ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: to understand how parents experience grief after being diagnosed with fetal malformation during the prenatal period.

METHODS: this was a qualitative, exploratory, and descriptive study conducted in the fetal medicine outpatient clinic of a tertiary public hospital in Fortaleza, Ceará. Data were collected between May and July 2019 using semi-structured interviews. Eight subjects participated, six pregnant women and two parents. The material was subjected to categorical content analysis in light of the theoretical model of psychosocial transitions of bereavement in dialogue with perinatal psychology.

RESULTS: after the diagnosis was confirmed, the participants went through different stages of bereavement for the loss of their imaginary baby, which were not shown as linear, but with alternating feelings. Even with the diagnosis of fetal malformation, the parents' emotional attachment to the baby remains present. The main coping strategies reported were religiosity, social and family networks, communication, and mutual support between the couple.

CONCLUSION: the grief at the diagnosis of fetal malformation extends beyond physical loss, encompassing the loss of expectations and the need to redefine the parent's role amidst uncertainties regarding the baby's future. This underscores the importance of incorporating psychological services as an integral part of prenatal care.

Keywords:

Bereavement, Parents, Congenital abnormalities, Prenatal diagnosis

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: compreender a vivência do luto nos pais a partir do diagnóstico de malformação fetal no período pré-natal.

MÉTODOS: pesquisa qualitativa, exploratória e descritiva, realizada no ambulatório de medicina fetal de um hospital público terciário de Fortaleza, Ceará. A coleta foi realizada entre maio e julho de 2019, por meio de entrevistas semiestruturadas. Participaram oito pessoas, sendo seis gestantes e dois pais. O material foi submetido à análise de conteúdo categorial à luz do modelo teórico das transições psicossociais do luto em diálogo com a psicologia perinatal.

RESULTADOS: a partir da confirmação do diagnóstico, os participantes atravessaram momentos distintos das fases do luto pela perda do bebê imaginário, que se mostrou não de forma linear, mas, sobretudo, com alternância de sentimentos. Mesmo com o diagnóstico de malformação fetal, o vínculo afetivo dos pais com o bebê permaneceu presente. A religiosidade, a rede sociofamiliar, a comunicação e o apoio mútuo entre o casal foram as principais estratégias de enfrentamento relatadas.

CONCLUSÃO: o luto diante do diagnóstico de malformação fetal não se limitou à perda física, mas à perda de expectativas e a necessidade de redefinição do papel parental frente às incertezas sobre o futuro do bebê. Reforça-se a importância de se incluir serviços psicológicos como parte do cuidado pré-natal.

Palavras-chave:

Luto, Pais, Anormalidades congênitas, Diagnóstico pré-natal

IntroductionThe process of pregnancy and the result involving parents to prepare for the arrival of the newborn, without any delay, the idealization of a healthy child and a birth without complications. Intrinsic to this period, various feelings are mobilized, such as joy, insecurity and fear of the unknown. In the midst of this, a set of conceptions wrapped in dreams, plans and expectations about the baby is formed in the parents' psyche. Thus, the discovery of a fetal malformation symbolizes, for the parents, the loss of their idealized child.

1Fetal congenital malformations are structural or functional defects of organs, cells or cellular components that arise during the development of the fetus and manifest themselves before birth.

2,3 Any alteration during embryonic development can lead to malformations that vary in their level of impairment, which can have medical, social or aesthetic consequences for the person affected.

3The confirmation of a diagnosis of fetal malformation can trigger thoughts of helplessness and feelings of guilt, anger, frustration, revolte, sadness and anguish, as well as social isolation and negative impacts on self-esteem.

4,5 These reactions can be considered common to any bereavement process, an event which involves a range of biopsychosocial responses expected in a significant loss and which includes, in its elaboration process, the transformation and resignification of the relationship with what was lost.

6 In this sense, the period of adaptation to the diagnosis of fetal malformation reveals itself to the parents as a moment marked by unique and demanding challenges, with diverse repercussions in the emotional, conjugal and family spheres.

7,8It was because the authors of this study worked in a neonatal intensive care unit and were close to the parents' intense experience with their children being hospitalized so early due to prematurity, malformation and the necessity for surgery, that the topic presented here caught their attention. So, in order to improve our understanding of the emotional repercussions caused by the news of a malformation and to broaden our sensitivity to care for these families, we aimed to understand how parents experience grief after being diagnosed with a fetal malformation in the prenatal period.

MethodsThis is a qualitative, exploratory and descriptive study carried out at the fetal medicine outpatient clinic of a tertiary public hospital located in Fortaleza, Ceará, which is a reference in monitoring pregnancies of fetuses diagnosed with congenital anomalies. It should be noted that, although there is a distinction between the terms fetal malformation, congenital anomaly and syndrome in the medical literature, these distinctions were not used in this study.

The data was collected between May and July, 2019, through semi-structured interviews which, in addition to surveying the participants' sociodemographic data, covered topics such as pregnancy planning, the initial reaction to the diagnosis, understanding and feelings about the child's condition, and the parents' feelings for the baby. The interviews were conducted individually in a private room at the clinic and recorded for later transcription.

Participants were recruited by convenience, when pregnant women and their parents were approached while they were waiting for their prenatal appointment and invited to take part in the study according to the following inclusion criteria: having been diagnosed with a fetal malformation during prenatal care for the current pregnancy; being over eighteen years old; allowing the interview to be recorded; having the cognitive ability to answer the proposed instrument. The number of participants was limited by the criterion of theoretical saturation, i.e. when it was found that the information provided was no longer contributed significantly to improve theoretical reflection, the inclusion of new participants was suspended.

9During the collection, although ten interviews were carried out, two pregnant women asked for the recording to be suspended during the procedure. These interviews were then excluded, since the interruption made it impossible to transcribe them in full, compromising the accuracy of the analysis. In the end, only eight participants were considered, six of whom were pregnant women and two fathers, who were partners of the two pregnant women interviewed.

The material obtained from the interviews was examined using content analysis, which is a set of techniques for analyzing communications which, based on systematic and objective methods for describing the content of reports, allows for the inference of knowledge regarding the conditions of production and reception of these messages.

10 The type of content analysis used was categorical. The corpus research was subjected to the three stages proposed by the method (pre-analysis, exploration of the material and analysis of the data acquired) and discussed in the light of the theoretical model of the psychosocial transitions of bereavement

6,11 in the dialogue with the concepts from perinatal psychology.

4,12,13The psychosocial transitions model of bereavement, proposed by Parkes,

6,11 offers a robust framework for understanding bereavement as a dynamic process, characterized by emotional reactions and psychosocial adjustments of the loss. Although initially proposed for the death of a loved one, this model is widely applicable for other forms of losses, such as symbolic or potential loss, represented in this study by the diagnosis of fetal malformation. Parental grief, in this context, can be seen as a response to the loss of expectations and dreams about the child's future.

Parkes

6,11 states that the experience of loss challenges the assumed world, i.e. the individual's internal construction of what we expect from life, from ourselves and from others. In the case of fetal malformation, bereavement involves both the loss of the idealized baby and the necessity to reorganize these personal perspectives in order to incorporate the new reality. In this way, bereavement is not just about the absence of what was lost, but about the reconstruction of a new view of the world.

14In turn, perinatal psychology offers a fundamental approach to understand the emotional bond that parents begin to form with their baby during pregnancy and how this bond is confronted by the diagnosis.

4,12,13 This situation can trigger a significant emotional crisis, affecting parents during pregnancy and possibly in postnatal life, depending on the severity of the malformation.

In this article, excerpts from speeches have been presented to illustrate the findings. In order to maintain anonymity, the participants were identified by letters and numbers in the sequence in which the interviews took place, with the pregnant mothers being identified by the letter "M" and the fathers by the letter "F". It should be emphasized that the parents interviewed were referred to the psychologist linked to the fetal medicine service whenever emotional needs were identified, guaranteeing access to the psychological support.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the hospital under CAAE 11654919.7.0000.5041.

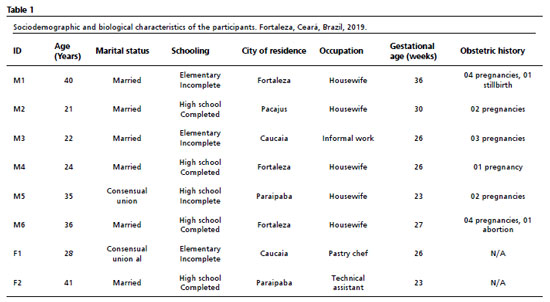

Results and DiscussionRegarding the profile of the interviewees, all lived in the cities in the Metropolitan Region of Fortaleza and were aged between 21 and 41. They were all literate, with high school being the highest level of education. The pregnant women had gestational ages between 23 and 36 weeks. The total number of pregnancies, considering the current one, ranged from one to four. Only one woman had a history of miscarriage and another reported a previous history of stillbirth related to the fetal anomaly. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and biological characteristics of each participant in order to provide a more detailed overview of the people interviewed.

Based on the analysis carried out, three main thematic categories were identified: 1) Imaginary baby and parent-child bond; 2) Grieving process following the diagnosis of fetal malformation; and 3) Coping strategies used by parents. These categories, initially guided by the research's theoretical framework, were refined and enriched by the data emerging from the interviews. Table 2 shows a synoptic table summarizing the thematic categories and the clippings of the most significant statements that represent them, which underpin the subsequent discussions.

Imaginary baby and parent-child bondThe participants' accounts revealed different stories regarding the presence or absence of pregnancy planning and the desire to have a child. Of the eight interviewees, only one said she had planned her pregnancy. Despite this common lack of planning, all of them showed a desire to continue with the pregnancy once they became aware of it. Furthermore, it was possible to identify some of the expectations placed on the figure of the baby and the projects of motherhood and fatherhood, as well as the preparation for the arrival of the child, expressed by planning the trousseau and arranging the child's room.

During the pregnancy period, three gestations co-exist in the parents' psyche: the phantasmatic baby, the imaginary baby and the real baby. The phantasmatic baby is the one present from the beginning of the parents' existence, arising from the primitive experiences of each parent. The imaginary baby represents the set of constructions formed during the mental gestation of the conceptus, and is the result of dreams and desires for motherhood/paternity.

1,15 The formation of the real baby intensifies during the third trimester of pregnancy, as the movement of the fetus increases, signaling its real existence, as well as the use of technologies that allow it to be visualized.

4In this sense, the child begins to exist in the parents' minds long before birth, as long as the parents are able to imagine it. This movement helps form early and fundamental bonds that enable parents to invest in the care and affection of their child from the outset. The desire to know the baby's sex, the choice of name and the physical and behavioral characteristics idealized by the parents are part of the formation of the imaginary baby.

The construction of the imaginary child prepares the parents for the arrival of the real baby.

16 It is through prenatal consultations, heartbeat auscultations and various tests that the information about the development of the fetus is provided to the parents, helping them in the transition to the real baby. The use of imaging technology also makes it possible to make increasingly accurate diagnoses about the existence of any abnormalities during pregnancy, which can lead to a confrontation between the constructed figure of the imaginary baby and the real baby, who is different from the parents' representations.

Each pregnancy has a unique meaning related to the personal history of the pregnant mother and father, the circumstances surrounding this period and the presente support network. These and other factors influence the process of forming the bond, understood as the bond that unites parents and children and can be identified from behavioral, cognitive and affective aspects that indicate attachment, concern and interaction with the fetus, as well as care for the pregnant woman's health.

12,17All the reports collected in this study pointed to the presence of an emotional bond with the baby, with expressions of contentment at the arrival of the new child, even though there was a fetal malformation. These data are in line with the study carried out by Borges and Petean,

17 who identified the persistence of the maternal-fetal bond, even after the diagnosis of congenital malformation. These authors also emphasize the importance of this emotional bond as a facilitator for pregnant women to express better emotional responses to prenatal diagnosis and to cope with the pregnancy.

The grieving process following the diagnosis of a fetal malformation When analyzing the participants' statements, it was observed that the process of parental bereavement in the diagnosis of fetal malformation is permeated by complex emotional dynamics.These dynamics range from initial shock to gradual acceptance and the reorganization of expectations.

Parkes

6 states that bereavement cannot be considered as a state, but rather as a dynamic process, involving not only a set of symptoms that begin with the loss, but also a range of reactions that merge and replace each other. Each stage has its own characteristics, and there are considerable differences in the expressions from one person to the next, both in terms of duration and the way each phase is presented. The author warns that in any grieving process, it is rarely clear exactly what has been lost.

The significant loss dealt with in this research is triggered by the discovery of a fetal malformation, i.e. the loss of the imaginary baby, idealized as healthy and without complications in its development and birth. The emotional, cognitive and behavioral reactions triggered by the diagnosis can be seen in the common phases of: shock and denial of the loss; longing and searching for what has been lost; disorganization and despair, with manifestations of sadness, anger and anxiety; reorganization and recovery, with acceptance of reality, adjustment of expectations and emotional balance, even if the suffering is not completely eliminated.

6,12,14,18,19 These phases can occur at different times during pregnancy and are not necessarily presented in this order.

6,13,18,19In the reports, the manifestation of shock, a phase marked by an abrupt disorder of emotions, accompanied by feelings of helplessness, crying or even the desire to flee,

5,13 emerged shortly after the diagnosis was announced. In this stage, denial can occur in a more subtle way, when parents or the pregnant woman look for other professionals or tests that might contradict the diagnosis, or in a more explicit way, when, despite all the evidence, there is a refusal to broach the subject or the existence of the malformation is ignored.

13In some of the participants' speeches, the presence of feelings of intense sadness, fear, anger and anxiety was noticeable. On the other hand, other accounts were marked by a search for explanations and solutions, as well as a strong desire for the baby's condition to change or improve, even if the diagnosis was irreversible. These expressions gave indications of how the parents were dealing with the diagnosis and going through the grieving process.

With the gradual reduction of anxiety and intense emotional reactions, acceptance and adaptation begin to set in, representing the phase of reorganization and balance.

5,6,13 The feelings of emotional confusion soften and, gradually, the parents feel more comfortable in the situation and begin to believe in their ability to care for the baby.

5,12 In some cases, even though the adaptation process is present, it can be observed in an incomplete way.

At this stage, the baby is seen as a special child. The perception of vulnerability previously experienced is modified by a feeling of growing capacity and coping with the situation.

5 A movement of positive acceptance begins.

12,18 Thus, the pregnant woman or couple begin to form new plans for a reality beyond the baby's malformation and express the experience of an emotional reorganization.

5Studies

12,16 consider that parents need to work through the grief of losing the imaginary baby in order to be able to fully connect with the real baby to come. If the grieving process is fixed in one of the phases, a complicated atmosphere will form within the family, where the ghost of the imaginary healthy baby will become present, tending to interfere with the process of bonding with the real baby. In addition, as a negative consequence, there may also be a deficiency in maternal-fetal health care, manifested through absences from medical appointments, failure to take tests and a lack of self-care on the part of the pregnant woman.

Coping strategies used by parentsFaced with the diagnosis of a fetal malformation, there are elements that interfere with the modulation of the parents' coping and help them, or not, to get through the grieving process. In this study, religiosity, the social and family network, communication and mutual support between the couple were the main factors reported.

For all those interviewed, religiosity was pointed out as an important source of help in the search for balance and in coping with the emotional repercussions of the diagnosis. This finding is in line with studies

5,19,20,21 which have shown that religious practices and spiritual support, because they are linked to feelings of hope and faith,in helping parents to find support in dealing with a situation that requires overcoming, acceptance and decision-making. In addition, despite religiosity being considered a practice with high participation among women, the men in this study also relied on it as a resource of encouragement to cope with the experiences arising from their child's malformation, which is in line with the findings of other studies.

21,22In turn, the socio-family network, seen as those people or systems that are willing to support and reinforce the parents, was also identified as a factor that had an impact on coping with their child's diagnosis.This support can take the form of expressions of affection, encouragement or assistance, helping parents to cope with the situation.

However, sharing information about the fetal malformation is not always a strategy to guarantee support.The bereavement of the imaginary child brings with it a situation of ambiguous loss, the bereavement of the living child, leading to an experience that cannot be openly admitted and which is often not socially validated because it is not recognized.

6,23 In this situation, it is common for parents to encounter expressions of curiosity and uncaring approaches from other family members and acquaintances, which can lead some of them to choose silence as a form of protection.

24Although this choice of silence was present in several speeches during the interviews, it is considered that the search to maintain a social network, as opposed to isolation, can help parents not to remain focused on the diagnosis and to seek healthier ways of dealing with their child's malformation and its consequences. The support network can provide emotional, financial and/or instrumental support (help with housework, for example) which, in cases of high-risk pregnancies, acts as an important protective factor for the mental health of the pregnant woman and the father.

5,20,25In the same way, communication and mutual support between the couple also influenced their approach to coping with the diagnosis. The reports that emerged from the research point to a relationship of partnership and complicity between the couple, which strengthens them to face the situation. On the other hand, it was also observed that there are those who have opted for silence, which can promote distancing within the relationship.

The news of a malformation diagnosis is so traumatizing and destructive that it can have repercussions on the marital relationship, whether it is one of closeness with the establishment of mutual support, or one of distance with the experience of isolation. Klaus

et al.12 use the term asynchronous to describe parents who go through the stages of adaptation at different rates. These parents usually do not talk to each other much about their feelings and can therefore experience difficulties in their relationship. It is as if a temporary emotional separation develops between them, which in some cases can even lead to divorce.

The length of the process of parents adapting to the presence of a child with a malformation will vary from family to family.

18,19 However, in the vast majority of cases it will be a long and painful process, which usually leads to personal growth, changes in personal and spiritual beliefs, as well as parental self-confidence.

12,19Coming into contact with the diagnosis during prenatal care can help form coping strategies in the postpartum period. In this sense, it is recommended

5,8,20 that health professionals offer multidisciplinary support and psychological services as part of prenatal care to help parents cope with this challenging experience, process their emotions and make informed decisions about pregnancy and future care.

This present study provided access to the psychological repercussions caused to the parents by the diagnosis of a fetal malformation, and helped to understand the symbolic aspects brought up by them, thus making it possible to delve into the elements involved in the grieving process. The reflections prompted by the theoretical model

4,6,11,12,13 contributed to reading what was expressed by the parents after the loss of their imaginary baby following the confirmation of a fetal malformation.

One of the limitations of the study was the difficulty in locating other parents during prenatal consultations at the fetal medicine clinic. This resulted in a predominantly female data collection, which was not the initial desire of the research, which sought to include both parents in a more balanced way.

Despite this, by integrating the psychosocial transitions model with concepts from perinatal psychology, a broader understanding of the bereavement experience lived by parents after the diagnosis of a fetal malformation was obtained. This theoretical dialog highlighted the complexity of perinatal bereavement, which was not limited to physical loss, but also involved the loss of expectations and the need to redefine the parental role in the face of uncertainties about the baby's future.

In this way, the information gathered here may prove relevant to professional practice in the fields of fetal medicine, neonatology and perinatal psychology in outpatient and hospital settings. By making it possible to recognize the emotional manifestations that parents go through in this situation, they contribute to welcoming and assisting parents and their families, supporting them in dealing with the grieving process they experience.

References1. Santos S, Ferreira CF, Santos CSS, Nunes MLT, Magalhães AA. A experiência paterna frente ao diagnóstico de malformação fetal. Boletim Acad Paul Psicol. 2018; 38 (94): 87-97.

2. Brito APM, Ribeiro KRA, Duarte VGP, Abreu EP. Enfermagem no contexto familiar na prevenção de anomalias congênitas: revisão integrativa. J Health Biol Sci. 2018; 7 (1): 64-74.

3. Organización Mundial de la Salude (OMS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and Research. Vigilancia de anomalías congénitas: manual para gestores de programas. [

Internet]. Genebra: OMS; 2015. [access in 2024 Jul 11]. Available from:

https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/177241/9789243548722_spa.pdf?sequence=14. Maldonado MT. Psicologia da gravidez: gestando pessoas para uma sociedade melhor. São Paulo: Ideias & Letras; 2017.

5. Gaspar CR. Parents' psychological adaptation after receiving a fetal diagnosis: a systematic review. Grad Student J Psych. 2022; 19.

6. Parkes CM. Luto: estudos sobre a perda na vida adulta. São Paulo: Summus; 1998.

7. Nunes TS, Abrahão AR. Repercussões maternas do diagnóstico pré-natal de anomalia fetal. Acta Paul Enferm. 2016; 29 (5): 565-72.

8. Memo L, Basile E. Pain and grief in the experience of parents of children with a congenital malformation. In: Buonocore G, Bellieni CV, editors. Neonatal pain [Internet]. Cham: Springer; 2017. [access in 2024 Jul 11]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53232-5_22.9. Fontanella BJB, Ricas J, Turato ER. Amostragem por saturação em pesquisas qualitativas em saúde: contribuições teóricas. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008; 24 (1): 17-27.

10. Bardin L. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70; 2011.

11. Parkes CM. Amor e perda: as raízes do luto e suas complicações. São Paulo: Summus; 2009.

12. Klaus MH, Kennell JH, Klaus JH. Vínculo: construindo as bases para um apego seguro e para a independência. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas Sul; 2000.

13. Klaus MH, Kennell JH. Pais/bebê: a formação do apego. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas; 1992.

14. Franco MHP. O luto no século 21: uma compreensão abrangente do fenômeno. São Paulo: Summus; 2021.

15. Guedeney A, Lebovici S. Intervenções psicoterápicas pais/bebê. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 1999.

16. Franco V. Idealização e re-idealização no desenvolvimento dos pais e mães das crianças com deficiência. In: Parlato-Oliveira E, Cohen D, editors. CIEP. São Paulo: Instituto Langage; 2017.

17. Borges MM, Petean EBL. Malformação fetal: enfrentamento materno, apego e indicadores de ansiedade e depressão. Rev SPAGESP. 2018; 19 (2): 137-48.

18. Bianchi B, Spinazola CDC, Galvani MD. Reações da notícia do diagnóstico da síndrome de Down na percepção paterna. Rev Educ Espec. 2021; 34: e16/1-23.

19. Medeiros ACR, Vitorino BLC, Spoladori IC, Maroco JC, Silva VLM, Salles MJS. Sentimento materno ao receber um diagnóstico de malformação congênita. Psicol Estud. 2021; 26: e45012.

20. McCoyd JLM. Critical Aspects of Decision-Making and Grieving After Diagnosis of Fetal Anomaly. In: Paley Galst J, Verp M, editors. Prenatal and Preimplantation Diagnosis [

Internet]. Cham: Springer; 2015. [access in 2024 Jul 11]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18911-6_13.21. Viana ACG, Lopes MEL, Vasconcelos MF, Evangelista CB, Lima DRA, Alves AMPM. Espiritualidade, religiosidade e malformação congênita: uma revisão integrativa de literatura. Rev Enferm UERJ. 2019; 27: 1-9.

22. Vicente SRCRM, Paula KMP, Silva FF, Mancini CN, Muniz SA. Estresse, ansiedade, depressão e enfrentamento materno na anomalia congênita. Estud Psicol. 2016; 21 (2): 104-16.

23. Casellato G. O resgate da empatia: suporte psicológico ao luto não reconhecido. São Paulo: Summus; 2015.

24. Fernandes CR, Martins AC. Vivências e expectativas de gestantes em idade materna avançada com suspeita ou confirmação de malformação. REFACS. 2018; 6 (3): 416-23.

25. Cunha ACB, Marques CD, Lima CP. Rede de apoio e suporte emocional no enfrentamento da diabetes mellitus por gestantes. Mudanças Psicol Saúde. 2017; 25 (2): 35-43.

Authors' contribution: Conceição YZS: Conceptualization, methodology, research, data curation and analysis, writing of the original draft of the text and approval of the final version of the article. Melo EP: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, review and editing of the manuscript, and approval of the final version of the article. All the authors approved the final version of the article and declare no conflict of interest.

Received on July 15, 2024

Final version presented on January 11, 2025

Approved on January 15, 2025

Associated Editor: Aline Brilhante

; Eleonora Pereira Melo2

; Eleonora Pereira Melo2