obtain the net present value.

RESULTS: there were 119 maternal deaths, 59 in 2012, with 2,532 PYLL, with an indirect cost of US$ 24,681,888.92. In 2017, there were 60 maternal deaths, 2,395 PYLLs, with an indirect cost of US$ 18,326,149.33. Applying the discount rate, the value rose to US$ 31,605,158.76 (2012) and US$ 23,991,984.31 (2017).

CONCLUSION: maternal mortality causes high economic losses to society and increases PYLL, findings that are relevant to the management of policies aimed at women's health in the pregnancy and postpartum cycle.

Keywords:

Cost and cost analysis, Maternal mortality, Life value, Potential years of life lost, Health evaluation

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: estimar o custo indireto da morte materna na perspectiva da sociedade.

MÉTODOS: realizou-se estudo do tipo custo da doença utilizando a abordagem do capital humano, que imputa como custo de produtividade o ganho perdido por cada mulher devido à morte precoce e os anos potenciais de vida perdidos (APVP) baseados na esperança de vida ao nascer. Incluíram-se todos os óbitos maternos das residentes da I Macrorregião de Pernambuco, ocorridos em 2012 e 2017, extraídos do Sistema de Informação sobre Mortalidade pós-investigação e discussão no Comitê de Mortalidade Materna. Calcularam-se os APVP, os custos pelo rendimento nominal médio per capita para região na moeda brasileira, real (R$), depois convertido para dólares, americano (US$) e internacional. Ajustou-se o custo da perda de produtividade pela taxa de desconto (3%) para obtenção do valor líquido presente.

RESULTADOS: ocorreram 119 mortes maternas, 59 em 2012, com 2.532 APVP, com custo indireto de US$ 24.681.888,92. Em 2017, houve 60 óbitos maternos, 2.395 APVP com custo indireto de US$ 18.326.149,33. Aplicando-se a taxa de desconto, o valor passou a US$ 31.605.158,76 (2012) e US$ 23.991.984,31 (2017).

CONCLUSÃO: a mortalidade materna produz elevadas perdas econômicas para a sociedade e aumenta os APVP, achados relevantes à gestão de políticas direcionadas à saúde das mulheres no ciclo gravídico puerperal.

Palavras-chave:

Custo e análise de custo, Mortalidade materna, Valor da vida, Anos potenciais de vida perdidos, Avaliação em saúde

IntroductionMaternal death is a reflection of the absence of the right to health in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, a violation of human rights,

1 and an individual tragedy that generates tangible and intangible costs for society, the health system, and, in particular, for families.

2Most maternal deaths occur in the poorest communities and are usually due to preventable causes. They occur as a result of difficulties in accessing the health care system associated with failures in prenatal, childbirth, and postpartum care, which are exacerbated by social and individual vulnerability. The probability of a woman under the age of 15 dying from a maternal cause is 1:51,300 in Italy and 1:18 in Sudan.

3Given the severity of the problem, the United Nations has included targets for its reduction in international agreements, such as the Sustainable Development Goals, aiming to achieve a global Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) of 70 deaths per 100,000 live births (LB) by 2030. In 2017, in Latin America, Chile, Uruguay, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Cuba had much lower MMRs than Brazil (60.0 deaths per 100,000 LBW),

4 where estimates for 2009-2011 in the Northeast, were 80.8 per 100,000 LB and, for Pernambuco, 63.3 per 100,000 LB.

5There are many epidemiological studies on maternal mortality, but few address the economic dimension, relating costs to maternal morbidity and mortality, and these are more frequently found in middle- and low-income countries.

6-9 Economic studies cover both tangible and intangible costs. Direct tangible costs relate to medical and hospital expenses and non-medical and non-hospital expenses, while indirect tangible costs relate to economically measurable costs. Intangible costs are related to pain and suffering due to loss, usually measured in terms of quality of life.

10Indirect costs relate to the time a person was deprived of work and leisure due to illness and premature death and its impact on the national productive mechanism. These are calculated from the perspective of society and also include the costs to families. The value of the future income of these deceased women is a proxy for their contribution to society, assuming that the person could earn a constant amount throughout their productive life if they had not died prematurely.

10Despite the lack of consensus on the definition and methodologies of studies on the cost of maternal health services, there is agreement on the calculation of indirect productive losses, which should be included in these studies. However, these are not uniform.

9-12 There are three methods for estimating indirect costs: the human capital method, recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health; the friction method; and the

Washington Panel method.

10 These economic studies are necessary for the organization of women's health care, empowering managers to plan priority interventions on the political agenda, as well as social movements in the pursuit of rights. Thus, this study aimed to estimate the indirect costs of maternal death from the society's perspective in the State of Pernambuco, in the Northeast of Brazil.

MethodsA cost-of-illness study was conducted

13 to estimate the indirect costs of maternal deaths using the human capital approach,

10 as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO).

14 All deaths of women residing in the First Health Macroregion of Pernambuco between 2012 and 2017 were included. This region comprises 71 cities and the archipelago of Fernando de Noronha, corresponding to 5.4 million inhabitants, which represents more than 50% of the population in the State in the period, of which 33.7% were women of childbearing age (10 to 49 years).

15A total of 119 maternal deaths were identified, 59 in 2012 and 60 in 2017, in the Mortality Information System of the Pernambuco Health Secretariat, already investigated by hospital and city epidemiological surveillance and discussed by the Maternal Mortality Study Committees

of the State and the city of Recife, the capital.

16To determine the costs, the potential years of life lost (PYLL) were calculated. This study adopted the life expectancy for women at the time, which was 70 years as a limit, according to the Pernambuco State Database

17 and the human capital approach,

10 which imputes the cost of each woman's loss of productivity due to illness, disability, or premature death and monetizes these losses based on the present value of their income. The value of the future income of the victims of death is a proxy for the contribution that these women would make to society if they were working in full health and with constant income.

10,12 PYLL is an indicator applied in the comparison of causes of premature mortality and was calculated using Romeder and McWhinnie's technique.

18This technique uses an age limit based on the average life expectancy of the population, and to estimate the PYLL, deaths are organized into five-year age groups (10-14; 15-19; 20-29; 30-39, and 40-49 years). Next, the midpoint of the groups is calculated by adding the youngest and oldest ages in the group and dividing by two. This midpoint is subtracted from the age limit (in this case, 70 years old) and the resulting difference is the years of life lost in each age group. This number is multiplied by the number of deaths in each group, and the result is the PYLL.

To allow comparison of PYLL with other studies in different countries, the PYLL coefficient or ratio is used, which is the ratio between the total PYLL and the population of each group per 1,000 or 100,000 women.

To estimate the indirect cost, the indicator selected was the average nominal income from all jobs, usually received per month by people >14 years of age employed in the reference week with income from work, calculated by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics based on data from the Continuous National Household Sample Survey.

19 The value of this indicator for the resident population of the Recife Metropolitan Region in 2012 (R$1,660.00) and 2017 (R$2,113.50)

19 was multiplied by the PYLL for the age group. Thus, the cost of total productivity loss was calculated per capita and by age group of death in the selected years, in Brazilian currency, Real (R$).

For international comparison purposes, these costs were converted to US Dollars at the Brazilian Central Bank exchange rate on the last day of 2012 and 2017 (US$1.00 = R$2.0435 and R$3.3080, respectively).

20 The costs in R$ were also converted to International Dollars (Int$) at the rates (1 Int$ = R$1.61 in 2012 and R$2.21 in 2017), since some countries publish their results in this currency. The International Dollar is an indicator used to equalize the purchasing power of different currencies around the world and uses purchasing power parity (PPP). The PPP conversion factor is a price deflator and currency converter that eliminates the effects of differences in price levels between countries.

21The discount rate was applied to the total indirect cost for each year to obtain the future value (FV) in the years studied using the formula [FV=CV (1+discount rate)], where CV is the current value for the respective years, 2012 and 2017. This rate is indicated when there is a need to compare values at different points in time,

11 and the result is the net present value of this future cost. Discount rates of 5% per year were applied, as recommended by MSB,

10and 3%, also called the social discount rate, as a base case for costs.

11This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the

Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira by opinion N

o. 2,457,335/2017, with certificate of presentation for ethical review (CAAE) N

o. 72815317.4.0000.5201.

ResultsIn the First Health Macroregion of Pernambuco, there were 119 deaths in the years analyzed, and the average years lost per woman was 43 (2012) and 40 years (2017).

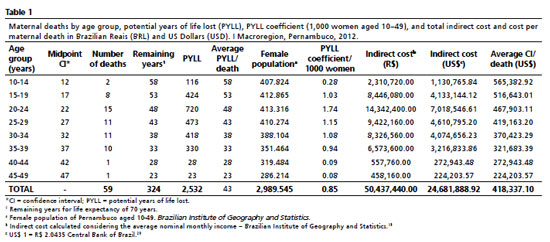

The results for 2012 show that 59 women died from maternal causes across various age groups, totaling 2,532 PYLL and a PYLL coefficient of 0.85/1,000 women. The highest number of maternal deaths occurred in women aged 20-24, who accumulated the highest PYLL (720), with the highest PYLL coefficient (1.74/1000 women) and the lowest 0.08 and 0.09 for the 40-44 and 45-49 age groups. The 59 premature deaths from these causes corresponded to a loss of productivity worth US$ 24,681,888.92, with an average loss per death of US$ 418,333.10 (Table 1).

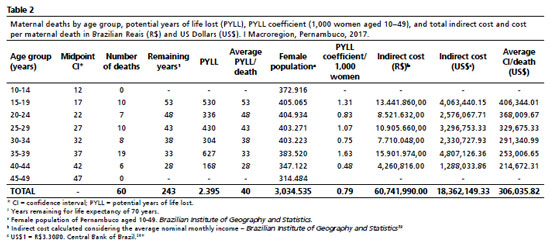

In 2017, there were 60 deaths, none in the extreme age groups (10-14 and 45-49), with 2,395 PYLL and a PYLL coefficient of 0.79/1,000 women. The highest number of deaths (19) and PYLL (627) were among women aged 35-39, with a PYLL coefficient of 1.63/1000 women, double the total found for the sample analyzed. Deaths of women from maternal causes totaled a productive loss of US$ 18,362,149.33 and an average value of US$ 306,035.82 per maternal death (Table 2).

Applying a discount rate of 5% in 2012, the cost was found to be US$ 27,710,356.69 for the future loss value of the 59 deceased women, and with a 3% increase in the rate, the value rose to US$ 31,605,158.76. In 2017, with a 5% discount, the indirect cost was US$ 20,969,574.53, equivalent to future losses, and with the social discount (3%), the indirect cost rose to US$ 23,991,984.31. Converting the losses from Brazilian Reais (R$) to International Dollars (Int$), the result for 2012 was Int$ 31,327,602.48 and for 2017, Int$ 27,485,063.35 (Table 3).

DiscussionThe 119 maternal deaths in the First Macroregion of Pernambuco resulted in high PYLL, with greater losses in the 20–24 age group in 2012 and the 30–35 age group in 2017, highlighting the impact of premature death among women of productive age. The value of the loss of productivity was higher when expressed in Brazilian Reais (R$) than in US Dollars (US$), reflecting the devaluation of the Brazilian currency during the period. The variation was 38.2% in Dollars and 27.1% in International Dollars (Int$), demonstrating the usefulness of conversion by purchasing power parity for international comparisons.

In high-income countries, such as Canada, PYLL are widely used to monitor premature mortality and inform health policies.

22 The application of this indicator to maternal deaths, although uncommon, allows for the estimation of economic losses and the evaluation of health system performance, especially in contexts of social vulnerability.

23,24 Economic losses to society are greater when death occurs early, as in the present study, with a greater financial burden due to its occurrence during productive age, consequently resulting in higher PYLL and higher cost per death for health systems.

23,24The indirect costs of maternal deaths represent a significant burden of economic losses to society, especially in middle- and low-income countries, where productivity losses are greater.

24 Monitoring PYLL and productivity losses makes it possible to evaluate policies, identify advances and challenges, guide multisectoral interventions, and strengthen advocacy for greater investment in maternal health.

24Some studies on maternal deaths and global disease burden use PYLL and calculate the costs of productivity losses by income; others use GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita.

4,25 African studies indicate that maternal deaths reduce regional GDP by billions of Dollars, revealing the economic role of women.

24 In Republic of Cabo Verde, between 2016 and 2020, maternal causes accounted for 0.8% of female deaths, with 1,183 PYLL and a cost of US$ 26,116.00 per death, the highest average cost among the indirect costs of all causes, ten times lower than that observed in Pernambuco.

23 In Mexico, a hospital study of 49 maternal deaths between 2011 and 2014 estimated 1,535 PYLL and an average of 31 years lost, lower than the Pernambuco average (40 years) in a population-based study.

7The 2016 Global Burden of Disease recorded a coefficient of 166.7 PYLL standardized by age and maternal causes per 100,000 maternal deaths,

25 lower than that observed in this study (174.2 and 163.4/100,000 in the age groups 20–24 in 2012 and 35–39 years in 2017, respectively), reinforcing the magnitude of the economic and social impact of early maternal deaths in the region analyzed.

The statistical value of a life, (SVL), expresses society's willingness to pay for the prevention of deaths and is essential data for calculating the benefits of policies that affect the risk of death or its excess. In Brazil, this approach has not been identified in cost-benefit studies, specifically for the prevention of maternal death, as in Ecuador

26 and the United States of America (USA).

27 These countries applied this concept to maternal mortality, estimating values of US$ 352,000.00 per life and US$ 176.00 per year for the prevention of maternal deaths, respectively.

26,27 These findings show that the costs of productive losses outweigh investments in prevention. While the US recorded US$7.9 billion in economic losses and 32,824 PYLL in 658 maternal deaths (2018–2020),

27 the First Macroregion of Pernambuco had US$43 million in losses and 4,927 PYLLs for 119 deaths, confirming the significant economic burden even in a regional context.

The indirect economic benefits of effective health intervention mean gains for society, given that recovered women are likely to return to work and ensure productivity.

24This study has limitations inherent to partial analyses of the cost of the disease, as it does not include direct medical and non-medical costs (care, family, or funeral costs) or indirect costs of absenteeism due to gestational morbidity, nor time lost by family members to accompany the woman.

13,26 Another limitation refers to the use of a static model, typical of these studies, which does not incorporate the effects of deaths on human capital and economic growth.

13,26 In addition, domestic and family care work, invisible in national accounts despite its economic and social value, was not taken into account. This exclusion tends to underestimate the real impact of female productivity losses, which may limit the adequate allocation of financial and technical resources for life-saving maternal health services.

28,29One strength is the quality of vital information in the region, where all female deaths are investigated by maternal mortality committees, minimizing underreporting, especially of late deaths. It should be noted that under Brazilian law, all maternal deaths must be discussed and analyzed by the CEMM.

16Although intangible losses, the cost of pain and suffering of family members before death and mourning, have not been considered, it cannot be said that the economic value is zero. However, relevant data on these variables could only be obtained through research on willingness to pay.

26The attribution of the average nominal female income sought to compensate for the absence of valuation of unpaid work, a common strategy in social cost studies.

24,25 The study reinforces that maternal mortality causes significant economic losses and that the inclusion of indirect costs broadens the understanding of the social impact of maternal death, supporting public policy decisions aimed at caring for women during pregnancy and the pregnancy-puerperal cycle.

Maternal mortality causes significant economic and social losses to society. The measurement of indirect costs and PYLL highlights the impact of premature deaths of women at reproductive age. These results reinforce the need for integrated health and social protection policies aimed at preventing avoidable deaths and valuing the economic and reproductive role of women in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle.

References1. Freitas-Júnior RAO. Mortalidade materna evitável enquanto injustiça social. Rev Bras Saúde Mater Infant. 2020; 20 (2): 615-22.

2. Souza JP, Belissimo-Rodrigues F, Santos LL. Maternal Mortality: An Eco-Social Phenomenon that Calls for Systemic Action. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2020; 42 (4): 169–73.

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva: WHO; 2019. [access in 2019 Jul 20]. Available from:

https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Maternal_mortality_report.pdf4. United Nations. General Assembly, 2015. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 (A/RES/70/1). Transforming our world: the 20230 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York; 2015. [access in 2019 Jul 20]. Available from:

https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf5. SzwarcwaldCL, Escalante JJC, Rabello Neto, DL, Souza Júnior PRB, Victora CG. Estimação da razão de mortalidade materna no Brasil, 2008-2011. Cad Saúde Pública. 2014; 30 (Supl. 1): S71-83.

6. Moran PS, Wuytack F, Turner M, Normand C, Brown S, Begley C,

et al. Economic burden of maternal morbidity - A systematic review of cost-of-illness studies. PloSOne. 2020; 15 (1): e0227377.

7. Santamaría BAM, Gutiérrez Ramírez JA, Herrera Villalobos JE, Ibarra Estrada E, López Esquivel MA, Zerón HM. Costo de la Atención Hospitalaria y Años de Vida Perdidos por la Muerte Materna. Salud Adm. 2018; 5 (13): 23-30.

8. Kes A, Ogwang S, Pande RP, Douglas Z, Karuga R, Odhiambo FO,

et al. The economic burden of maternal mortality on households: evidence from three sub-counties in rural western Kenya. Reprod Health. 2015; 12 (Suppl. 1): S1-3.

9. Banke-Thomas A, Abejirinde IO, Ayomoh FI, Banke-Thomas O, Eboreime EA, Ameh CA. The cost of maternal health services in low-income and middle-income countries from a provider's perspective: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020; 5 (6): e002371.

10. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia. Diretrizes metodológicas: Diretriz de Avaliação Econômica. 2

a ed. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2014. [access in 2019 Jul 20]. Available from:

https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/diretrizes_metodologicas_diretriz_avaliacao_economica.pdf11. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 4

a ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

12. Gonçalves MA, Alemão MM. Avaliação econômica em saúde e estudos de custos: uma proposta de alinhamento semântico de conceitos e metodologias. Rev Médica de Minas Gerais. 2018; 28 (Supl. 5): e-S280524.

13. Jo C. Cost-of-illness studies: concepts,scopes and, methods. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014; 20 (4): 3327-37.

14. Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS). CID-10 Classificação Estatística Internacional de Doenças e Problemas Relacionados à Saúde. 10

th revisão. São Paulo: EDUSP; 1995.

15. Secretaria de Saúde do Estado de Pernambuco. Plano Diretor de Regionalização. Pernambuco; 2011. [access in 2019 Jul 31]. Available from:

http://portal.saude.pe.gov.br/sites/portal.saude.pe.gov.br/files/pdrconass-versao_final1.doc_ao_conass_em_jan_2012.pdf16. Carvalho PI, Vidal SA, Figueirôa BQ, Vanderlei LCM, Figueiredo JN, Frias PG,

et al. Comitê de mortalidade materna e a vigilância do óbito em Recife no aprimoramento das informações: avaliação ex-ante e ex-post. Rev Bras Saúde Mater Infant. 2023; 23: e20220254.

17. Governo de Pernambuco. Base de Dados do Estado de Pernambuco. Esperança de vida ao nascer -período de referência 1991 a 2010. [

Internet]. [access in 2019 Jul 31]. Available from:

http://www.bde.pe.gov.br/visualizacao/Visualizacao_formato2.aspx?CodInformacao=494&Cod=318. Romeder JM, Mcwhinnie JR. Le développement dês années potentielles de vie perdues comme indicateur de mortalité prématurée. Rev Epidemiol Santé Publique. 1978; 26 (1): 97-115.

19. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Diretoria de Pesquisas, Coordenação de Trabalho e Rendimento. PNAD Contínua - Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua. [

Internet]. [access in 2019 Jul 31]. Available from:

https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/rendimento-despesa-e-consumo/9173-pesquisa-nacional-por-amostra-de-domicilios-continua-trimestral.html?edicao=20653&t=downloads20. Banco Central do Brasil (BCB). Cotações e boletins. [

Internet]. [access in 2019 Jul 31]. Available from:

https://www.bcb.gov.br/estabilidadefinanceira/historicocotacoes21. World Bank. PPP convertion factor. World Bank. Databank. World Devepment Indicator. (Dados do Brasil). [

Internet]. [access in 2019 Jul 31]. Available from:

https://databank.worldbank.org/Exchange-Rate/id/dd21403#22. Maximova K, Rozen S, Springett J, Stachenko S. The use of potential years of life lost for monitoring premature mortality from chronic diseases: Canadian perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2016; 107 (2): e202-4.

23. Fernandes NM, Silva JSGS, Varela DV, Lopes ED, Soares JdJX. The economic impact of premature mortality in Cabo Verde: 2016–2020. PLoS ONE. 2023; 18 (5): e0278590.

24. Kirigia JM, Mwabu GM, Orem JN, Muthuri RDK. Indirect cost of maternal deaths in the WHO African region in 2010. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014; 14 (299): 1-10.

25. GDB 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017; 390: 1151-210.

26. Roldós MI, Corso P, Ingels J. How much are Ecuadorians Willing to Pay to Reduce Maternal Mortality? Results from a Pilot Study on Contingent Valuation. Int J MCH AIDS. 2017; 6 (1): 1-8.

27 White RS, Lui B, Bryant-Huppert J, Chaturvedi R, Hoyler M, Aaronson J. Economic burden of maternal mortality in the USA, 2018-2020. J Comp Eff Res. 2022; 11 (13): 927-33.

28. Melo HP, Morandi L. Measuring unpaid work in Brazil: a methodological proposal. Econ Soc (Campinas). 2021; 30 (71): 187-210.

29. Santos C, Simões A. Estatísticas do uso do tempo: classificações e experiências no Brasil e no mundo. In: Simões A, Athias L, Botelho L (org). Panorama nacional e internacional da produção de indicadores sociais: grupos populacionais específicos e uso do tempo. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, Coordenação de População e Indicadores Sociais; 2018. p.309-41.

Authors' contributionCarvalho PI, Frias PG, Vidal SA, Figueirôa BQ: conception, design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. Assunção RS: design, data analysis and interpretation. Vanderlei LCM, Frutuoso LALM: data analysis and interpretation. All authors approved the final version of the article and declare no conflict of interest.

Data AvailabilityThe entire dataset supporting the results of this study was published in the article itself.

Received on October 8, 2025

Final version presented on October 10, 2025

Approved on October 14, 2025

Associated Editor: Alex Sandro Rolland

; Paulo Germano Frias2

; Paulo Germano Frias2 ; Barbara Queiroz Figueroa3

; Barbara Queiroz Figueroa3 ; Lygia Carmen de Moraes Vanderlei4

; Lygia Carmen de Moraes Vanderlei4 ; Romildo Siqueira Assunção5

; Romildo Siqueira Assunção5 ; Luciana Alves Lima de Melo Frutuoso6

; Luciana Alves Lima de Melo Frutuoso6 ; Suely Arruda Vidal7

; Suely Arruda Vidal7