ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: to estimate the prevalence of manifestations of obstetric violence (OV) perceived by pregnant women during prenatal care and its association with sociodemographic factors.

METHODS: population-based epidemiological, cross-sectional and analytical study conducted with pregnant women assisted in the Family Health Strategy in Montes Claros, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2018/2020. A team of health professionals conducted data collection through face to face interviews. The sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant women and the OV manifestations perceived by pregnant women were assessed. The variables were described by frequency distribution and the prevalence of the types of OV was estimated, with 95% confidence intervals. The Chi-square test was used to evaluate the associations.

RESULTS: the study included 300 pregnant women in their third trimester of pregnancy, most of whom (64.7%) were between 20 and 34 years old, had more than 8 years of schooling (84.5%) and lived with a partner (74.5%). The following prevalences of OV manifestations were estimated in prenatal care: physical (21.7%), sexual (7.0%), psychological (24.3%), and institutional (26.3%). No association was identified between the types of OV and the participants' sociodemographic characteristics.

CONCLUSION: the findings of this study suggest the occurrence of different types of OV in prenatal care in the population investigated and point to the need to improve care practices for pregnant women in Primary Health Care.

Keywords:

Pregnant women, Prenatal care, Primary health care, Obstetric violence

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: estimar a prevalência de manifestações de violência obstétrica (VO) percebidas por gestantes no pré-natal na atenção primária à saúde e sua associação com fatores sociodemográficos.

MÉTODOS: estudo epidemiológico de base populacional, transversal e analítico realizado com gestantes assistidas na Estratégia de Saúde da Família em Montes Claros, Minas Gerais, Brasil, 2018/2020. Avaliaram-se as características sociodemográficas das gestantes e as manifestações de VO percebidas. As variáveis foram descritas por distribuição de frequências e foram estimadas as prevalências dos tipos de VO, com intervalos de 95% de confiança. Adotou-se o teste qui-quadrado para avaliar as associações.

RESULTADOS: participaram do estudo 300 gestantes, no 3º trimestre gestacional, cuja maioria (64,7%) estava na faixa etária de 20 a 34 anos, possuía mais de oito anos de escolaridade (84,5%) e vivia com companheiro (74,5%). Foram estimadas as seguintes prevalências de manifestações de VO no pré-natal: física (21,7%), sexual (7,0%), psicológica (24,3%), e institucional (26,3%). Não foi identificada associação entre os tipos de VO e as características sociodemográficas das participantes.

CONCLUSÃO: os achados desse estudo sugerem a ocorrência dos diferentes tipos de VO na assistência ao pré-natal da população investigada e apontam para a necessidade de aprimoramento das práticas assistenciais às gestantes na Atenção Primária à Saúde.

Palavras-chave:

Gestante, Assistência pré-natal, Atenção primária à saúde, Violência obstétrica

IntroductionObstetric violence (OV) has been recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a public health issue that negatively impacts the health of the woman and her baby.

1 The term “obstetric violence” is used to characterize acts such as mistreatment, disrespect, abuse and neglection during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium.

2 It can be practiced by any professional in the obstetric setting, with abuse of interventions that the physiological, emotional, sexual and cultural aspects of the woman, causing consequences to the maternal and child health.

2 The most common types of OV mentioned in the literature are physical, psychological, sexual and institutional, and can occur during prenatal care, childbirth, puerperium or in cases of abortion.

3 The occurrence of OV is a form of gender-based violence and has been associated with various factors such as parity, history of abortion, type of delivery, marital status, employment status, age, race, socioeconomic and educational level, gender and the professional category of the birth attendant.

4In Brazil, no studies were identified that investigated the occurrence of OV in prenatal care, most of them evaluated the the occurrence of OV during childbirth. Among them, the National Birth in Brazil study

5 found that good practices during labor occurred in less than 50% of women. In the multicenter study

Sentidos do Nascer (Senses of Birth),

6 carried out in five Brazilian cities, OV was reported by 12.6% of women and was associated with lower income, the absence of a partner, delivery in the lithotomy position, the Kristeller maneuver and early separation from the baby after delivery.

The

Estratégia Saúde da Família (ESF) (Family Health Strategy) is the preferred access to the Brazilian health system through prenatal consultations.

7 In

Atenção Primária em Saúde (APS), (Primary Health Care), quality care is recommended for pregnant, parturient and puerperal women is advocated, as standardized by the WHO and the Ministry of Health. Health (MS) with

Programa de Humanização do Pré-natal e Nascimento (PHPN)

8(Prenatal and Birth Humanization Program), the

Rede Cegonha9 (Stork Network) and the

Diretrizes Nacionais de Atenção à Gestante no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS).

10,11(National Guidelines for Pregnant Women’s Care within the Public Health System).

OV occurs when health institutions do not use sufficient human or material resources to guarantee safe care during pregnancy and childbirth. Therefore, it is essential a good clinical and care practice during the pregnancy and puerperal cycle. based on up-to-date scientific evidence and public policies, in order to guarantee respect and necessary humanization for obstetric care.

4,12Considering that OV is a public health issue, with negative impacts on the of women and newborns’ health, and that there is scarce research carried out in Brazil on this topic in the prenatal phase, this study aimed to estimate the prevalence of OV manifestations perceived by pregnant women during prenatal care in APS and its association with sociodemographic factors.

MethodsThis is a population-based, cross-sectional, analytical epidemiological study that used data from a survey entitled “

Estudo ALGE - Avaliação das condições de saúde das gestantes de Montes Claros-MG: estudo longitudinal, da zona urbana do município de Montes Claros, MG, Brasil, in 2018 and 2019.

13,14 (ALGE Study - Evaluation of the health conditions of pregnant women in Montes Claros-MG: a longitudinal study in the urban area of the city of Montes Claros, MG, Brazil)

The “

Estudo ALGE”was carried out in three stages. At baseline, all pregnant women (N=1661) registered with the ESF and who were not pregnant with twins between 2018 and 2019 were included. Pregnant women who were in the first trimester of pregnancy (N= 448) were invited to take part in the second stage of the study when they were in the third trimester of pregnancy and the third stage when they had recently given birth, 40 to 70 days after giving birth. This study refers to the second stage of this cohort.

For the 2nd moment of the “

Estudo ALGE”, the minimum sample size was established considering the following parameters: estimated prevalence of OV in prenatal care of 0.50, 95% confidence level, tolerable error of 5.0%, correction for a finite population (N= 448) and an increase of 20% to compensate for possible non-response and losses. A minimum sample size of 250 pregnant women was estimated. For logistical reasons and access difficulties, it was not possible to include pregnant women living in rural areas.

Prior to data collection, interviewers were trained and a pilot study was carried out with 36 pregnant women registered at one of the ESF units in order to standardize the survey procedures and test the data collection instrument. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews, between October 2018 and November 2019, at the ESF health units or at the homes of the pregnant women, at previously defined times. The interviews were conducted by a team made up of professionals from the fields of nursing, medicine, nutrition, physical education and undergraduate students linked to scientific initiation.

At this stage of the study, the following sociodemographic characteristics of the pregnant women were analyzed: age group (under 20 years old, 20 to 34 years old, over 34 years old), schooling (up to eight years, more than eight years), marital status (with partner, without partner), occupation (formal/informal work, housewife/unemployed), number of children (none, one to two children, more than two children) and family income (below two minimum wages, two or more minimum wages).

In order to analyze the perception of pregnant women regarding the manifestations of OV in prenatal care in APS, an instrument was used, developed by two of the researchers responsible for this study, based on their professional experiences in primary health care and women’s health, as well as on the literature on the subject.

15-17 The instrument consists of ten items structured on a likert scale with five response options: never (0), almost never (1), sometimes (2), almost always (3) and always (4). The items are divided into two domains: objective and subjective aspects of OV. The five items in the objective domain reflect the occurrence of physical or sexual OV, while the five questions in the subjective domain reflect psychological or institutional OV.

The instrument was subjected to content validity, construct validity and reliability analysis. With regard to content validity, which was carried out by fourteen professionals with experience in APS and/or women’s health care, adequate Content Validity Index (CVI)

18 values were observed for the 10 items and the two domains (CVI > 80%). Construct validity was assessed using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The instrument’s two-factor model (domains) had a goodness-of-fit index (GFI) higher than 0.95 and the factor weights of all the items were higher than 0.50 - results considered adequate.

19 As for reliability, estimated by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α), it was found that the two domains and the total scale had values higher than 0.70, which indicates adequate internal consistency.

19All the variables investigated were described using their frequency distributions. The answers to the 10 items of the instrument were dichotomized into the presence or absence of situations that characterize OV. In items 1, 2, 3, 7 and 9, the occurrence of OV was considered when the pregnant woman answered “sometimes, almost always and always”; on the other hand, in questions 4, 5, 6, 8 and 10, the occurrence of OV was considered when the answer was “never, almost never, sometimes”, once the response scale for these items was inverted.

It was estimated the prevalence of the manifestations of the types of OV (physical, psychological, sexual and institutional) during prenatal care, with their respective 95% confidence intervals. For this purpose, the occurrence of a type of OV was considered to be when the pregnant woman perceived it in at least one of the items that reflect each type. In order to assess the association between the types of OV and the sociodemographic variables, the chi-square test was carried out at the 0.05 level.The data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 for Windows

®.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the

Universidade Estadual de Montes Claros through consubstantiated opinions no. 2.483.623/2018 and 3.724.531/2019 of November 25, 2019 (CAAE 80957817.5.0000.5146).

ResultsA total of 300 pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy took part in this stage of the study. The pregnant women’s age ranged from 15 to 46 years, with a mean of 26.5 (±6.4) years. The majority (64.7%) were aged between 20 and 34, had more than eight years of schooling (84.3%) and lived with a partner (74.5%). Up until the date of the interview, 60.4% reported having had six or more prenatal consultations. The other sociodemographic characteristics of the pregnant women are shown in Table 1.

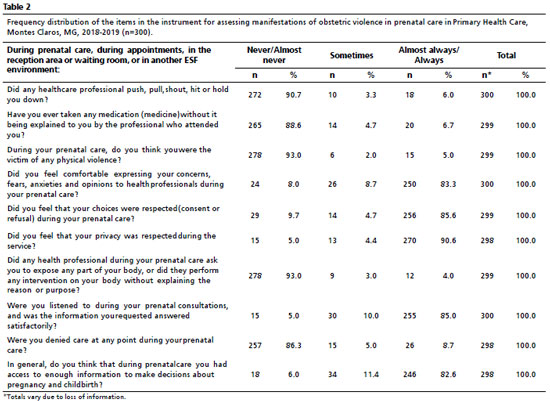

Table 2 shows the frequencies of responses to the items in the instrument that assessed pregnant women’s perception of the occurrence of OV during prenatal care. The frequencies of the “never” and “almost never” response options have been grouped together, as well as the “always” and “almost always” options.

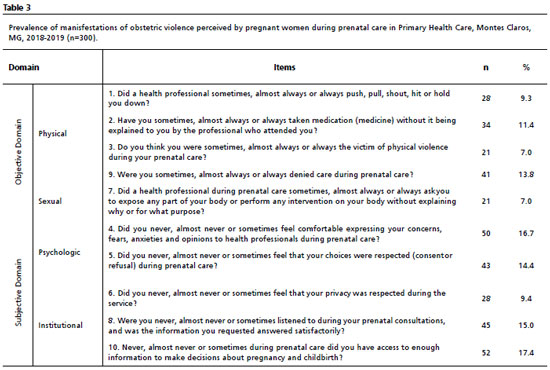

Table 3 shows the prevalence of OV manifestations perceived by the pregnant women, distributed in the objective and subjective domains of the instrument. In the items in the objective domain (1, 2, 3, 7 and 9), the occurrence of OV was considered when the answers were “sometimes, almost always or always”, while in the subjective domain (4, 5, 6, 8 and 10) the perception of OV was considered when the answers were “never, almost never or sometimes”. In the objective domain, items 1, 2, 3 and 9 reflect the occurrence of physical OV, while item 7, the occurrence of sexual OV. In the subjective domain, items 4 and 5 express the perception of psychological OV and items 6, 8 and 9 reflect institutional OV.

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of the types of OV found when the pregnant woman perceived the manifestations that characterize OV in at least one of the items of each type in the questionnaire. The highest prevalences were: institutional OV (26.3%; CI95%=21.6-31.5) and psychological OV (24.3%; CI95%= 19.7-29.4), followed by the prevalence of physical OV (21.7%; CI95%= 17.3-26.6) and sexual OV (7.0%; CI95%=4.5.0-10.35).

Table 4 shows the prevalence of the manifestations of the types of OV perceived by pregnant women during prenatal care, according to sociodemographic characteristics. Although there were no significant associations (

p<0.05), there was a higher prevalence of physical, sexual and psychological OV among pregnant women aged under 20. The results also revealed that the manifestations of the four types of OV were more prevalent among pregnant women who had a higher level of schooling, who were not in the job market and who had more than two children. Women who lived without a partner were more likely to experience physical, psychological and institutional OV. Those with a family income of less than two minimum wages were more likely to experience psychological and institutional OV.

DiscussionSignificant prevalence rates of situations that characterize the occurrence of OV were identified, ranging from 7.0% (sexual OV) to 26.3% (institutional OV).

Given the unavailability of studies dealing with the issue in prenatal care, it was decided to discuss data referring to the hospital environment, recognizing this limitation. Prenatal care can be a tool for preventing obstetric violence during childbirth, when pregnant women are given adequate information and are empowered in their rights.

20 In this sense, its occurrence during prenatal care is doubly damaging to pregnant women.

OV is a significant problem when considering human rights and the fight against gender-based violence, as it specifically targets women and permeates unequal power relations in society.

3 Gender-based violence is a consequence of a social organization, patriarchy, which privileges the male. In the obstetric scenario, this imbalance in power relations between women and health teams is explicit when they abuse interventions that constitute OV.

2,3,5 Women are subjugated in a social context of domination due to their condition that involves harmful gender stereotypes, reinforced by religious, social and cultural beliefs about sexuality, pregnancy and motherhood, where women lose their autonomy and become susceptible to submission by the power relations of patriarchy.

3Although Brazil has rules on the humanization of prenatal care and childbirth,

8,9 there is no specific law in the legal system that criminalizes obstetric violence. Some States and cities have rules to combat obstetric violence, such as Law 23.175/18 in Minas Gerais, which guarantees humanized care for pregnant women, women in labor and women undergoing abortions

21 and Law 23.243/19, which established the “State Week to Combat Obstetric Violence”.

22Physical OV is related to the provocation of pain, discomfort or bodily injury, which causes mild to intense damage, by carrying out procedures without recommendation based on scientific evidence.

3 In this study, it was estimated that 21.7% of women perceived at least one of the situations that characterize the occurrence of physical OV during prenatal care. A study

23 carried out with Mexican pregnant women estimated that 23.6% suffered physical OV and another study

4 in Spain estimated a prevalence of 54.5% of physical OV, both during childbirth. It is important to note that around 13.8% of the pregnant women in this study reported that they had been denied care at some point during prenatal care. The negligence that occurs when care is denied during prenatal care is understood as physical abandonment and lack of care for the patient and her baby.

24In addition, 11.4% of pregnant women reported using medication without the need for it being explained by the professional who assisted them. The use of medication during pregnancy is a public health problem, since the effects of drugs on the fetus can occur at any time during pregnancy.

25 A study in Ceará

26 showed that 38.0% of women did not receive guidance on the use of medication during pregnancy. That is why it is important for women to be aware of the risks and benefits they can have on maternal and child health.

Sexual OV in childbirth has been investigated more frequently in previous studies, while national studies evaluating it during prenatal care are still scarce. Practices carried out inappropriately, which constitute sexual OV, are harmful or ineffective and can begin in health units and maternity wards, including exposure of the woman’s body, without her consent, in the presence of several professionals.

2 Sexual OV involves disrespect for the woman’s intimacy, through unnecessary manipulation of intimate parts through invasive, constant and aggressive vaginal touching, routine episiotomy, enema, imposition of the supine position or lithotomy.

3In this study, 7.0% of the pregnant women said that, during their care with the health professional, they had to expose any part of their body or had interventions made on their body without explaining the reason or purpose. A study carried out in Araguari, Minas Gerais, found that 38.9% of women had suffered sexual OV as a result of painful and repetitive vaginal touching.

26 Another study carried out in the ESF in Rio de Janeiro, RJ, found that 59.0% of women had suffered intimate partner violence, with considerable consequences for their health and use of services.

27Psychological OV encompasses intentional humiliation, mistreatment, negligence in care and rude treatment, disrespect and personal offense.

3 It is characterized by behaviors that generate feelings of vulnerability fear and insecurity.

2 Approximately 24.0% of the participants reported at least one of the episodes of psychological OV evaluated in this study. A study carried out with puerperal women in a city in the Southwest of Bahia

28 found that psychological OV occurred on a smaller scale, with 7.1% suffering personal offense, 7.1% experiencing some embarrassment, 4.8% feeling disrespected and 4.8% being humiliated.

Negative experiences during pregnancy, childbirth or even abortion have numerous psychological, physical and social consequences. According to the WHO, around 10.0% of pregnant women and 13.0% of puerperal women have a mental disorder, and postpartum depression that can affect between 10.0% and 20.0% of puerperal women.

29 Another study

17 showed that 64.0% of the participants did not receive enough prenatal information to feel prepared for childbirth. It is essential that the pregnant woman’s decisions are respected by the ESF team, as the dialog between the multi-professional team and the parturient woman is enlightening and can help guide her towards a quality in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum.

8Institutional OV is related to the asymmetry of power between the patient and the health professional, through the omission of information and/or care, inappropriate or unnecessary conduct, and the imposition of unjustified institutional norms.

3 In this study, 26.3% of pregnant women noticed this type of OV during prenatal consultations, 15.0% of whom were not listened to and informed in a satisfactory manner, and 17.4% who did not receive enough information to actively participate in decisions involving their pregnancy and childbirth. The

Pesquisa Nascer no Brasil,

5 (Birth in Brazil Survey) a large national survey carried out in 2014, estimated that 25.0% of women suffered institutional OV, 74.0% of which occurred in public hospitals, which corroborates the need for health education during prenatal care with a view to preventing such practices.

Resolution 36/2008,

30 which regulates the national operation of obstetric and neonatal care services, guarantees privacy for pregnant women, as the information given by the team of professionals must be transferred safely to the parturient woman. Despite this, around 9.4% of women stated that they never, almost never or sometimes felt that their privacy was respected during care.

This study found no significant association between the types of OV and the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. This finding may be due to the fact that the sample was made up of women with a similar socio-economic profile, in other words, predominantly women with a medium level of schooling, who lived with a partner and had a low family income. Data from the

Pesquisa Nascer no Brasil, show that compared to white women, black puerperal women had a higher risk of inadequate prenatal care, lack of attachment to the maternity hospital, absence of a companion, pilgrimage to the birth and less local anesthesia for episiotomy.

This research has some limitations. An excessively long questionnaire was used to collect data for the “

Estudo ALGE”, which may have caused fatigue and discomfort among the pregnant women. Another limitation is that the instrument used to measure OV was not subjected to concurrent validity, i.e. it was not correlated with another validated instrument measuring the same construct. However, it is worth noting that the instrument showed satisfactory content validity, construct validity and reliability indicators.

During the course of this study, we identified gaps in the epidemiological evidence on prenatal OV, whose research is practically non-existent in the national literature. These gaps make it difficult to update information on the improvement of the

Programa de Humanização no Pré-Natal e Nascimento (PHPN), which outlines the general principles and conditions for adequate prenatal care and adequate childbirth care.

7The concept of obstetric violence as a violation of human rights, as well as its typology that characterizes it in the physical, psychological, sexual and institutional spheres, apply to both prenatal care and care during labour and delivery. For example, the provocation of pain and discomfort, caused by unnecessary touching or lack of privacy, or denial of care. Thus, this study highlights the contributions to the acquisition of new knowledge regarding the epidemiology of OV in prenatal care.

The conclusion is that there was a significant prevalence of OV manifestations perceived during prenatal care in the APS of the city investigated, in terms of physical, psychological, sexual and institutional aspects, regardless of the sociodemographic characteristics of the pregnant women. It is suggested that public policies should be developed to mitigate OV in health institutions, in order to guarantee women care based on scientific evidence, respecting their inherent rights.

References1. Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS). Prevenção e eliminação de abusos, desrespeito e maus-tratos durante o parto em instituições de saúde

. Genebra: Departamento de Saúde Reprodutiva e Pesquisa-OMS; 2014. [access in 2023 Jan 10]. Available from:

https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/134588/WHO_RHR_14.23_por.pdf;sequence=32. Silva JCO, Brito LMC, Alves ES, Medeiros Neto JB, Santos Junior JLP, Marques NM,

et al. Uma revisão sistemática da prevalência e dos tipos da violência obstétrica na saúde e bem-estar das mulheres no Brasil. Res Soc Dev. 2023; 12 (5): e8212541526.

3. Ciello C, Carvalho C, Kondo C, Delage D, Niy D, Werner L,

et al. Violência Obstétrica “Parirás com dor”: Dossiê elaborado pela Rede Parto do Princípio para a CPMI da Violência Contra as Mulheres. Brasília (DF); 2012. [access in 2023 Fev 13]. Available from:

https://www.senado.gov.br/comissoes/documentos/sscepi/doc%20vcm%20367.pdf4. Martínez-Galiano JM, Martinez-Vazquez S, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martinez A. The magnitude of the problem of obstetric violence and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Women Birth. 2021; 34 (5): e526-36.

5. Leite TH, Marques ES, Esteves-Pereira AP, Nucci MF, Portella Y, Leal MDC. Disrespect and abuse, mistreatment and obstetric violence: a challenge for epidemiology and public health in Brazil. Ciên Saúde Colet. 2022; 27 (2): 483-91.

6. Lansky S, Souza KV, Peixoto ERM, Oliveira BJ, Diniz CSG, Vieira NF,

et al. Violência obstétrica: influência da Exposição Sentidos do Nascer na vivência das gestantes. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2019; 24 (8): 2811-23.

7. Macinko J, Mendonça CS. Estratégia Saúde da Família, um forte modelo de Atenção Primária à Saúde que traz resultados. Saúde Debate. 2018; 42 (Spec. 1): 18-37.

8. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Portaria GM/MS nº 569/GM, de 01 de junho de 2000. Programa de Humanização no Pré-natal e Nascimento. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2000. [access in 2023 Fev 13]. Available from:

https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2000/prt0569_01_06_2000_rep.html9. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Portaria Nº 1.459, de 24 de junho de 2011. Institui, no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS - a Rede Cegonha. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2011. [access in 2023 Fev 13]. Available from:

http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2011/prt1459_24_06_2011.html10. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Diretrizes nacionais de atenção à gestante: operação cesariana. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos, Departamento de Gestão e Incorporação de Tecnologias em Saúde. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2016. [access in 2023 Fev 13]. Available from:

https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/pcdt/arquivos/2016/atencao-a-gestante-a-operacao-cesariana-diretriz.pdf/view11. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Diretrizes nacionais de assistência ao parto normal: versão final. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos, Departamento de Gestão e Incorporação de Tecnologias em Saúde. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2017. [access in 2023 Fev 13]. Available from:

https://docs.bvsalud.org/biblioref/2017/06/837345/relatorio_diretrizesnacionais_partonormal_versao-final.pdf12. Garcia LM. A concept analysis of obstetric violence in the United States of America. Nurs Forum. 2020; 55 (4): 654-63.

13. Leão GMMS, Crivellenti LC, Brito MFSF, Silveira MF, Pinho L. Quality of the diet of pregnant women in the scope of Primary Health Care. Rev Nutr. 2022; 35: e210256.

14. Freitas IGC, Lima CA, Santos VM, Silva FT, Rocha JSB, Dias OV,

et al. Nível de atividade física e fatores associados entre gestantes: estudo epidemiológico de base populacional. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2022; 27 (11): 4315-28.

15. Trajano AR, Barreto EA. Violência obstétrica na visão de profissionais de saúde: a questão de gênero como definidora da assistência ao parto. Interface (Botucatu). 2021; 25: e200689.

16. Palma CC, Donelli TMS. Violência obstétrica em mulheres brasileiras. Psico. 2017; 48 (3): 216-30.

17. Teixeira PC, Antunes LS, Duamarde LTL, Velloso V, Faria GPG, Oliveira TS. Percepção das parturientes sobre violência obstétrica: a dor que querem calar. Rev Nurs São Paulo. 2020; 23 (261): 3607-15.

18. Coluci MZO, Alexandre NMC, Milani D. Construção de instrumentos de medida na área da saúde. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2015; 20 (3): 925-36.

19. Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Análise Multivariada de Dados. 6

th ed. Porto Alegre: Bookman; 2015.

20. Lacerda GMO, Mariano VC, Passos SG. Violência Obstétria e os direitos das Gestantes: o que as mulheres sabem?. Rev JRG Estud Acad. 2022; 5 (10): 42-53.

21. Brasil. Lei 23.175/2018. Dispõe sobre a garantia de atendimento humanizado à gestante, à parturiente e à mulher em situação de abortamento, para prevenção da violência na assistência obstétrica no Estado. Governo do Estado de Minas Gerais: Belo Horizonte; 2018. [access in 2023 Mar 10]. Available from:

https://www.legisweb.com.br/legislacao/?id=37284822. Brasil. Lei 23.243/2019

. Institui a Semana Estadual do Combate à Violência Obstétrica a ser realizada, anualmente, de 8 a 14 de março

. Governo do Estado de Minas Gerais: Belo Horizonte; 2018. [access in 2023 Mar 10]. Available from:

https://leisestaduais.com.br/mg/lei-ordinaria-n-23243-2019-minas-gerais-institui-a-semana-estadual-do-combate-a-violencia-obstetrica23. Castro R, Frías SM. Obstetric Violence in Mexico: Results from a 2016 National Household Survey. Violence Against Women. 2019; 26 (6-7): 555-72.

24. Almeida NMO, Ramos BEM. O direito da parturiente ao acompanhante como instrumento de prevenção à violência obstétrica. Cad Ibero-Am Direito Sanit. 2020; 9 (4): 12-27.

25. Aguiar MIB, Alves JMF, Lima JP, Torres KBN. Utilização de medicamentos na gravidez: risco e benefício. Rev Cereus. 2020; 12 (3): 162-74.

26. Carvalho MHJ, Vaz MBS, Silva MAM, Rodrigues MT, Martins NQB, Alamy AHB, Pacheco LM. A violência obstétrica em gestantes, parturientes e puérperas: um estudo de prevalência. Braz J Health Rev. 2021; 4 (6): 26299-320.

27. Esperandio EG, Moura ATMS, Favoreto CAO. Violência íntima: experiências de mulheres na Atenção Primária à Saúde no Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. Interface. 2020; 24 (Suppl. 1): e190707.

28. Rodrigues RL, Merces MC. Prevalência de violência obstétrica em um município do sudoeste da Bahia: um estudo piloto. Enferm Brasil. 2017; 16 (4): 210-7.

29. World Health Organization (WHO). Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan. 2013-2030. [access in 2023 Mar 10]. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924003102930. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução nº 36, de 3 de junho de 2008. Dispõe sobre Regulamento Técnico para Funcionamento dos Serviços de Atenção Obstétrica e Neonatal. [access in 2022 Fev 13]. Available from:

https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2008/res0036_03_06_2008_rep.htmlAuthors’ contributionsFerreira TSB, Lopes BCS, Lima CA and Oliveira AJS: conception and design of the study, data collection, drafting of the manuscript. Pinho L, Brito MFSF and Vogt SE: conception and design of the study, supervision of data collection, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript. Silveira MF: conception and design of the study, statistical analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript.The authors have approved the final version of the article and declare no conflicts of interest.

Received on July 21, 2023

Final version presented on September 4, 2024

Approved on September 5, 2024

Associated Editor: Leila Katz

; Bárbara Cerqueira Santos Lopes 2

; Bárbara Cerqueira Santos Lopes 2 ; Cássio de Almeida Lima 3

; Cássio de Almeida Lima 3 ; Ana Júlia Soares Oliveira 4

; Ana Júlia Soares Oliveira 4 ; Lucineia de Pinho 5

; Lucineia de Pinho 5 ; Maria Fernanda Santos Figueiredo Brito 6

; Maria Fernanda Santos Figueiredo Brito 6 ; Sibylle Emilie Vogt 7

; Sibylle Emilie Vogt 7 ; Marise Fagundes Silveira 8

; Marise Fagundes Silveira 8