ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: to analyze the characteristics and adverse outcomes associated with births that occurred in Indigenous villages in Brazil, using data recorded between 2015 and 2023.

METHODS: this descriptive and ecological study utilized data from the Brazilian Live Birth Information System (Sinasc). We included municipalities with at least one recorded birth in an Indigenous village during the study period. Prevalence Ratios (PR), obtained from robust Poisson regression models, were used to estimate associations between place of birth and adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.

RESULTS: a total of 19,854 births to Indigenous women in villages were recorded. Compared to non-Indigenous mothers, those who delivered in villages had a higher probability of no prenatal care (PR = 7.02; 95%CI= 6.80-7.24), preterm birth (<37 weeks) (PR = 1.70; 95%CI= 1.65-1.75), and low birth weight (<2,500g) (PR = 1.81; 95%CI= 1.75-1.88).

CONCLUSIONS: the findings underscore the magnitude of health inequities affecting Indigenous peoples. The results highlight the need for targeted policies to improve the quality of prenatal and childbirth care. The inclusion of the "Indigenous village" category in the Sinasc presents a critical opportunity for enhanced monitoring and planning of Indigenous health services.

Keywords:

Health information systems, Health inequities, Quality of health care, Indigenous peoples' health

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: analisar a ocorrência de partos realizados em aldeias indígenas segundo características maternas e do recém-nascido registradas ao longo do período 2015-2023.

MÉTODOS: estudo descritivo e ecológico, realizado com base em dados do Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos. Foram selecionados municípios com pelo menos um registro de parto realizado em aldeia indígena no período estudado. As associações entre local do parto e desfechos desfavoráveis foram estimadas por razões de prevalência (RP) com modelos de regressão de Poisson robusta.

RESULTADOS: foram registrados 19.854 partos de mulheres indígenas realizados em aldeias indígenas. Em comparação às mães não indígenas, aquelas que pariram em aldeias apresentaram maior probabilidade de não realizar nenhuma consulta de pré-natal (RP=7,02; IC95%= 6,80–7,24), de parto prematuro (<37 semanas) (RP=1,70; IC95%= 1,65–1,75) e de baixo peso ao nascer (<2.500g) (RP=1,81; IC95%= 1,75–1,88).

CONCLUSÕES: os achados evidenciam a magnitude das iniquidades em saúde que atingem povos indígenas, destacando a necessidade de políticas específicas para a qualificação da atenção pré-natal e ao parto. A inclusão da categoria "aldeia indígena" no Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos abre novas possibilidades de monitoramento e planejamento em saúde indígena.

Palavras-chave:

Sistemas de informação em saúde, Desigualdades em saúde; Qualidade da assistência à saúde; Saúde de populações indígenas

IntroductionIn Brazil, maternal and child health indicators derived from national health information systems have been described based on favorable trends: specifically, increasing rates of positive outcomes (e.g., prenatal care coverage) and decreasing rates of negative ones (e.g., infant mortality).

1,2 Over time, comparisons of maternal and child health across distinct population groups and geographic regions have highlighted numerous situations of health inequity, primarily driven by socioeconomic conditions.

3,4The inclusion of the "color or race" variable in the Live Birth Information System (Sinasc – Portuguese acronym), in the mid-1990s, allowed maternal infant health conditions, in the context of socioeconomic inequities, to be analyzed from an ethnic-racial perspective.

4-8 Over recent years, addressing racial inequities has become a frequent component of public health policy discourse, contributing to the progressive reduction of negative indicators, particularly among Black and Brown mothers and children.

5,8 Notwithstanding, due to methodological particularities, the findings commonly exclude categories as Yellow and Indigenous peoples.

4,8When included in nationally representative analyses, Indigenous mothers and children systematically exhibit health indicators that demonstrate the most significant inequities.

9,10 Comparatively, Indigenous children bear the highest morbidity and mortality rates, including hospitalization for conditions sensitive to primary care and post-neonatal deaths.

9The Indigenous People's Health and Nutrition Survey, conducted in 2010, evidenced shifts in the health profile, with increased prevalence of overweight and hypertension among women and high incidence of morbidities such as pneumonia and diarrhea in children.

11 Despite the high prenatal care coverage, only approximately one third of pregnant Indigenous women initiated follow-up on the first trimester, and the remaining quality indicators fell short of recommendations.

10,11Recently, the Sinasc began incorporating the category "Indigenous village" into the "place of birth" variable, unprecedentedly enabling the analysis of births occurring within this context. Despite the significance of the subject, few studies address the conditions of childbirths occurred in villages, their determinants, and potential outcomes.

10 Analyzing this phenomenon is essential for understanding the geographic, cultural, and institutional barriers that influence access to and the quality childbirth care within Indigenous peoples, as well as for informing public policies that are culturally appropriate and territorially sensitive to the realities of these peoples.

The aim of this study is to analyze the occurrence of childbirths in Indigenous villages using maternal and neonatal characteristics recorded between 2015 and 2023.

MethodsThis was a descriptive, cross-sectional study based on secondary data from Sinasc. The microdata were retrieved from the Sinasc's file transfer platform.

12 In this repository, the Sinasc databases are available for download as electronic files in .dbc format, disaggregated by birth year. For the analyses, we recovered nine electronic files, spanning the period from 2015 to 2023.

In Sinasc, the "place of birth" is recorded using the following categories (a) Hospital, (b) Other health facilities, (c) Home, (d) Others, and (e) Indigenous Village. A new variable was derived by tabulating the mother's color or race categories (White, Black, Yellow, Brown and Indigenous). This variable stratified the maternal population into four groups: (a) Indigenous mother who delivered in villages; (b) Indigenous mothers who delivered at home; (c) Indigenous mothers who delivered in other locations (hospital, other health facilities, etc.), and (d) Non-Indigenous mothers (all other color or race categories grouped).

To standardize comparisons with childbirths of non-Indigenous mothers, the analyses included only municipalities where at least one childbirth in an Indigenous village was recorded between 2015 and 2023 (N=97). Data from the 2022 Demographic Census conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE – Portuguese acronym) were used to calculate the proportion of Indigenous population residing in the selected municipalities (Figure 1).

Maternal sociodemographic characteristics (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) were analyzed with the following highlights: mothers under 20 years of age and those with no formal education (no educational attainment). The pregnancies were classified according to the prenatal care attendance, and neonates were classified by birth weight (being considered of low weight those with less than 2,500 grams) and prematurity (duration of pregnancy <37 weeks).

Cases with missing data for birthplace and mothers' color or race (absent or ignored) were excluded. Comparisons between Indigenous and non-Indigenous mothers were performed by contingency tables and the Chi-square test (

p<0.05).

Associations between birthplace and maternal and neonatal outcomes were estimated using prevalence ratios (PR) and 95%CI, obtained from robust Poisson regression models, with non-Indigenous mothers as the reference group. The choice of robust Poisson regression is justified by the high prevalence of the analyzed outcomes.

13 The analyzes were conducted using SPSS v.23 (IBM

®).

Because this study used publicly available secondary data, it was exempted from Research Ethics Committees approval, as stipulated to CNS Resolution No. 510/2016.

ResultsA total of 915,506 live births were recorded in the 97 selected municipalities between 2015 and 2023. Of these, 19,845 (2.2%) were to Indigenous mothers whose deliveries took place in Indigenous villages, and 92,595 (10.0%) were Indigenous mothers who delivered other locations. Accordingly, births to Indigenous mothers comprised 12.3% of the total births in the analyzed municipalities, with the remainder corresponding to births to non-Indigenous mothers. Furthermore, no "ignored" entries were recorded for the color/race variable among mothers who delivered in Indigenous villages.

According to the 2022 Census, the 97 analyzed municipalities concentrated approximately 31.0% of Brazil's Indigenous population. The majority of these municipalities were situated in the North region (n=78), and in about half of them (N=45), the Indigenous population exceeded 10% of the total inhabitants (Figure 1). While only one live birth to an Indigenous mother in a village was recorded in 16 municipalities during the study period, the municipality of Alto Alegre (Roraima) registered 3,723 such births (an annual average of 414). Overall, more than half of all births in Indigenous villages (10,212; 51.4%) were concentrated in just six municipalities.

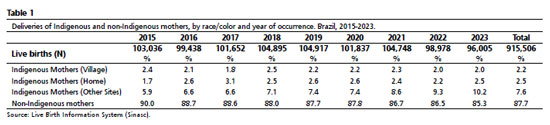

From 2015 to 2023, the proportion of births in Indigenous villages remained stable, ranging from 1.8% (2017) to 2.5% (2018), with an overall average of 2.2% during the period. In contrast, births to Indigenous mothers at home increased from 1.7% to 2.5%. Furthermore, those occurring in other locations (outside villages, hospitals, or other health facilities) nearly doubled, rising from 5.9% to 10.2%. Consequently, the total share of Indigenous births increased from 10.0% in 2015 to 14.7% in 2023, while that of non-Indigenous mothers decreased from 90.0% to 85.3% over the same period (Table 1).

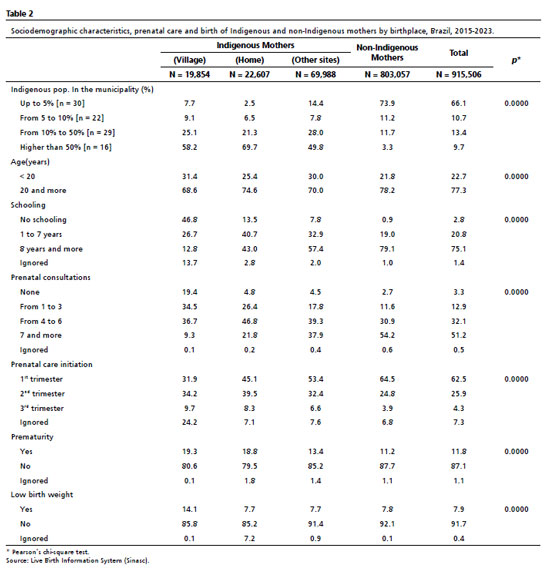

Over half of births to Indigenous mothers (55.3%) occurred in municipalities with a high Indigenous population density (>50%), whereas this percentage was only 3.3% among non-Indigenous mothers. Significant disparities were evident across sociodemographic and healthcare indicators. Regarding educational attainment, 46.8% of Indigenous women who delivered in villages had no formal education, and only 12.8% had 8 or more years of schooling, a sharp contrast to 79.1% among non-Indigenous women. In terms of prenatal care, 19.4% of Indigenous women in villages received no consultations, and only 9.3% achieved seven or more consultations, compared to 54.2% of non-Indigenous mothers. Furthermore, only 31.9% of Indigenous women in villages initiated follow-up during the first trimester, compared with 64.5% of non-Indigenous women. These disparities reverberated in perinatal outcomes: preterm birth was observed in 19.3% of Indigenous women in villages (vs.11.2% in non-Indigenous women), and low birth weight reached 14.1% (vs.7.8%) (Table 2).

The adjusted analyses confirmed significant associations between the place of birth and unfavorable outcomes. Indigenous mothers who delivered in villages exhibited a seven-fold higher prevalence of receiving no prenatal care (PR=7.02; 95%CI=6.80–7.24), in addition to a higher risk of preterm birth (PR=1.70; 95%CI=1.65–1.75) and low birth weight (PR=1.81; 95%CI=1.75–1.88), when compared to non-Indigenous mothers. Differences, albeit of a lesser magnitude, were also found among Indigenous women with home deliveries (no prenatal care PR=1.72; preterm birth PR=1.68) and those who delivered in other locations (no prenatal care PR=1.65; preterm birth PR=1.20) (Table 3).

DiscussionThe key findings of this study, leveraging Sinasc data, demonstrate that deliveries to Indigenous women occurring in villages are associated with substantially higher prevalence ratios of no prenatal care (PR=7.02), preterm birth (PR=1.70), and low birth weight (PR=1.81), compared to non-Indigenous mothers. These effects were more pronounced for village deliveries than for home deliveries or those in other settings, suggesting that the location of birth within a village serves as a powerful marker of inequity in maternal and child healthcare. Besides the disparities in access, these findings point to a mismatch between the prevailing healthcare model and the lifestyles of Indigenous peoples, necessitating culturally sensitive and territorially appropriate approaches.

14It is estimated that approximately two thousand births occur annually in Indigenous villages in Brazil, representing a significant fraction of all births to Indigenous mothers. Such events may simultaneously reflect cultural markers and also serve as an indicator of barriers to accessing health services, which should be considered in the formulation of public policies.

14 This study reveals that these deliveries exhibit a higher prevalence of negative outcomes relative to those of non-Indigenous mothers, particularly among those who received fewer than seven prenatal care consultations or whose children were born with low birth weight.

These results are consistent with with the national literature on health inequities, which associate poorer health indicators with socioeconomic and racial disadvantages, including barriers to access and the quality of prenatal care.

1-4,15 In Indigenous populations, national surveys and analyses point to late initiation of prenatal care, low compliance with recommended procedures, and epidemiological profiles in transition, characterized by the coexistence of infectious diseases and chronic conditions.

10,11 These determinants help to explain the higher frequency of preterm birth and low birth weight observed among neonates born in villages.

Regarding the quality of information, an overall improvement was observed in the completeness of Live Birth Declarations (DNV – Portuguese acronym) throughout the period, consistent with previous studies on Sinasc.

16,17 Nevertheless, an examination of the characteristics related to Indigenous mothers who delivered in villages reveals that the percentage of ignored entries increased considerably over time.

While the percentage of ignored responses for all Indigenous women (deliveries in villages and other settings) was two to three times higher than for non-Indigenous women, the frequency of unreported characteristics among Indigenous women who delivered in villages was four to five times higher than that of non-Indigenous women. These gaps constrain the analysis of steep social gradients and demand continued investment in registry quality improvement. The standardization of instructions for completing "Indigenous village" category is essential to enhance the variable's utility as a surveillance and monitoring tool for equity.

10,16The distribution, which is markedly concentrated in the North Region (>95% of deliveries in villages) reinforces the role of well-documented regional disparities: women from the North Region have a substantially higher probability of inadequate prenatal care compared to women from the South/Southeast Regions.

18 These regional disparities are even more pronounced among Indigenous women residing in Indigenous territories, highlighting the less favorable conditions inherent to the North Region.

The Indigenous People's National Survey of Health and Nutrition (2008-2009) found that, although 90% of Indigenous pregnant women had at least one prenatal visit, only 30% initiated care during the first trimester, with significant gaps in testing and immunization, particularly in the North and Central-West Regions.

10,11Regarding neonatal outcomes, the findings are consistent with the recent decreasing trend of preterm birth in Brazil, though the highest prevalence are found among Indigenous women with no formal education.

19 Low birth weight is also more frequent among Indigenous neonates and is recurrently associated with prematurity, low maternal schooling, and maternal age extremes. Studies in specific contexts, such as that regarding the Guarani population in the South of Brazil, demonstrate the contribution of structural factors such as substandard housing and maternal malnutrition to the occurrence of this outcome.

20,21This study has limitations inherent to the cross-sectional design and the use of secondary data, especially regarding the impossibility of establishing causal relationships between the analyzed variables and the presence of potential biases stemming from coverage and data quality. We highlight the underreporting of deliveries in villages, since Sinasc does not differentiate whether home deliveries occurred within villages, which may underestimate the real magnitude of these events; exploratory estimates suggest that the proportion of deliveries in villages could reach approximately 37.7% under a specific classification scenario.

The absence of specific and clear guidelines for the completion of the "Indigenous village" category in the DNV contributes to inconsistencies and limits variable's utility as a quality surveillance tool.

22,23 Furthermore, the study period spans the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021), which may have affected the access to prenatal care, the care pathways, and the birthplace. Since there was no stratification by subperiods, it is not possible to isolate the effect of this event in the estimates presented.

Another notable finding was the systematic absence of spatial variation in the occurrence of deliveries in Indigenous villages. That is, throughout the study period, the events occurred in the same municipalities, with no records identified in locations where the Indigenous population has a significant presence, such as portions of the Central-West Region.

24 This pattern may indicate both the effective absence of deliveries that occurred in villages in these regions, as well as flaws in the adequate recording of the place of occurrence. These findings are consistent with recent studies that show persistent inequities in maternal and child health among Indigenous peoples in Latin America, including in contexts with specific healthcare subsystems.

25The inclusion of the "Indigenous village" category in the variable that records the birthplace represents a positive strategy, as it allows novel analyses regarding specific conditions of maternal and neonatal care for Indigenous women in their territories. Among the potential applications, sociodemographic information of residents of Indigenous territories may be linked with data from Sinasc, as well as health services' records, particularly the Indigenous Healthcare Subsystem.

In conclusion, the findings of this study demonstrate the persistence of inequities in maternal and neonatal outcomes among Indigenous women who delivered in villages, pointing to structural and institutional barriers to access, as well as limitations in the provision of quality care. We recommend the enhancement of prenatal and birth care for Indigenous women, particularly those who live in villages, with respect sociocultural, regional and territorial specificities; the review and standardization of guidelines for completion of the "Indigenous village" field of the DNV; and the data linkage between Sinasc and the Siasi, to enhance surveillance and inform the planning equity-oriented public policies. The awareness of health professionals and managers for the correct completion of these variables is essential to ensure that data collected reflect the reality experienced in Indigenous territories and contribute to the strengthening of maternal and child health in these contexts.

References1. Victora CG, Aquino EM, Leal MC, Monteiro CA, Barros FC, Szwarcwald CL. Maternal and child health in Brazil: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2011; 377: 1863-76.

2. Vanderlei LCM, Frias PG. Avanços e desafios na saúde materna e infantil no Brasil. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2015; 15(2): 157–8.

3. Rebouças P, Goes E, Pescarini J, Ramos D, Ichihara MY, Sena S,

et al. Ethnoracial inequalities and child mortality in Brazil: a nationwide longitudinal study of 19 million newborn babies. Lancet Global Health. 2022; 10 (10): e1453–62.

4. Santos LKR, Oliveira F, Bastos JL. Iniquidades na assistência pré-natal no Brasil: uma análise interseccional. Physis: Rev Saúde Colet. 2024; 34: e34004.

5. Almeida AHV, Gama SGN, Costa MCO, Viellas EF, Martinelli KG, Leal MC. Economic and racial inequalities in the prenatal care of pregnant teenagers in Brazil, 2011-2012. Rev Bras Saúde Mater Infant. 2019; 19 (1): 43-52.

6. Caldas ADR, Santos RV, Cardoso AM. Iniquidades étnico-raciais na mortalidade infantil: implicações de mudanças do registro de cor/raça nos sistemas nacionais de informação em saúde no Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2022; 38 (4): e00101721.

7. Santana BEF, Andrade ACS, Muraro AP. Tendência da incompletude das variáveis escolaridade e raça/cor da pele da mãe no Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos do Brasil, 2012-2020. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2023; 32: e2022725.

8. Lessa MSA, Nascimento ER, Coelho EAC, Soares IJ, Rodrigues QP, Santos CAST,

et al. Pré-natal da mulher brasileira: desigualdades raciais e suas implicações para o cuidado. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2022; 27(10): 3881-90.

9. Marinho GL, Borges GM, Paz EPA, Santos RV. Mortalidade infantil de indígenas e não indígenas nas microrregiões do Brasil. Rev Bras Enferm. 2019; 2 (1): 57-63.

10. Garnelo L, Horta BL, Escobar AL, Santos RV, Cardoso AM, Welch JR,

et al. Avaliação da atenção pré-natal ofertada às mulheres indígenas no Brasil: achados do Primeiro Inquérito Nacional de Saúde e Nutrição dos Povos Indígenas. Cad Saúde Pública. 2019; 35 (Supl. 3): e00181318.

11. Coimbra CEA, Santos RV, Welch JR, Cardoso AM, Souza MC, Garnelo L,

et al. The First National Survey of Indigenous People's Health and Nutrition in Brazil: rationale, methodology, and overview of results. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13 (1): 52.

12. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Datasus – Transferência de Arquivos [

Internet]. Brasília (DF); [access in 2025 Set 22]. Available from:

https://datasus.saude.gov.br/transferencia-de-arquivos/#13. Amorim LDAF, Oliveira NF, Fiaccone RL. Modelos de Regressão em Epidemiologia. In: Almeida-Filho N, Barreto ML (Org.) Epidemiologia & Saúde: Fundamentos, Métodos, Aplicações. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 2012. p. 252.

14. Garnelo, L, Parente, RCP, Puchiarelli, MLR.

et al. Barriers to access and organization of primary health care services for rural riverside populations in the Amazon. Int J Equity Health. 2020; 19: 54.

15. Mallmann MB, Boing AF, Tomasi YT, Anjos JC, Boing AC. Evolução das desigualdades socioeconômicas na realização de consultas de pré-natal entre parturientes brasileiras: análise do período 2000-2015. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2018; 27: e2018022.

16. Pedraza DF. Qualidade do Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos (Sinasc): análise crítica da literatura. Ciênc saúde coletiva. 2012; 17: 2729–37.

17. Henriques LB, Alves EB, Vieira FMSB, Cardoso BB, D'Angeles ACR, Cruz OG,

et al. Acurácia da determinação da idade gestacional no Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos (SINASC): um estudo de base populacional. Cad Saúde Pública. 2019; 35: e00098918.

18. Wehrmeister FC, Costa JC, Silva LES, Lima NP, Costa FS, Barros AJD. Avaliação das desigualdades na saúde de mulheres e crianças: por quê, como e para quem? Análises do Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos do Brasil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2025; 28: e250029.

19. Martinelli KG, Dias BAS, Leal ML, Belotti L, Garcia ÉM, Santos Neto ET. Prematuridade no Brasil entre 2012 e 2019: dados do Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos. Rev Bras Estud Popul. 2021; 38: e0173.

20. Barreto CTG, Tavares FG, Theme-Filha M, Cardoso AM. Factors Associated with Low Birth Weight in Indigenous Populations: a systematic review of the world literature. Rev Bras Saúde Mater Infant. 2019; 19 (1): 7–23.

21. Barreto CTG, Tavares FG, Theme-Filha M,

et al. Low birthweight, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction: results from the baseline data of the first indigenous birth cohort in Brazil (Guarani Birth Cohort). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20: 748.

22. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise Epidemiológica e Vigilância de Doenças Não Transmissíveis. Declaração de Nascido Vivo: manual de instruções para preenchimento. 4

a ed. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2022. [access in 2024 Out 10]. Available from:

http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/declaracao_nascido_vivo_manual_4ed.pdf23.Santana BEF, Andrade ACS, Muraro AP. Tendência da incompletude das variáveis escolaridade e raça/cor da pele da mãe no Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos do Brasil, 2012-2020. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2023; 32: e2022725.

24. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Demográfico 2022: Indígenas — Primeiros Resultados do Universo. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2023. [access in 2025 Set 23]. Available from:

https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/index.php/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=7310325. Ferreira GAT, Cherchiglia ML, Valk M, Pilecco FB. Mortality trends among Indigenous women of reproductive age in Brazil: a time series analysis. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2025; 48: 101183.

Authors' contributionMarinho GL: conceptualization, project administration, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, manuscript writing and review. Rodrigues AP and Tavares FG: contributed to formal analysis, investigation, manuscript writing and review. All authors approved the final version of the article and declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availabilityAll datasets supporting the study are included in the article.

Received on January 24, 2024

Final version presented on September 24, 2025

Approved on September 25, 2025

Associated Editor: Tatiana Eleuterio

; Andreza Pereira Rodrigues2

; Andreza Pereira Rodrigues2 ; Felipe Guimarães Tavares3

; Felipe Guimarães Tavares3