ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: to analyze the causes of maternal death (MD) and maternal late death (LMD), emphasizing the H1N1 and COVID-19 pandemics.

METHODS: ecological study using data from national mortality and live birth systems. Causes were described according to the WHO Maternal Causes Classification (ICD-MM). Maternal, late, and comprehensive mortality ratios were calculated per 100,000 live births with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

RESULTS: during pandemics, comprehensive mortality was higher: 104.6 (95%CI=95.3;114.5) in 2009-2010 (H1N1), 143.9 (95%CI=132.2;156.2) in 2020-2021 (COVID-19). Between 2020 and 2021, the indicator rose 33.5%. Direct causes predominated except in 2020-2021. The leading direct causes were hypertensive disorders, other obstetric complications, abortion, and hemorrhage. During pandemics, mortality due to hypertensive disorders increased, and among indirect causes, respiratory diseases in 2009-2010 (14.5; 95%CI=11.3-18.5) and other viral infections, mainly coronavirus (55.6; 95%CI=48.5-63.4), in 2020-2021 were prominent.

CONCLUSION: the comprehensive indicator more accurately quantifies the risk of death. Assigning specific causes to late maternal deaths and applying the ICD-MM classification can guide targeted prevention strategies.

Keywords:

Maternal mortality, Cause of death, Influenza A virus, H1N1 subtype, COVID-19, Hypertension

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: analisar as causas de mortalidade materna e materna tardia, com ênfase nas pandemias de H1N1 e COVID-19.

MÉTODOS: estudo ecológico com dados dos sistemas nacionais de informações sobre mortalidade e nascidos vivos. As causas foram descritas segundo a Classificação de Causas Maternas da OMS (ICD-MM). As razões de mortalidade materna, tardia e ampliada foram calculadas por 100.000 nascidos vivos, com intervalos de confiança de 95% (IC).

RESULTADOS: durante as pandemias, a mortalidade ampliada foi mais elevada: 104,6 (IC95%= 95,3-114,5) em 2009-2010 (H1N1) e 143,9 (IC95%=132,2-156,2) em 2020-2021 (COVID-19). Entre 2020 e 2021, o indicador aumentou 33,5%. As causas diretas predominaram, exceto em 2020-2021. As principais causas diretas foram doenças hipertensivas (17,5; IC95%= 13,7–22,1), outras complicações obstétricas, aborto e hemorragia. Durante as pandemias, a mortalidade por doenças hipertensivas aumentou e, entre as causas indiretas, destacaram-se doenças respiratórias em 2009-2010 (14,5; IC95%= 11,3–18,5) e outras doenças virais, principalmente infecção por coronavírus (55,6; IC95%= 48,5–63,4), em 2020–2021.

CONCLUSÃO: o indicador ampliado quantifica de forma mais precisa o risco de morte. A atribuição de causas mais específicas às mortes maternas tardias e a aplicação da CID-MM podem orientar estratégias de prevenção.

Palavras-chave:

Mortalidade materna, Causa de morte, Vírus da influenza A subtipo H1N1, COVID-19, Hipertensão

IntroductionMaternal death is defined as the death of a woman resulting from a condition related to or aggravated by pregnancy, occurring in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle (pregnancy, childbirth, or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy).

1,2For 2020 and 2021, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) per 100,000 live births (LB) in Brazil reached 74.7 and 117.4, respectively. The main causes of death showed little variation, except for COVID-19, which experienced an atypical increase in recent years.

3The leading causes of maternal death are from the direct obstetric group: hemorrhage and hypertensive disorders are the dominant causes, followed by infections, other obstetric causes, and unsafe abortion.

4 There are differences in distribution, and for Latin America and the Caribbean, hypertensive diseases are particularly notable.

4 In Brazil, and especially in the State of Rio de Janeiro, the main direct cause was hypertensive disease of pregnancy.

5,6 In 2012, the World Health Organization developed a classification of causes of maternal death that facilitates the interpretation of mortality statistics and directs prevention measures (WHO ICD-MM).

7Pregnancy can trigger cardiovascular disease, aggravate underlying disease, or cause specific diseases that can manifest from 1 to 3 months after childbirth.

8 Although most maternal deaths occur during the pregnancy-puerperal cycle, the disease burden will be underestimated when only this period is considered, excluding deaths occurring after 42 days that do not make up the maternal mortality ratio indicator.

2,8 Late maternal mortality (LMM) includes obstetric maternal deaths from 43 days to less than one year after childbirth. They are also mostly preventable, and point to the need to extend the follow-up time in the postpartum period, especially for women at higher risk.

8-13 In Brazil, an increasing trend in the LMM ratio was observed from 1999 to 2013, and a mean annual percentage variation of 9.8% from 2010 to 2019.

12 A new indicator – comprehensive maternal deaths – combines maternal deaths and late maternal deaths.

13,14The assignment of O96 code (International Classification of Diseases - ICD-10) as the underlying cause of late maternal death does not clarify whether the causes were direct or indirect, nor does it help define specific preventive actions.

1 Therefore, studying the associated causes of late maternal death (O96) becomes relevant.

There are a few studies on the causes of death associated with late postpartum. In Brazil, in 2002, among the 239 cases of maternal death studied, 13.8% were late deaths (n=33), mainly due to postpartum complications, with emphasis on cardiomyopathy, followed by hypertension complicating pregnancy or hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, and circulatory diseases complicating pregnancy.

2 In other countries, the study of late maternal death causes has made progress.

15-18The pandemics of influenza (H1N1) in 2009 and 2010, and COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) ten years later, impacted the magnitude and distribution of causes of maternal mortality worldwide and in Brazil.

3,19-27 In the USA, 12% of pregnancy-related deaths were attributed to influenza A (H1N1 pdm09) during the 2009–2010 pandemic season, and, among these deaths, 13.7% occurred 42 or more days after delivery.

19 In 2009, the incidence of influenza in Brazil was 28.0/100,000, with a rate of 97/100,000 among pregnant women, and a case-fatality rate of 6.9%.

20 In a Brazilian multicentric study, those who presented severe respiratory disease and tested positive for H1N1 had a worse outcome, with 28.6% dying.

21 As to COVID-19, many studies showed a substantial risk of maternal mortality.

22-27This study analyzed the causes of maternal deaths and the causes associated with late maternal deaths in the State of Rio de Janeiro from 2009 to 2021, with an emphasis on the H1N1 and COVID-19 pandemic periods.

MethodsThis is a descriptive ecological study of maternal mortality, with an emphasis on late mortality and causes of death, among women living in the State of Rio de Janeiro, from 2009 to 2021.

The data sources were the Mortality Information System - State and Federal SIM (Maternal Death Investigation Module) and the Live Birth Information System (Sinasc). The Rio de Janeiro State Health Department provided databases in June 2022.

The causes of maternal death (during pregnancy or up to the 42

nd day after its end) correspond to the codes in chapter XV of the ICD-10, plus codes A34, B20 to B24, D39.2, E23.0, F53, and M83.0 outside chapter XV, when these causes have led to death during the pregnancy-puerperal cycle.

1 Since 2013, the World Health Organization has attributed the code O98.7 to maternal deaths related to HIV/aids. We consider this for the entire analysis period. Deaths due to direct obstetric causes correspond to the ICD 10 codes O00.0 to O08.9, O11 to O23.9, O24.4, O26.0 to O92.7, D39.2, E23.0, F53 and M83.0.), indirect to codes O10.0 to O10.9, O24.0 to O24.3, O24.9, O25, O98.0 to O99.8, A34, B20 to B24), and unspecified to code O95. The underlying cause of late maternal death corresponds to code O96 from chapter XV of ICD-10, without specifying the direct or indirect obstetric causes.

Two authors of this study, who are employees of the State Health Department, have expertise in coding causes of death and reviewing the connections among them. They accessed the Mortality Information System (SIM) and identified late maternal deaths (from 42 to 364 days after the delivery). For each of late maternal deaths, they analyzed all the coded causes declared on parts I and II of the Death Certificate, disregarded the O96 code, and reconstructed the sequence of events leading to death. The automated selection rules of the SIM were applied, which allowed for the assignment of an associated cause of late maternal death as the underlying cause. These selection rules are used in routine analyses by the State Health Department through SIM, helping to reduce the risk of misclassifying the deaths under study. Those deaths for which the associated cause was external (Chapter XX) were excluded from this analysis due to the inability to associate them, either directly or indirectly, with the pregnancy-puerperal cycle. These deaths were classified as "deaths due to external causes occurring in the late postpartum period.

Obstetric causes (chapter XV) of maternal (underlying cause) and late deaths (cause associated with O96, which corresponds to the underlying cause in its absence) were analyzed according to an adapted ICD-MM classification.

6 The ICD-MM classification of maternal death causes groups obstetric causes into direct, indirect, and unknown.

7 The direct causes are grouped into six categories: 1- Abortion (O00-O07), 2- Hypertension (O11-O16), 3- Hemorrhages (O20; O43-O46; O67; O71.0; O71.1, O71.3, O71.4, O71.7; O72), 4- Infections (O23; O41.1; O75.3; O85-O86; O91), 5- Other obstetric complications (O21.1, O21.2; O22; O24.4; O26.6, O26.9; O41.0, O41.8, O71.2, O71.5, O71.6, O71.8, O71.9; O73; O75.0-O75.2, O75.4-O75.9; O87.1, O87.3, O87.9; O88; O90); 6- Unanticipated complications, generally related to anesthetic procedures (O29; O74; O89). The indirect causes are represented by group 7, consisting of all non-obstetric complications (O10; O24.0, O24.2, O24.3, O24.9; O98 [including B20-24, recoded as O98.7], O99), and the unknown causes, group 8, by the ICD O95 code. Group 9, corresponding to causes of death occurred during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period due to external causes (coincident causes) was not analyzed. Mendonça

et al.

6 adapted the original ICD-MM,

7 including the codes O30-O36, O40, O41.9, O42; O60-061 and 063-066 in group 5.

6 Since 2012, the WHO has suggested the use of code O98.7 to classify indirect obstetric maternal deaths from HIV/aids.

7 In Brazil, the SIM began to classify HIV/aids outside Chapter I (B20-B24) as code O98.7 (Chapter XV) from 2020. We adopted the code O98.7 for maternal and late maternal deaths to the entire analysis period.

The absolute and percentage distributions of maternal, late maternal, and comprehensive maternal deaths (sum of the two previous ones) were described. The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and late maternal mortality ratio (LMMR) were calculated accordingly (quotient between maternal and late maternal deaths, respectively, and LB, multiplied by 100,000), and the comprehensive maternal mortality ratio (CMMR) (quotient between the sum of the number of maternal and late maternal deaths and the number of LB, multiplied by 100,000), along with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI95%). Proportional mortality according to the ICD-10 chapter was described for maternal deaths (underlying cause) and late maternal deaths (associated/underlying cause). MMR, LMMR and CMMR were calculated according to the adapted ICD-MM classification (obstetric causes from Chapter XV and main groupings and specific causes up to 4 digits). Relative differences in CMMR between each pandemic period (H1N1 and COVID-19) and the interpandemic period were calculated.

The analyses were conducted annually and, in an aggregated form, in two-year periods during the H1N1 and COVID-19 pandemic years – 2009/10 and 2020/21 – and in order to characterize the pandemic periods (H1N1 and COVID-19) and no pandemic period, the following three-year periods between the two pandemics -2011 to 2013; 2014 to 2016; and 2017 to 2019, as well as the total interpandemic period, from 2011 to 2019.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the

Universidade Federal Fluminense (CAAE: 71323023.0.0000.5243; n

º 6.592.725). The public workers and authors of the study accessed the SIM (Mortality Information System) at the Rio de Janeiro State Health Department, using data not identified by name, preserving privacy and confidentiality.

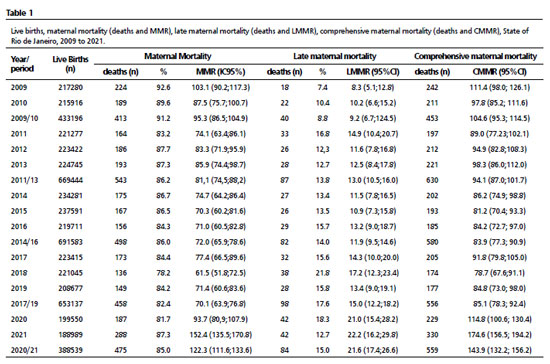

ResultsThere were 2,778 maternal deaths from gestation to 364 days after delivery (comprehensive maternal deaths), in the State of Rio de Janeiro, from 2009 to 2021. The MMR in the H1N1 (2009/2010) and COVID-19 (2020/2021) pandemic years was higher than in the period from 2011 to 2019. LMMR was high in 2011, shortly after the H1N1 pandemic, in the 2017/2019 period (contributing to 17.6% of total deaths), and rose more sharply in the two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. The behavior of the CMMR was strongly influenced by that of the MMR (Table 1). From 2020 to 2021, the CMMR increased by 33.5%, mainly due to maternal deaths, with no overlap between the respective 95% CI. The same behavior is observed by comparing the COVID-19 pandemic CMMR with all other periods, including the H1N1 pandemic. On the other hand, the CMMR in the three-year periods was similar, with the 95%CI overlapping, suggesting stability of the indicator (Table 1).

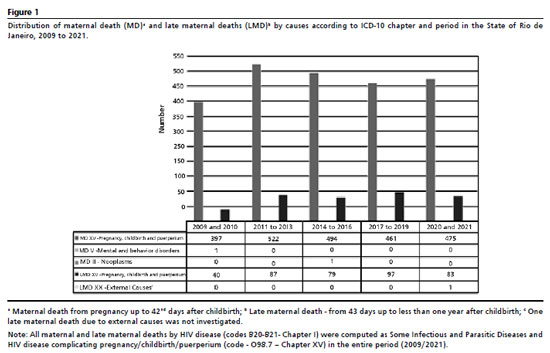

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of maternal and late maternal deaths by cause, according to the ICD chapter. Chapter XV predominated in maternal and late maternal deaths. The non-obstetric causes of maternal death were only one in Chapter II (Neoplasms) and one in Chapter V (Mental and Behavioral Disorders; Nutritional and Metabolic Disorders). For late maternal deaths, outside chapter XV, in the last two years, one death occurred due to external causes.

Considering only Chapter XV and applying ICD-MM classification, all mortality ratios (MMR, LMMR, CMMR) are higher for direct than for indirect causes, except in the final two-year period (COVID-19 pandemic), when this relationship is reversed for MMR, LMMR, and CMMR (Figure 2). Non-specific causes (O95) remained relatively stable, higher in the maternal component from 2011 to 2013. Among the CMMR due to direct causes, hypertensive causes and other obstetric complications stand out, and only from 2017 to 2019 did hemorrhages overtake other obstetric complications, which took third place.

The distribution profile of causes, the main groupings and specific causes (up to 4 digits), and the relative differences of the CMMR are presented for: A) the H1N1 period (2009/10) versus interpandemic period (2011/19), and B) the COVID-19 period versus the interpandemic period (2011/19) (Tables 2 and 3).

Hypertensive causes prevailed among direct obstetric causes, mainly due to gestational hypertension with proteinuria (O14), eclampsia (O15), and unspecified maternal hypertension (O16). In the H1N1 pandemic, the CMMR of the O16 category was higher (2.4 times) than in the inter-pandemic period, and, within the group of obstetric complications, the MMR of uterine contraction abnormalities (O62) was double (Table 2). In the COVID-19 period, the CMMR for severe pre-eclampsia (O14.1) almost doubled (1.8 times) the values of the interpandemic period (Table 2).

Among indirect causes, the H1N1 pandemic, respiratory system diseases (O99.5) predominated, and the respective CMMR was 3.8 times that of the 2011-2019 period (Table 3). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the CMMR for indirect causes nearly doubled compared to the inter-pandemic period. Notably, this relative difference was approximately 160 for other viral diseases (O98.5), including coronavirus infection. (Table 3).

DiscussionThis study, in addition to corroborating the impact of respiratory viruses' pandemics on the magnitude and profile of maternal mortality, highlighted late maternal mortality, which is increasing in the country

12 and the State of Rio de Janeiro, and is also affected by pandemics. The proportional contribution of late deaths reached 17.6% of total deaths in the 2011-2019 period, and there was a rise of LMMR, although less intense than for MMR, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Surveillance and statistical monitoring of late maternal deaths are complex tasks.² In Brazil, the systematic investigation of maternal deaths and deaths of women of reproductive age initiated in 2008, revealed an upward trend in late maternal mortality. This behavior was similar to that observed in European countries with established surveillance systems, such as France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, where late maternal deaths have also shown a growing contribution to overall maternal mortality.¹⁵

,¹⁷

,²⁸

Particularly in the State of Rio de Janeiro, this pattern persisted even when the COVID-19 pandemic years were excluded.

According to Diguisto

et al.,²⁸ among European countries with enhanced maternal mortality surveillance, only France and the United Kingdom routinely include late maternal deaths in their analyses. However, methodological differences across countries persist, largely due to the limited specificity of ICD-MM guidelines for classifying these deaths, reinforcing the need for greater standardization in international comparisons.²⁸

A 2025 study based on Global Burden of Disease estimates for 204 countries showed that, although overall maternal deaths have markedly declined since 1990, the reduction in late maternal deaths has been much smaller, indicating a proportionally greater burden of this component. The analysis also demonstrated an inverse relationship between late maternal deaths and the sociodemographic index (SDI): countries with lower SDI values tend to experience higher rates, but when improvements occur, the decline is proportionally greater. In Brazil, the study identified the State of Rio de Janeiro as having one of the highest national ratios of late maternal deaths, consistent with the findings of the present study.²⁹

Few countries monitor late maternal deaths, according to the Global Burden of Disease study (GBD).

30 The group of experts on maternal mortality of GBD analyzed late maternal death as both a timing category and as a distinct cause because the underlying causes of late maternal deaths are not specified in most data sources. Only a few countries reliably use ICD-10 to code late maternal deaths, despite understanding its significance.

The assignment of an associated cause of late maternal death as the underlying cause, helped to understand this phenomenon and to subsidize health interventions. Direct causes also prevailed among these deaths, except in the COVID-19 years. While hypertensive disorders predominate in maternal deaths, other obstetric complications are more frequent in late maternal deaths, with cardiomyopathy standing out, as in the pioneer study of Laurenti

et al.2 Only in 2020/2021 were hypertensive disorders in the first position for direct late maternal deaths. In Italy, suicide and malignancies are the main causes of late maternal deaths, followed by cardiovascular diseases;

15,17 in the Netherlands, cardiac diseases predominated;

16 and in France and the United Kingdom, cardiovascular disease and suicide.

27 In these European countries, suicide is considered a direct cause of maternal death, being one of the most frequent causes for late maternal deaths. In our study, we excluded external causes associated with late death, which may limit the comparability of results.

As we adopted the code O98.7 to maternal and late maternal death related to HIV/aids, practically all deaths were inside Chapter XV and classified by the ICD-MM.

In the GBD study, AIDS-related deaths were found to commonly occur 42 days or more after the end of pregnancy. Therefore, care efforts for HIV-positive mothers should prioritize ensuring uninterrupted antiretroviral treatment.

29The use of the adapted ICD-MM classification, extended to include late maternal deaths, proved valuable for describing mortality causes over a long observation period. In the United States, applying this classification clarified the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, revealing a notable rise in maternal mortality from both direct and indirect obstetric causes—particularly viral, respiratory, and circulatory diseases—as well as hypertensive disorders.²

² Overall, maternal mortality due to obstetric causes, including late deaths, increased substantially during the pandemic. Similar patterns were observed in our study, where both the H1N1 and COVID-19 pandemics affected maternal and late maternal mortality in comparable ways, consistent with the findings of

Thoma

et al.²³

The changes of maternal deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic may be related directly to viral or respiratory infection by the coronavirus or indirectly by exacerbation of morbid conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases,

23 in addition to worsening of existing care problems, such as difficulty in accessing health services, change in prenatal care services organization, delays in starting prenatal care and in caring for pregnant women with respiratory symptoms.

21-24 The delay in including pregnant and postpartum women in the priority groups for vaccination, as well as the two-month suspension of vaccination in these women with no comorbidities, coincided with the second wave of COVID-19, in which the Gamma variant of SARS-CoV-2 prevailed, with high dissemination, contributing to excess maternal mortality.

24-26 In 2021, the national MMR doubled compared to the previous pandemic year.

3,25The importance of hypertensive disorders as a cause of maternal and late deaths is longstanding, despite improvements in prenatal care and childbirth assistance.

2,6,23 In this study, the CMMR due to hypertensive disorders was among the second and third highest risks of death, with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia being the main causes. Furthermore, hypertensive diseases accounted for half of the late deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in the State of Rio de Janeiro.

This study presents some limitations inherent to the use of secondary data, such as possible inaccuracies in coding and death certificate completion, which may affect the identification of late maternal deaths. Nevertheless, the consistent application of national classification criteria and the reanalysis of cases coded as O96 helped minimize misclassification and strengthen the reliability of the findings.

A major contribution of this study was the reassignment of specific causes to late maternal deaths, qualifying the information traditionally limited by the O96 code. The development and use of a comprehensive maternal mortality indicator, combining deaths occurring during pregnancy and up to one year postpartum, allowed a broader understanding of the maternal health burden and highlighted preventable causes that are often overlooked.

In public health terms, two actions are recommended. First, late maternal deaths should be routinely incorporated into surveillance systems, expanding the scope of existing monitoring frameworks. Second, postpartum care should extend beyond the conventional 42-day period, ensuring clinical follow-up for at least the first three months after delivery, when cardiovascular, hypertensive, and respiratory complications are more frequent. Such measures would enhance prevention and contribute to reducing maternal mortality in Brazil.

References1. Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS). CID-10 Classificação Estatística Internacional de Doenças e Problemas Relacionados à Saúde. 10

a revisão. São Paulo: EDUSP; 1995.

2. Laurenti R, Mello-Jorge MHP, Gotlieb SLD. Maternal deaths and maternal causes. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2008; 17 (4):283-92.

3. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde e Ambiente. Departamento de Análise Epidemiológica e Vigilância de Doenças não Transmissíveis. Mortalidade Materna no Brasil, 2010 a 2021: A Pandemia de Covid-19 e o Distanciamento das Metas Estabelecidas pela Agenda 2030. In: Saúde Brasil 2023: análise da situação de saúde com enfoque nas crianças brasileiras. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2024. Pág.146-75. [

Internet]. [access in 2024 Jul 20]. Available from:

https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/saudebrasil_2023_analise_situacao_criancas.pdf4. Cresswell JA, Alexander M, Chong MYC, Link HM, Pejchinovska M, Gazeley U,

et al. Global and regional causes of maternal deaths 2009-2020: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2025; 13 (4): e626-34.

5. Leal LF, Malta DC, Souza MFM, Vasconcelos AMN, Teixeira RA, Veloso GA,

et al. Maternal Mortality in Brazil, 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2022; 55 (Suppl. 1): e0279.

6. Mendonça I, Silva JBFD, Conceição JFFD, Fonseca SC, Boschi-Pinto C,

et al. Tendência da mortalidade materna no Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, entre 2006 e 2018, segundo a classificação CID-MM. Cad Saúde Pública. 2022; 38 (3): e00195821.

7. World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium: ICD MM. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [

Internet]. [access in 2024 Jul 20]. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892415484588. Sliwa K, Anthony J. Late maternal deaths: a neglected responsibility. Lancet. 2016; 387: 2072-3.

9. Vega CEP, Soares VMN, Nasr AMLF. Late maternal mortality: comparison of two maternal mortality committees in Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2017; 33 (3): e00197315.

10. Carvalho PI, Frias PG, Lemos MLC, Frutuoso LALM, Figuerôa BQ, Pereira CCB,

et al. Sociodemographic and care profile of maternal death in Recife, 2006-2017: descriptive study. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2020; 29 (1): e2019185.

11. Cosio FG, Jiwani SS, Sanhueza A, Soliz PN, Becerra-Posada F, Espinalet MA. Late maternal deaths and deaths from sequelae of obstetric causes in the Americas from 1999 to 2013: a trend analysis. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0160642.

12. Borgonove KCA, Lansky S, Soares VMN, Matozinhos FP, Martins EF, Silva RAR,

et al. Time series analysis: trend in late maternal mortality in Brazil, 2010-2019. Cad Saúde Pública. 2024; 40 (7): e00168223.

13. World Health Organization (WHO). Indicators. The Global Health Observatory. Indicator Metadata Registry List / Maternal Deaths. Geneva: WHO; 2024. [

Internet]. [access in 2024 Jul 20]. Available from:

https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/462214. Cambou MC, David H, Moucheraud C, Nielsen-Saines K, Comulada WS, Macinko J. Time series analysis of comprehensive maternal deaths in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2024; 14 (1): 23960.icd.who.int/en

15. Knight M, Tuffnell D, Kenyon S, Shakespeare J, Gray R, Kurinczuk JJ (Eds.) on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care: Surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2011-13 and lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009-13. Oxford (UK): National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2015. [

Internet]. [access in 2024 Jul 20]. Available from:

https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/MBRRACE-UK%20Maternal%20Report%202015.pdf16. Donati S, Maraschini A, Lega I, D'aloja P, Buoncristiano M, Manno V. Maternal mortality in Italy: Results and perspectives of record-linkage analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018; 97: 1317-24.

17. Kallianidis AF, Schutte JM, Schuringa LEM, Beenakkers ICM, Bloemenkamp KWM, Braams-Lisman BAM,

et al. Confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in the Netherlands, 2006-2018. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022; 101 (4): 441-9.

18. Maraschini A, Mandolini D, Lega I, D'Aloja P, Decenti EC, Baglio G,

et al.; ItOSS Regional Working Group. Maternal mortality in Italy estimated by the Italian Obstetric Surveillance System. Sci Rep. 2024; 14 (1): 31640.

19. Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy-Related Mortality Resulting from Influenza in the United States During the 2009-2010 Pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 126 (3): 486-90.

20. Rossetto EV, Luna EJ. A Descriptive Study of Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 in Brazil, 2009-2010. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2016; 58: 78.

21. Pfitscher LC, Cecatti JG, Pacagnella RC, Haddad SM, Parpinelli MA, Souza JP,

et al.; Brazilian Network for Surveillance of Severe Maternal Morbidity Group. Severe maternal morbidity due to respiratory disease and impact of 2009 H1N1 influenza A pandemic in Brazil: results from a national multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016; 16: 220.

22. Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, Thiruvengadam R, Rauch S, Kholin A,

et al. Maternal and Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality Among Pregnant Women with and Without COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Pediatr. 2021; 175 (8): 1-10.

23. Thoma ME, Declercq ER. All-Cause Maternal Mortality in the US Before vs During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022, 5 (6): e2219133.

24. Guimarães RM, Moreira MR. Maternal deaths as a challenge for obstetric care in times of COVID-19 in Brazil. Rev Bras Saúde Mater Infantil. 2024; 24: e20230078.

25. Scheler CA, Discacciati MG, Vale DB, Lajos GJ, Surita FG, Teixeira JC. Maternal Deaths from COVID-19 in Brazil: Increase during the Second Wave of the Pandemic. Rev Bras Gynecol Obstet. 2022;44 (6): 567-72.

26. Orellana J, Jacques N, Leventhal DGP, Marrero L, Morón-Duarte LS. Excess maternal mortality in Brazil: Regional inequalities and trajectories during the COVID-19 epidemic. PLoS One

2022; 17: e0275333.

27. Brendolim M, Fuller T, Wakimoto M, Rangel L, Rodrigues GM, Rohloff RD,

et al. Severe maternal morbidity and mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cohort study in Rio de Janeiro. IJID Reg. 2023; 6:1-6.

28. Diguisto C, Saucedo M, Kallianidis A, Bloemankamp K, Bodker B, Buoncristiano M,

et al. Maternal Mortality in eight European countries with enhanced surveillance systems: descriptive population-based study. BMJ 2022; 379: e070621.

29. Verma M, Mirza M, Halder P, Gupta M, Rohilla M. Emerging trends in late maternal deaths: Insights from the global burden of disease 2021 estimates. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025 May; 1-11.

30. GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016; 388 (10053): 1775-812.

Authors' contributionBelizzi ALM: Conceptualization (Equal); Formal Analysis (Equal); Investigation (Equal); Methodology (Equal); Project Administration (Equal); Writing original draft (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal).

Kale PL: Conceptualization (Equal); Formal Analysis (Equal); Data curation (Lead); Investigation (Equal); Methodology (Equal); Supervision (Equal); Validation (Equal); Writing original draft (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal).

Fonseca SC: Conceptualization (Equal); Formal Analysis (Equal); Methodology (Equal); Writing original draft (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal).

Cascão AM: Conceptualization (Equal); Formal Analysis (Equal); Data curation (Equal); Investigation (Equal); Methodology (Equal); Supervision (Equal); Validation (Equal); Writing original draft (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal).

All authors approved the final version of the article and declare no conflict of the interest.

Data availabilityAll datasets supporting the result of this study are included in the article.

Received April 14, 2025

Final version presented on September 29, 2025

Approved on October 8, 2025

Associated Editor: Melania Amorim

; Pauline Lorena Kale2

; Pauline Lorena Kale2 ; Sandra Costa Fonseca3

; Sandra Costa Fonseca3 ; Angela Maria Cascão4

; Angela Maria Cascão4