ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: to determine the prevalence of breastfeeding interruption and associated factors in children under two years old living in Pernambuco.

METHODS: cross-sectional study using data from the IV Pesquisa Estadual de Saúde e Nutrição (IV State Health and Nutrition Survey), a household-based survey, carried out in 2015/2016. The information was obtained through standardized forms applied to the children's mothers and/or guardians. In a subsample of 358 children under two years old.

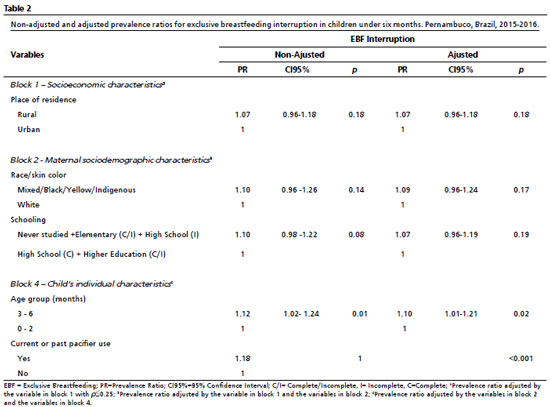

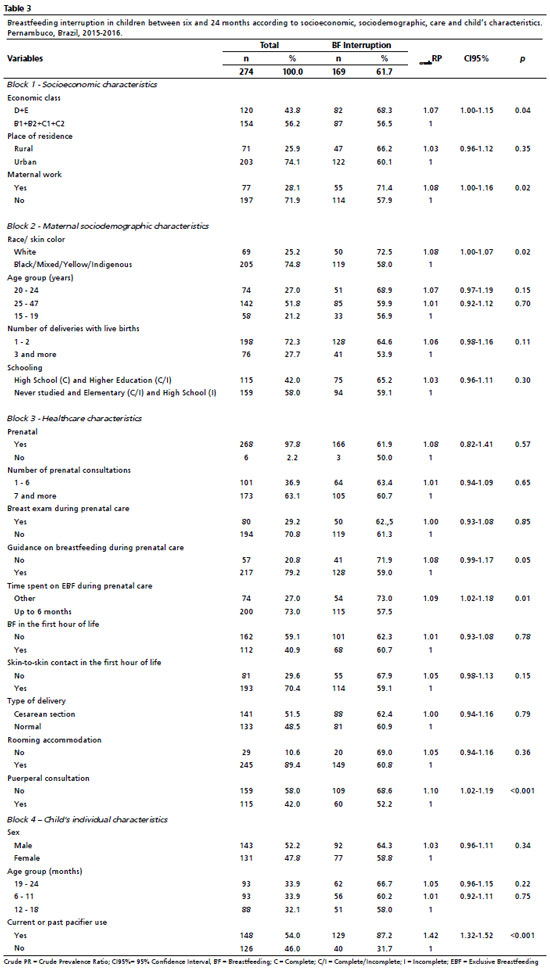

RESULTS: the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) interruption was 76.2% and of breastfeeding 61.7%. In the multivariate regression analysis, the following remained associated with EBF interruption: age range from three to six months (RP= 1.10; CI95%=1.01-1.21) and current or previous use of a pacifier (RP = 1.18; CI95%= 1.07-1.30). For breastfeeding between six and 24 months: economic class D or E (RP=1.08; CI95%=1.01-1.16); maternal work (PR=1.10; CI95%=1.02-1.18); black/mixed color mother (PR=1.07; CI95%=1.00-1.14); not having had a puerperal consultation (PR=1.08; CI95%=1.00-1.16); age group from 19 to 24 months (RP=1.09; CI95%=1.01-1.17) and among those who currently or previously used a pacifier (RP=1.40; CI95%=1.31-1.50).

CONCLUSIONS: the high prevalence of early weaning reveals the need to implement policies to support and encourage breastfeeding, considering the main associated factors.

Keywords:

Infant, Breastfeeding, Prevalence, Risk factors

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: determinar a prevalência da interrupção do aleitamento materno e os fatores associados em menores de dois anos residentes em Pernambuco.

MÉTODOS: estudo transversal utilizando dados da IV Pesquisa Estadual de Saúde e Nutrição, inquérito de base domiciliar, realizada em 2015/2016. As informações foram obtidas através de formulários padronizados aplicados com as mães e/ou responsáveis pelas crianças. Em uma subamostra de 358 menores de dois anos.

RESULTADOS: a prevalência da interrupção do aleitamento materno exclusivo (AME) foi 76,2% e do aleitamento materno 61,7%. Na análise de regressão multivariada permaneceram associados a interrupção do AME: faixa etária de três a seis meses (RP = 1,10; IC95% = 1,01-1,21) e o uso atual ou pregresso de chupeta (RP = 1,18; IC95% = 1,07-1,30). Para o aleitamento materno entre seis e 24 meses: classe econômica D ou E (RP=1,08; IC95%=1,01-1,16); trabalho materno (RP=1,10; IC95%=1,02-1,18); mãe preta/parda (RP=1,07; IC95%=1,00-1,14); não ter realizado consulta puerperal (RP=1,08; IC95%=1,00-1,16); faixa etária de 19 a 24 meses (RP=1,09; IC95%=1,01-1,17) e entre aquelas que faziam uso atual ou pregresso de chupeta (RP=1,40; IC95%=1,31-1,50).

CONCLUSÕES: a alta prevalência do desmame precoce revela a necessidade de implementar políticas de apoio e incentivo ao aleitamento materno considerando os principais fatores associados.

Palavras-chave:

Lactente, Aleitamento materno, Prevalência, Fatores de risco

IntroductionBreastfeeding cessation occurs when a child stops receiving human milk and starts being fed with other liquids or solids, which has health implications throughout life. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), endorsed by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, recommends exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for the first six months of life and continued with complementary food for up to two years or more.

1,2Among the benefits of breastfeeding are in the short or long term, breastfeeding has a positive influence on the mothers and children’s health, regardless of income. EBF protects against diseases, especially diarrhea and pneumonia. In the long term, it is associated with a lower chance of developing obesity, type 2 diabetes, greater intelligence at childhood, adolescence and adulthood and higher levels of formal education and income.

3,4Even if the information on potential breastfeeding is available, it is not easy for women and the family to maintain it as recommended, due to the combination of biological determination and socio-cultural conditioning, economic and political conditioning. Generational knowledge related to breastfeeding and infant feeding, an act that can be regulated by society, was settled and mediated for many years by interests related to behavioral modulation and the chances of making a profit from consumption, through marketing industry, often interposed by health professionals.

4In Brazil, a trend study carried out in four periods (1986, 1996, 2006 and 2013) showed that EBF increased, reaching a prevalence of 37% in 2006 among children under six months of age followed by stabilization in the last period.

5 These changes may be due to the behavioral variables of populations with more vulnerable profiles and who live in regions of lower socioeconomic development. Understanding what causes these changes and the reasons for the interruption may help to maintain the food that has the greatest reduction infant morbidity and mortality.

4,6Considering the relevance of epidemiological in regions with precarious living conditions, which identify the factors associated with the interruption of a universally recommended practice in a period of the children’s lives. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of breastfeeding (BF) interruption and associated factors in children under two years old living in the State of Pernambuco.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional study derived from the IV

Pesquisa Estadual de Saúde e Nutrição (PESN),

7 (IV State Health and Nutrition Survey), a household-based survey on maternal and child health and nutrition carried out in 2015-2016 in Pernambuco.

The PESNs carried out in 1991, 1997, 2006 and 2015-2016 describe the health and nutrition status of the population in Pernambuco. The latest edition had its objectives broadened and was called “

Saúde, alimentação, nutrição, serviços e condições socioeconômicas na população materno-infantil do estado de Pernambuco” (Health, food, nutrition, services and socioeconomic conditions in the maternal and child population of the state of Pernambuco). It covered 13 cities: Recife; Cabo de Santo Agostinho; Jaboatão dos Guararapes; Olinda; Paulista; Belém do São Francisco; Caruaru; Palmares; Panelas; Vicência; São Bento do Una; Serra Talhada and Custódia, statistically representing the rural and urban strata of the population in the State.

The sample selection took place in three stages: the cities were drawn by probability of proportional among the residing population obtained from the Demographic Censuses; the census sectors (sampling units obtained from the

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) in each city were drawn by families with children under the age of five living in each census sector.

The reference sample calculation for the

IV PESN was based on the prevalence of overweight, height deficit, hypovitaminosis A and anemia found in the

III PESN (2006). An estimation error of between 2.4 and 3.8% was taken into account, with an additional 15% to compensate for any losses, at the end, the sample included 875 children under five yeards old. Subsequently, an “ad hoc” database was built with a sub-sample of children under two years of age, used here to investigate breastfeeding interruption.

Data was collected by interviewing children’s mothers and/or guardians, using six standardized forms (F): F1- Household register; F2- Household and income register; F3- Child’s register; F4- Adult’s register; F5- Woman’s register; Family food consumption (qualitative), using the R24h tool (24-hour food recall).

Prior to the beginning of data collection, quality assurance measures were adopted, which involved the use of pre-tested and standardized instruments, based on previous

PESN7; the preparation of a manual with detailed guidelines for conducting the interviews; the training of interviewers and carrying out a pilot study. On this occasion, in addition to testing the instruments, the logistics of the fieldwork were examined in order to check feasibility and make adjustments according to the identified problems.

Based on the bibliographic survey on the subject and the availability of variables in the database, those that constitute potential risk or protective factors for BF were selected. They were then grouped into blocks, forming a hierarchical causal model of the BF interruption (Figure 1). Block 1 includes socioeconomic characteristics (economic class, place of residence and maternal work), while block 2 includes maternal sociodemographic characteristics (race/skin color, age group, schooling, number of deliveries with live births). Block 3 consists of healthcare characteristics (prenatal care, number of prenatal care visits, prenatal breast exam, prenatal breastfeeding guidance, prenatal breastfeeding time, breastfeeding in the first hour of life, skin-to-skin contact in the first hour of life, type of delivery, rooming-in, puerperal visit). Block 4 the child’s individual characteristics (gender, age group, breastfeeding interruption, current or previous use of pacifiers).

The outcomes were breastfeeding interruption among children under six months of age and breastfeeding among children between six and 24 months of age. The former was defined as the situation in which the baby had already received water, tea, juice, other milk, porridge and other food at some point up to the interview or had never been breastfed; and the latter, the situation in which the child was not receiving human milk directly from the breast or drank milk on the day of the interview or had never been breastfed.

Using the SPSS program (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 20, a bivariate analysis of the independent variables with the outcome was carried out using the Prevalence Ratio (PR) and respective 95% confidence intervals (CI95%). Next, a multivariate Poisson regression analysis was carried out with robust adjustment, since these are common outcomes (>10%),

8 adopting a block modeling process as the strategy for introducing the variables, considering the possible factors associated with breastfeeding interruption. The variables selected for inclusion in the model were those with a

p-value≤0.25 in the bivariate analysis.

To estimate the adjusted and unadjusted Prevalence Ratio (PR) and its respective CI95%, the reference category was defined as the one with the lowest risk of breastfeeding interruption, considering

p-values <0.05 to be significant.

The project was submitted to the Human Research Ethics Committee of the

Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira, under CAAE 44508215.7.0000.5201.

ResultsInformation on breastfeeding was obtained from 358 children under the age of two, of whom 84 were under six months and 274 were between six and 24 months old.

Among the children under six months, 64 (76.2%) had interrupted breastfeeding at the time of the interview, 58% were female and aged up to two months. Among the mothers, 75% did not work, 73.8% declared themselves to be black, yellow or indigenous, and 80.6% of these had interrupted breastfeeding. Half were aged between 16 and 24 and 58.3% had up to two living children. In terms of care characteristics, 92.9% of the mothers had prenatal care and 72.6% had received guidance during consultations or group activities. After the birth of the baby, 77 (91.7%) remained in the rooming-in unit at the hospital, 77.9% of whom had interrupted breastfeeding at the time of the interview. In the bivariate analysis, the variables related to care characteristics were not statistically significant; however, the following variables reached a value of

p≤0.25: place of residence; race/skin color and mother’s school; child’s age group and the use of a pacifier (Table 1).

The unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios in the hierarchical multivariate model of the factors associated with interrupted EBF are shown in Table 2. The variables in blocks 1 and 2 in the multivariate analysis lost statistical significance. In block 4, conditions related to the child, the strata with the highest risk for early EBF interruption were: the three to six month age group (PR = 1.10; CI95% = 1.01-1.21) and current or previous used a pacifier (PR = 1.18; CI95% = 1.07-1.30) (Table 2).

Of the universe of children under 24 months, 169 (61.7%) had interrupted breastfeeding at the time of the interview and 52% were male. Among the mothers, 56.2% were from economic class B/C, 28.1% worked, 74% lived in the urban area and self-declared as black, mixed, yellow or indigenous, and 72.3% had up to two children born alive. Among the care characteristics, 20.8% of the women did not receive any guidance on breastfeeding during prenatal consultations or group activities, reaching a higher proportion of weaning (71.9%) when compared to those who received guidance (59.0%). Not having a puerperal visit was identified in 159 (58%) of the mothers, 68.6% of whom interrupted breastfeeding before the child was 24 months old. In the bivariate analysis,

p≤0.25 was obtained for the following variables: economic class, work, mother’s skin color and age group, parity, guidance on EBF, time of EBF guided in prenatal care, skin-to-skin contact in the first hour of life, puerperal appointment, child’s age group and used a pacifier (Table 3).

The unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios in the multivariate model of the factors associated with breastfeeding interruption are shown in Table 4. For the socio-economic block, the strata with the highest probability of interrupting breastfeeding were: belonging to economic classes D and E (PR=1.08; CI95%=1.01-1.16) and maternal work (PR=1.10; CI95%=1.02-1.18); in the socio-demographic block were: mother’s skin color black/mixed or other (PR=1.07; CI95%=1.00-1.14): in the care block: not having a puerperal consultation (PR=1.08; CI95%=1.00-1.16) and in the block related to the child’s individual characteristics, an association was identified with the child’s age 19 to 24 months (PR=1.09; CI95%=1.01-1.17) and among those who currently or previously used a pacifier (PR=1.40; CI95%=1.31-1.50) (Table 4).

DiscussionThe main findings of the study showed that the factors associated with interrupted breastfeeding in children under six months of age were: over three months and current or previous used pacifiers. For breastfeeding in children between six and 24 months, the following factors were associated: economic class D or E, maternal employment, mother’s skin color black, mixed, yellow or indigenous, not having a puerperal appointment, child over 19 months old and current or previous used pacifiers.

Socio-economic characteristics had no influence on EBF, but were associated with BF among those aged between six and 24 months. The likelihood of weaning is shown to be inversely proportional to family income,

9-11 which was confirmed in this study, where the highest likelihood of weaning occurred among children of mothers in economic classes D and E. This association may be due to the difficulty in accessing the media and the internet, which could improve knowledge and information about the importance and benefits of the practice.

12Although this study does not include the type of work women do whether formal or informal, this factor was found to be an obstacle to continuing breastfeeding, corroborating to other studies.

11,13,14 The type of employment influences the duration of breastfeeding; women with informal jobs tend to breastfeed for lesser time because they are not entitled to paid maternity leave. This leave allows the mother to dedicate herself to breastfeeding and caring for the baby during the first few months of life, which is essential for breastfeeding to be continued for two years or more.

15,16The relation among the mother’s race/skin color and the interruption of breastfeeding is controversial in Brazilian studies. The four temporal frames of the Pelotas cohort found that black mothers tended to continue breastfeeding for 12 months or more,

3 similar to that found in the Brazilian macro-regions in 2014.

9 Flores

et al.

10 in 2017 found an inverse association: black mothers were less likely to breastfeed their children for up to two years, similar to our result.

Among the healthcare characteristics, only not having a puerperal visit was associated with abandoning breastfeeding in children under two. The first few days after giving birth are critical for implementing good infant nutritional practices. This is when common problems arise, such as nipple trauma, mastitis, incorrect latch-on and the baby’s difficulty in adapting to life outside the womb. It is also a time when women feel insecure and emotionally fragile.

17,18 The puerperal visit is a moment of care for the mother-baby binomial, in which the support and guidance of a health professional through qualified listening and humanized care helps women to start and continue breastfeeding. At this time, it is possible to identify problems relating to the breastfeeding process, propose interventions that address those particularities, and help with decision-making.

19Among the child’s individual characteristics, those who were older had a higher prevalence of interruption, both for breastfeeding and continued breastfeeding. This finding was consistent with other studies.

20,21 A national survey found that the duration of breastfeeding was inversely proportional to age, with each month of the baby’s life reducing the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding by 33%.

21 These results may be due to mothers’ lack of knowledge about the recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding, the belief that breast milk is not enough as the child grows, leading to the early introduction of water, tea, juice, cow’s milk or infant formula before the sixth month of life.

4,22,23 It may also reflect the lack of support for breastfeeding from partners and co-inhabitants in the household.

In the immediate postpartum period, mothers are usually more dedicated to the baby, and as the weeks go by they take on household chores and caring for older children, reducing the time available for breastfeeding.

21 Some authors report that the impact of the child’s age on breastfeeding may be related to the aggregate effect of other factors such as socioeconomic and demographic factors over time.

4,23The history and/or current use of pacifiers showed a high prevalence and association with the two outcomes of interest and was the factor most strongly associated with the interruption of breastfeeding, increasing the likelihood of the child weaning early by 40%. Its use has been justified as a cultural habit passed down from generation to generation as something positive and characteristic of babies. It is an instrument for comfort, reducing agitation and satisfying the child during breaks from breastfeeding, constituting a maternal aid.

24 Despite cross-sectional studies demonstrating the negative influence on pacifiers on the duration of breastfeeding,

25-27 Recent systematic reviews on the subject have shown conflicting results.

Some authors compared the impact of two forms of using a pacifier over breastfeeding, one restricted, when the pacifier was only used in situations where the baby needed to be soothed, and the other unrestricted, when it was offered for many consecutive hours.It was found that the use of a pacifier had no significant effect on the proportion of babies breastfeeding at three and four months of age.

28 While another meta-analysis of 46 studies found a negative association between pacifier use and breastfeeding. The authors point out that there is heterogeneity in the methods of the articles evaluating the association, making it difficult to elucidate this network of causality.

29The deleterious effects of the use of a pacifier are not restricted to BF. The non-nutritive sucking habit provided by the pacifier impairs the proper development of the entire stomatognathic system. Its use alters oral structures at an early stage, leading to the emergence of occlusal problems, the most common of which are open bite and crossbite, damaging deciduous and mixed dentition.

30This article has some limitations, as the

IV PESN was intended not only to study breastfeeding, but also to include children under two years of age regardless of whether or not they were exposed to the HIV virus, making it impossible to distinguish between exposed and unexposed children; the data collection instrument did not include information on the division of household work and caring for offspring, making it impossible to assess the association between these activities and the time available for breastfeeding; it was also not possible to explore the association between breastfeeding and intimate partner violence due to the unavailability of data in the PESN data. Future state surveys could include variables on these topics in order to better clarify these interactions.

The high prevalence of interrupted breastfeeding reveals the need to implement policies to support and encourage breastfeeding, as well as the importance of population surveys such as the a

Pesquisa Estadual de Saúde e Nutrição (State Health and Nutritional Survey), which allow monitoring of the maternal and child health evolution of.

References1. Leonez DGVR, Melhem ARF, Vieira DG, Mello DF, Saldan PC. Complementary feeding indicators for children aged 6 to 23 months according to breastfeeding status. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2021; 39: e2019408.

2. Pereira TAM, Freire AKG, Gonçalves VSS. Exclusive breastfeeding and underweight in children under six months old monitored in primary health care in Brazil, 2017. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2021; 39: e2019293.

3. Santos IS, Barros FC, Horta BL, Menezes AMB, Bassani D, Tovo-Rodrigues L,

et al. Breastfeeding exclusivity and duration: trends and inequalities in four population-based birth cohorts in Pelotas, Brazil, 1982–2015. Int J Epidemiol. 2019; 48 (1): 72-9.

4. Pérez-Escamilla R, Tomori C, Hernández-Cordero S, Baker P, Barros AJD, Bégin F,

et al. Breastfeeding Series Group. Breastfeeding: crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet. 2023 Feb; 401 (10375): 472-85.

5. Ortelan N, Venancio SI, Benicio MHD. Determinantes do aleitamento materno exclusivo em lactentes menores de seis meses nascidos com baixo peso. Cad Saúde Pública. 2019, 35(8): e00124618.

6. Gonçalves VSS, Silva AS, Andrade RCS, Spaniol AM, Nilson EAF, Moura IF. Marcadores de consumo alimentar e baixo peso em crianças menores de 6 meses acompanhadas no Sistema de Vigilância Alimentar e Nutricional, Brasil, 2015. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2019; 28 (2): e2018358.

7. Lima MR, Caminha MFC, Silva SL, Pereira JCN, Freitas DL,

et al. Evolução temporal da anemia em crianças de seis a 59 meses no estado de Pernambuco, Brasil, 1997 a 2016. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2023; 26: e230023.

8. Vigo Á. Modelando desfechos comuns: viés e precisão. [carta] Cad Saúde Pública. 2006 Nov; 22 (11): 2496-7.

9. Wenzel D, Souza SB. Fatores associados ao aleitamento materno nas diferentes Regiões do Brasil. Rev Bras Matern Infant. 2014, 14 (3): 241-9.

10. Flores TR, Nunes BP, Neves RG, Wend AT, Costa CS, Wehrmeister FC,

et al. Consumo de leite materno e fatores associados em crianças menores de dois anos: Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde, 2013. Cad Saúde Pública. 2017; 33 (11): 1-15.

11. Woldeamanuel BT. Trends and factors associated to early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding and duration of breastfeeding in Ethiopia: evidence from the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Int Breastfeed J. 2020; 15 (3): 1-13.

12. Jama A, Gebreyesu H, Wubayehu T, Gebregyorgis T, Teweldemedhin M, Berhe T,

et al.. Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and its associated factors among children age 6-24 months in Burao district, Somaliland. Int Breastfeed J. 2020; 15 (5): 1-8.

13. Nardi AL, Frankenberg AD, Ranzosi OS, Santo LCE. Impacto dos aspectos institucionais no aleitamento materno em mulheres trabalhadoras: uma revisão sistemática. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2020; 25 (4): 1445-62.

14. Zitkute V, Snieckuviene V, Zakareviciene J, Pestenyte A, Jakaite V, Ramasauskaite D. Reasons for breastfeeding cessation in the first year after childbirth in lithuania: a prospective cohort study. Medicina. 2020; 56 (226): 1-12.

15. Castetbon K, Boudet-Berquier J, Salanave B. Combining breastfeeding and work: findings from the Epifane population-based birth cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20 (10): 1-10.

16. Chen J, Xin T, Gaoshan J, Li Q, Zou K, Tan S,

et al. The association between work related factors and breastfeeding practices among Chinese working mothers: a mixed-method approach. Int Breastfeed J. 2019; 14 (28): 1-13.

17. Chehab RF, Nasreddine L, Zgheib R, Forman MR. Exclusive breastfeeding during the 40-day rest period and at six months in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2020; 15 (45): 1-10.

18. Puharic D, Malicki M, Borovac JA, Sparac V, Poljak B, Araic N,

et al. The effect of a combined intervention on exclusive breastfeeding in primiparas: a randomised controlled trial. Matern Child Nutr. 2020 Jul; 16 (3): e12948.

19. Mcfadden A, Siebelt I, Marshall JL, Gavine A, Lisa-Christine GLC, Symon A,

et al. Counselling interventions to enable women to initiateand continue breastfeeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Breastfeed J. 2019; 14 (42): 1-19.

20. Boccolini CS, Carvalho ML, Oliveira MIC. Fatores associados ao aleitamento materno exclusivo nos primeiros seis meses de vida no Brasil: revisão sistemática. Rev Saúde Pública. 2015; 49 (91): 1-16.

21. Hagos D, Tadesse AW. Prevalence and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding among rural mothers of infants less than six months of age in Southern Nations, Nationalities, Peoples (SNNP) and Tigray regions, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2020; 15 (25): 1-8.

22. Segura-Pérez S, Richter L, Rhodes EC, Hromi-Fiedler A, Vilar-Compte M, Adnew,

et al. Risk factors for self-reported insufficient milk during the first 6 months of life: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2022 May; 18 (Suppl. 3): e13353.

23. Zarshenas M, Zhao Y, Scott JÁ, Binns CW. Determinants of breastfeeding duration in Shiraz, Southwest Iran. Int J Environmal Res Public Health. 2020; 17 (1192): 1-10.

24. Mendes MLM, Gluszevicz AC, Saldanha MD, Costa VPP, Gabatz RIB, Michelon D. A influência da reprodução cultural sobre o hábito de sucção de chupeta. Rev Pesq Qualit. 2019; 7 (13): 89-116.

25. Buccini G, Perez-Escamilla R, Benicio MHA, Giugliani ERJ, Venancio SI. Exclusive breastfeeding changes in Brazil attributable to pacifier use. Plos One. 2018; 13 (12): 1-14.

26. Silva VAAL, Caminha MFC, Silva SL, Serva VMSBD, Azevedo PTACC, Batista-Filho M. Maternal breastfeeding: indicators and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in a subnormal urban cluster assisted by the Family Health Strategy. J. Pediatr. 2019; 95 (3): 298-305.

27. Giugliani ERJ, Nunes LM, Issler RMS, Santo LCE, Oliveira LD. Involvement of maternal grandmother and teenage mother in intervention to reduce pacifier use: a randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr. 2019; 95 (2): 166-72.

28. Jaafar SH, Ho JJ, Jahanfar S, Angolkar M.Effect of restricted pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing duration of breastfeeding (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; 8 (1): 1-25.

29. Buccini GS, Pérez-Escamilla R, Paulino LM, Araújo CL, Venancio SI. Pacifier use and interruption of exclusive breastfeeding: Systematic review and meta - analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2017; 13 (12384): 1-9.

30. Rosa DP, Bonow MLM, Goettems ML, Demarco FF, Santos IS, Matjasevich AB,

et al. The in

fluence of breastfeeding and paci

fier use on the association between preterm birth and primary-dentition malocclusion: A population-based birth cohort study. Am J Orthodont Dentofacial Orthoped. 2020; 157 (6): 754-63.

Authors’ contributionRamalho MOA and Lira PIC: conception of the project, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing and critical revision of the manuscript.Macêdo VC, Frias PG, Oliveira JS: data analysis and interpretation, writing and critical revision of the manuscript.Lima MC: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.Batista Filho M: data analysis and interpretation. All the authors have approved the final version of the article and declare no conflicts of interest.

Received on March 30, 2024

Final version presented on July 30, 2024

Approved on August 13, 2024

Associated Editor: Karla Bomfim

; Vilma Costa de Macêdo 2

; Vilma Costa de Macêdo 2 ; Paulo Germano Frias 3

; Paulo Germano Frias 3 ; Marília de Carvalho Lima 4

; Marília de Carvalho Lima 4 ; Juliana Souza Oliveira 5

; Juliana Souza Oliveira 5 ; Malaquias Batista Filho 6

; Malaquias Batista Filho 6 ; Pedro Israel Cabral Lira 7

; Pedro Israel Cabral Lira 7