ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: bilateral tubal sterilization is a method of contraception, and pregnancy after sterilization is uncommon.

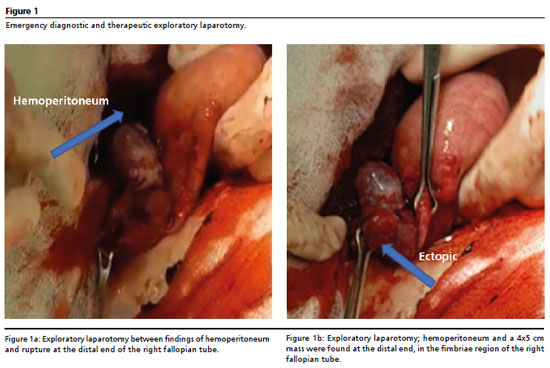

DESCRIPTION: we present the case of a ruptured ectopic pregnancy following postpartum vaginal tubal sterilization. A 33-year-old woman was admitted after presenting lower abdominal pain for 4 days and amenorrhea for 8 weeks, four pregnancies, four vaginal deliveries, and surgical sterilization using the Pomeroy technique performed during her last delivery seven years ago. The patient was β-subunit positive, and a transvaginal ultrasound showed an empty uterus, a heterogeneous mass measuring 55 x 44 mm below the right ovary, and the presence of abundant fluid. Based on the clinical signs, pregnancy test, and imaging, a right ectopic pregnancy was suspected. An exploratory laparotomy was performed, revealing dark clots and blood, a 2500 cc hemoperitoneum, and a 4 x 5 cm mass on the distal stump with active bleeding at the fimbriae.

DISCUSSION: the cause of the ectopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization remains uncertain. The surgical sterilization technique and age at sterilization influence the likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy occurrence.

Keywords:

Ectopic pregnancy, Tubal sterilization, Tubal pregnancy

RESUMO

INTRODUCCIÓN: la esterilización tubárica bilateral es un método de anticoncepción y el embarazo después de la esterilización es poco común.

DESCRIPCIÓN: se presenta el caso de un embarazo ectópico roto después de una esterilización tubárica postparto vaginal. Mujer de 33 años es admitida después de haber presentado dolor abdominal bajo durante 4 días y amenorrea de 8 semanas, cuatro embarazos, cuatro partos vaginales, esterilización quirúrgica según la técnica de Pomeroy realizada durante el último parto, siete años atrás. Subunidad β positiva y la ecografía transvaginal mostró un útero vacío, una masa heterogénea de 55×44 mm por debajo del ovario derecho y presencia de abundante líquido. Sobre la base de los signos clínicos, prueba de embarazo e imágenes, se sospechó un embarazo ectópico derecho. Se realizó una laparotomía exploratoria, encontrándose coágulos oscuros y sangre, un hemoperitoneo de 2500 cc y una tumoración de 4 x 5 cm en muñón distal con sangrado activo a nivel de fimbrias.

DISCUSIÓN: la causa del embarazo ectópico después de la esterilización tubárica sigue siendo incierta, la técnica de la esterilización quirúrgica y la edad en el momento de la esterilización influyen en la probabilidad de que ocurra un embarazo ectópico.

Palavras-chave:

Embarazo ectópico, Esterilización tubária, Embarazo tubárico

IntroductionEctopic pregnancy (EP) is a condition in which a fertilized egg implants outside the endometrial cavity. It has a prevalence of approximately 1.5 to 2.0% among all pregnancies worldwide. A ruptured ectopic pregnancy (EP) is the most feared emergency and represents a significant cause of maternal mortality if not diagnosed and treated immediately.

Bilateral tubal sterilization is a common form of effective permanent contraception preferred by women or couples who have reached their reproductive potential.

1 However, available evidence suggests that sterilization fails in 0.13-1.3% in sterilization procedures, and of these, between 15% and 33% correspond to ectopic pregnancies. Tubal recanalization and the formation of cornual and tuboperitoneal fistulas are the main causes.

According to the

Encueta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar (ENDES) 2024 (Demographic and Family Health Survey), contraceptive use among married women reaches 68.1%, with temporary methods accounting for 56.5% and sterilization as a permanent option in 11.6% of the cases. In the Metropolitan area of Lima, 12.4% of the currently married women use female sterilization, with the highest percentage of having been sterilized between the ages of 30 and 34.

3Ko

et al.

4 reported that pregnancy in the tubal stump after tubal blockage is rare, with a prevalence of around 0.4%. Some pregnancies in the tubal stump occur secondary to tubal ligation.

4Tubal sterilization is highly effective in preventing pregnancy; however, the risk persists for many years after the procedure. Nevertheless, effectiveness may vary depending on the surgical technique used and the patient's age at the time of the procedure, and younger ages are associated with higher rates of contraceptive failure.

2The exact pathogenesis of ectopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization remains unknown. If pregnancy occurs after sterilization, there is a risk of it becoming an ectopic pregnancy;

3 however, it should be suspected of all women of childbearing age with menstrual disorders, pelvic pain, and the presence or absence of adnexal masses.

5There is little evidence of ectopic pregnancy in the distal stump after tubal blockage, after a review of similar cases. In Peru, this is the first case reported in a public hospital with limited resources; therefore, we are interested in sharing our findings on this rare condition. In this report, we present a case of ruptured ectopic pregnancy in the distal stump of the right fallopian tube, following bilateral tubal sterilization by laparotomy after a vaginal delivery.

DescriptionA 33-year-old woman, whose occupation is a cook, was admitted to the emergency room of a public hospital in Lima, Peru, in January 2025, with eight weeks of amenorrhea and four days of lower abdominal pain. She appeared healthy, had no toxic habits, denied any allergies to medications, and had an obstetric history of four pregnancies, four vaginal deliveries, and surgical sterilization using the Pomeroy technique performed during her last delivery seven years ago.

Her blood pressure was 80/40 and her heart rate was 102 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed pallor, hypotension, tachycardia, painful abdomen, and positive rebound tenderness. Gynecological examination reported anteverted uterus, mobile mass in right adnexa painful on mobilization of cervix, no vaginal bleeding. A consultation was performed at the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

Laboratory tests showed a hemoglobin level of 5.6 g/dL, hematocrit of 16.7%, white blood cell count of 5.57 x 10

-3/uL, and platelet count of 153 x 10

-3/uL. She required two units of red blood cells and one unit of plasma prior to surgery. Arterial blood gases were not taken due to a lack of supplies. Serum β-subunit HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) was 539.23 IU/mL.

A transvaginal ultrasound was performed to determine the characteristics of the early pregnancy, revealing an empty uterus with an endometrium of 8 mm and a heterogeneous mass measuring 55×44 mm below the right ovary. No gestational structures were observed within the uterus. Abundant fluid was also observed in the Douglas pouch. The results of these two tests allowed us to determine that it was a ruptured ectopic pregnancy with a sensitivity and specificity of 95 to 100%.

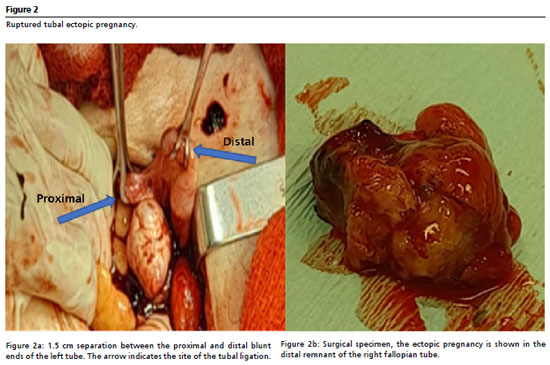

Based on the clinical signs, pregnancy test, and images, a diagnosis of acute surgical abdomen and suspected right ectopic pregnancy was concluded. An emergency diagnostic and therapeutic exploratory laparotomy was performed (laparoscopy could not be performed because the equipment was not available at the time of the surgery). The findings revealed dark clots and blood, a hemoperitoneum of 2500 cc (Figure 1a), a bulging mass approximately 4x5 cm in diameter at the distal end of the remaining portion of the right fallopian tube with active bleeding at the fimbriae (Figure 1b), consistent with a ruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy. A total salpingectomy was performed with removal of the remaining fimbrial end and the ectopic pregnancy. Upon examination of the left adnexa, it was normal; a 1.5 cm separation was observed between the proximal and distal blunt ends of the tube (Figure 2a).

The patient had a favorable postoperative course and was discharged on the third day after the procedure. Her hemoglobin concentration was 8.6 g/dL after three units of packed red blood cells, with follow-up in the outpatient clinic seven days later.

The surgical specimen was sent for pathological examination (Figure 2b). The pathological examination reported a ruptured right tubal pregnancy; presence of syncytiotrophoblast cells and villi, hemorrhage, and blood vessel edema.

This clinical case was approved by the research ethics committee of the

Hospital de Lima Este Vitarte. The patient signed the informed consent form.

DiscussionEctopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization is extremely rare, but not impossible. There is evidence that correctly performed sterilization techniques can result in anatomical tubal patency.

6 However, the persistence of tubal patency does not necessarily imply sterilization failure; tubal patency rates of 1-2% at three months and 16% at five years have been observed after correctly performed tubal ligation, with an actual pregnancy incidence of 1-2% during this period.

6The cause of ectopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization remains unclear. According to the results of the U.S. Collaborative Sterilization Review report, the surgical sterilization technique and the age at the time of sterilization contribute to the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy occurring in ten years.

3 In our case, the patient was 33 years old and underwent bilateral tubal blockage after a vaginal delivery. Chung

et al.,

7 reported that the cumulative rate after ten years was 1.3%, a value two to threefolds higher than that reported by other authors.

7Three mechanisms are considered to be responsible for failures in tubal sterilization: pregnancy in the luteal phase, surgeon error, and failure of the surgical technique. Actual sterilization failures can be considered to be the formation of a uteroperitoneal fistula or spontaneous recanalization.

8 In our case, the proximal and distal parts of the tube were separated due to a Pomeroy-type tubal ligation, and no recanalization of the tubes was evident; the uteroperitoneal fistula could have been the cause of the ectopic pregnancy.

Liang

et al.,

9 reported that possible mechanisms for the development of ectopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization include recanalization of tubal ligation, tubo-peritoneal fistula, or formation of space in the altered tubal lumen.

9 In the case presented, we infer that a microfistula would have formed and, therefore, sperm penetration was possible through the blunt end. As the microfistula was not large enough to allow the passage of the fertilized egg, implantation of the distal segment had occurred. The subsequent rupture caused hemoperitoneum.

Lin

et al.

8 reported a rare case of spontaneous right distal tubal pregnancy after bilateral tubal ligation and deduced that the formation of a microfistula had allowed sperm to penetrate through the blunt end.

8 However, in the present case, stumps of both fallopian tubes were intact, while the distal stump of the right fallopian tube at the level of the fimbriae with a break in continuity, where the ectopic pregnancy developed, was observed.

Liang

et al.

9 highlighted numerous of unusual features of retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy, providing additional evidence to support the main proposed mechanism of embryonic migration through the lymphatic systems by a mechanism similar to lymphatic dissemination in oncological processes.

9Ectopic pregnancy can occur in the proximal or distal remnant of the operated tube. Drakopoulos

et al.

10 described a case in the distal stump after laparoscopic partial isthmic salpingectomy. In the present case, ectopic pregnancy in the distal stump after bilateral sterilization differs from that reported by these authors.

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include pelvic inflammatory disease, previous ectopic pregnancy, multiple sexual partners, history of infertility, assisted reproductive technology, fallopian tube abnormality, and exposure to diethylstilbestrol in utero.

11 The risk factor identified in our case is surgical sterilization using the Pomeroy technique, performed during the last delivery seven years ago.

The clinical characteristics of post-tubal ligation pregnancy include pelvic pain and tubal rupture with hemoperitoneum.

12 These characteristics are consistent with the clinical presentation of our case, which presented with rupture in the distal stump, causing hemoperitoneum with hemodynamic instability and acute surgical abdomen.

With regard to diagnosis, transvaginal ultrasound is the most sensitive method for the early detection of ectopic pregnancy (sensitivity 87-99%). The ultrasound findings showed a right adnexal mass and hemoperitoneum, and the determination of β HCG subunit and clinical manifestations led to the diagnosis of a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy was confirmed intraoperatively, located in the terminal stump of the right tube, and the contralateral tube was thoroughly examined. Finally, the definitive diagnosis was made by the pathological examination of the surgical specimen.

Ectopic pregnancy is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis of acute pelvic pain in patients with a history of tubal sterilization. It is important for patients and treating physicians involved in the care of women of reproductive age to be aware of this complication, as a history of surgical sterilization does not exclude the possibility of ectopic pregnancy, which can occur even several years after the procedure.

2 In the present case, the diagnosis was delayed because the patient did not suspect pregnancy due to the tubal sterilization she had undergone seven years ago. She presented pelvic pain and was taking only symptomatic medication. When she went to the emergency room at the hospital, she was seen by a physician; as the pain did not subside, she was tested for chorionic gonadotropins, which came back positive, and she was referred to gynecology.

The management of ectopic pregnancy can be surgical, medical, or expectant. Management depends on the patient's clinical condition, the location of the ectopic pregnancy, whether it is ruptured or not, and whether the patient desires fertility.

13 The standard treatment for ruptured ectopic pregnancy is surgery via laparoscopy or laparotomy. In our case, we performed a total salpingectomy of the right tube and removal of the ectopic pregnancy by laparotomy, as the center did not have laparoscopic equipment.

Pregnancy rates after laparoscopic and hysteroscopic sterilization are similar (1.8%

vs. 2.0%), with fewer ectopic pregnancies in the first (1.3% vs. 3.9%).

14 The failure rate of the modified Pomeroy technique was 0.4%, and the lowest rates were observed with postpartum ligation and unipolar cauterization (7.5/1000).

5 In general, the incidence of failure varies between 0.13% and 1.3%, and subsequent ectopic pregnancies exceed 10% of the total.

15 Ectopic pregnancy occurs in 1.5–2% of cases and accounts for 6% of maternal deaths; in Peru, its frequency is 2–3%. Mortality attributable to sterilization is low (2–6/100,000), with reduced morbidity linked to anesthetic, infectious, or surgical complications.

5Tubal blockage does not completely rule out ectopic pregnancy, as the stump may remain functional; therefore, complete removal is recommended. We present a rare case of tubal rupture following bilateral sterilization, with health and social implications due to its impact on female reproductive capacity.

References1. Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011-2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug; 130 (2): 366-73.

2. Awonuga AO, Imudia AN, Shavell VI, Berman J, Diamond MP, Puscheck EE. Failed female sterilization: a review of pathogenesis and subsequent contraceptive options. J Reprod Med. 2009 Sep; 54 (9): 541-7.

3. Perú: Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar (Endes 2023) [

Internet]. [access in 2025 Ago 30]. Available from:

https://www.gob.pe/institucion/inei/informes-publicaciones/5601739-peru-encuesta-demografica-y-de-salud-familiar-endes-20234. Ko PC, Liang CC, Lo TS, Huang HY. Seis casos de embarazo tubárico: ¿complicación de la tecnología de reproducción asistida? Fertil Steril. 2011; 95 (7): 2432.

5. Basava L, Roy P, Priya VA, Srirama S. Falope Rings or Modified Pomeroy's Technique for Concurrent Tubal Sterilization. J Obstetr Gynaecol India. 2016 Oct; 66 (Suppl. 1): 198-201.

6. Mills K, Marchand G, Sainz K, Azadi A, Ware K, Vallejo J, et al. Salpingectomy vs tubal ligation for sterilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 2021; 224 (3): 258-65.

7. Chung-Yuan Lee, Ching-Min Lin, Yi-Sin Tan, Che-Min Chen, Hsing-Ju Su, Ling-Yun Cheng,

et al. Subsequent left distal tubal pregnancy following laparoscopic tubal sterilization: a case report. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2022; 49 (6): 132.

8. Lin CM, Ku YL, Cheng YT, Giin NY, Ou YC, Lee MC, et al. An uncommon spontaneous right distal tubal pregnancy post bilateral laparoscopic sterilization: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Jan; 98 (4): e14193.

9. Liang C, Li X, Zhao B, Du Y, Xu S. Demonstration of the route of embryo migration inretroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy using contrast-enhanced computed tomography. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014 Mar; 40 (3): 849-52.

10. Drakopoulos P, Julen O, Petignat P, Dällenbach P. Spontaneous ectopic tubal pregnancy after laparoscopic tubal sterilisation by segmental isthmic partial salpingectomy. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 Mar 22; 2014: bcr2013203131.

11. Tankou CS, Sama CB, Nekame JLG. Occurrence of spontaneous bilateral tubal pregnancy in a low-income setting in rural Cameroon: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Dec; 10 (1): 679.

12. Owiny M, Acen MO, Okeng J, Akello OA. Two Consecutive Ruptured Tubal Ectopic Pregnancies after Interval Bilateral Tubal Ligation. Int Med Case Rep J. 2024 May; 17: 417-21.

13. Eze JN, Obuna JA, Ejikeme BN. Bilateral tubal ectopic pregnancies: a report of two cases. Ann Afr Med. 2012; 11 (2): 112-5.

14. Perkins RB, Morgan JR, Awosogba TP, Ramanadhan S, Paasche-Orlow MK. Gynecologic Outcomes After Hysteroscopic and Laparoscopic Sterilization Procedures. Obstetr Gynecol. 2016; 128 (4): 843-52.

15. Sarella LK. Evaluation of post sterilization ectopic gestations. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar; 6 (4): 1503-6.

Authors' contributionsPantigoso-Gutierrez DF: study design, data collection, data analysis, image design, manuscript writing and revision.

Oscátegui-Peña ME: participated in the conception, data analysis, writing, image design, and manuscript revision.

All authors approved the final version of the article and declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availabilityThe entire dataset supporting the results of this study has been published in the article itself.

Received on June 25, 2025.

Final version presented on September 21, 2025.

Approved on September 24, 2025

Associated Editor: Alex Sandro Souza

; Margarita Eli Oscátegui-Peña2,3

; Margarita Eli Oscátegui-Peña2,3