ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: to develop and validate an educational booklet for pregnant women experiencing pelvic girdle pain.

METHODS: this was a methodological development study conducted at the Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil. The educational booklet was developed following a comprehensive literature review and subsequently validated by healthcare professionals and pregnant women. Content and appearance were assessed using the Content Validity Index (threshold: 0.8 or higher) and the percentage of absolute agreement among participants (threshold: 75% or higher).

RESULTS: in the first stage, healthcare professionals rated the material with a mean global content validity of 0.93. In the second stage, pregnant women indicated an 89.2% agreement regarding its clarity, relevance, and usability. The final version, titled "What You Need to Know About Gestational Pelvic Pain", includes an introduction, the definition and location of pain, its relationship with pregnancy, and practical guidance for prevention and self-management.

CONCLUSION: the educational booklet met the acceptability standards established for validation and may contribute to improving prenatal care and self-management of pelvic girdle pain.

Keywords:

Pregnancy, Health education, Pelvic girdle pain, Physical therapy, Validation study

IntroductionPregnancy is a period characterized by hormonal and biomechanical changes. These physiological alterations, influenced by various factors, can precipitate physical symptoms that may compromise women’s overall quality of life.

1,2 These changes can result in pain, specifically pelvic girdle pain (PGP).

2 Affecting approximately 20% of pregnant women, PGP is precisely defined as pain located between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints. This pain may radiate to the posterior thigh and can occur either in isolation or concurrently with low back pain.

3,4According to the literature, PGP significantly interferes with daily activities, thereby restricting engagement in common tasks such as walking, lifting, bending, driving, cleaning, and cooking.

5,6 Additional consequences include reduced work productivity, diminished sleep quality, and decreased physical energy.

7,8 For a subset of women, persistent pain necessitates medical leave and poses challenges in resuming employment.

7In addition to the physical sequelae, PGP exerts profound psychological and socioeconomic impacts, diminishing quality of life and heightening the susceptibility to anxiety, depression, and pain catastrophizing.

6,9,10 While many women experience spontaneous recovery postpartum, typically within six months, a substantial portion reports significant relief within the first two weeks after childbirth.

11,12 Nevertheless, a distinct subset of women continues to experience PGP long after delivery, with about 8.5% reporting symptoms two years postpartum, an outcome not fully understood in current research.

4 This recovery variability remains elusive, with limited consensus on why some women recover while others do not.

11Given its debilitating nature, high prevalence, and substantial associated costs, PGP constitutes a pressing public health concern.

10 Despite its common occurrence, healthcare-seeking pregnant women frequently encounter insufficient support, which is often attributed to either a lack of professional knowledge or inadequate management options.

13-15 This situation underscores the critical need for accessible interventions to alleviate PGP, thereby highlighting the need for effective strategies that are amenable to broad implementation.

Current treatment options encompass pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches, such as physical exercises, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and acupuncture.

16 However, these methods present inherent limitations: pharmacological interventions carry risks if misused by pregnant women; non-pharmacological treatments, such as TENS, exhibit limited supportive evidence for this specific population; and physical exercises may lose effectiveness when adherence decreases.

16,17Consequently, it is imperative to develop resources that empower pregnant women to self-manage their condition, thus fostering independence via a cost-effective approach. Evidence suggests that self-management materials, particularly when tailored to the target population, with accessible language, clear content, and engaging visuals, can effectively enhance adherence and promote meaningful health outcomes.

18 The quality and reliability of the information provided are paramount, as these attributes facilitate comprehension and, subsequently, symptom improvement.

19Educational booklets constitute powerful instruments in health education, promoting awareness and fostering autonomy and self-care without reliance on pharmacological interventions. Such resources enable patients to make informed decisions, ultimately enhancing their choices and health outcomes.

19,20 Notably, the development of an educational booklet addresses a significant gap in the current literature, as no similar validation studies are known. Based on these considerations, this study aimed to develop and validate a digital educational booklet featuring self-management guidelines for pregnant women with PGP.

MethodsThis was a methodological development and validation study of an educational booklet.

21Healthcare professionals working in the field of obstetrics and Brazilian pregnant women participated in validating the educational booklet. The group of professionals would ideally consist of specialists in the subject, primarily including physiotherapists.

22,23 The second group, for the second stage of the study, was comprised of pregnant women, recruited through social media postings.

24For the selection of healthcare professionals, the Lattes Platform, an online system that contains the

curriculum vitae (CV

) of professionals working in Brazil, was used. These CVs were analyzed to verify the professionals’ experience in obstetrics for at least five years, evidenced by publications in the field. Additionally, the professionals were required to possess a postgraduate degree (i.e., specialization and/or residency) in obstetrics and/or a specialist title, and/or the publication of articles in the field of women’s health and/or relevant experience in the area within the last five years. For the selection of pregnant women, the criteria included being 18 years or older, being literate, self-reporting PGP related to pregnancy for at least 4 weeks, and being currently undergoing prenatal care.

Regarding exclusion criteria, participants from both groups were excluded if they did not maintain contact for more than 30 days or if they did not complete the evaluation form entirely.

For the group of healthcare professionals, a Snowball sampling strategy was employed to enhance the diversity of the sample and support the resolution of potential ties during the validation process. In this method, initial participants were asked to refer to eligible professionals. All suggested individuals were subsequently screened by the research team to ensure compliance with the study’s inclusion criteria prior to being invited to participate. Upon reaching the intended number of healthcare professionals, which was based on literature recommendations to ensure sample representativeness and avoid ties in the process, and following participant acceptance, the professionals completed online forms to evaluate the educational booklet.

22,25 After the adjustments were made, the educational booklet was submitted for analysis by the target audience.

The sample size for the target audience was determined based on data saturation; specifically, data collection was discontinued once no new suggestions or comments emerged from the participants. This approach ensured that the material had reached content consensus regarding its clarity, relevance, and presentation. The criterion is consistent with methodological recommendations for validation studies of educational booklets, in which participant recruitment is concluded when feedback becomes repetitive or stable, indicating that consensus has been achieved.

22,26 Pregnant women were subsequently invited to evaluate the developed material, and all data collection was conducted online through electronic forms.

Participants were recruited using the snowball sampling method. Initially, 23 healthcare professionals were suggested for participation, and the research team contacted those who met the inclusion criteria until the target number of nine was reached.

22To support the development of the digital educational booklet, a literature search was conducted in the MEDLINE/PubMed, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) databases based in the terms “pelvic pain”, “low back pain”, “pregnancy” and “back pain”. In MEDLINE/PubMed the following search string was used: (“pelvic pain” AND “low back pain” AND “back pain” AND “pregnancy”), filtered for review articles published between 2012 and 2022. This search retrieved 58 articles, of which three were considered directly relevant and used as the foundation for the booklet’s content. In SciELO and LILACS, the same string was applied, resulting in four and 19 articles, respectively, but none were deemed relevant for the intended purpose. One additional article was identified through a manual search. The selection focused on review articles and clinical guidelines addressing the management of PGP during pregnancy. PGP is a term widely adopted in the scientific literature, which is why it was used in this manuscript. However, in the educational booklet, the broader term “pelvic” pain was intentionally chosen to facilitate understanding and ensure accessibility for pregnant women who are not familiar with technical terminology.

After the compilation and review of the bibliographic references, a laboratory team meeting was held to discuss the aspects identified in the literature. Based on this analysis, three key components were defined: the informational/educational context, self-management, and health promotion. Once the topics were established, the next step involved creating the layout and preliminary text of the educational booklet, with a consistent commitment to utilizing clear and concise language.

18 Illustrative images and material design were also defined, utilizing the Canva website as a tool for this stage.

The validation process was divided into two stages, the first of which focused on healthcare professionals. In this stage, professionals completed an online form adapted from a literature instrument for evaluating the educational booklet.

27 The form consisted of seven sections blocks: 1. professional identification data; 2. Content evaluation; 3. Language analysis; 4. Illustrations; 5. Booklet structure; 6. Booklet title definition; and 7. Blank space for suggestions. A Likert scale from 1 to 4 was used to respond, where: (1) strongly disagree and (4) strongly agree. In cases where “strongly disagree” or “partially agree” options were selected, professionals were required to provide justifications for their responses.

Following the professional evaluations, meetings were held among the research team to implement suggested adjustments. Subsequently, the modified material proceeded to the second validation stage, involving analysis by the target audience. Pregnant women provided feedback using a validation form containing six sections: 1. Demographic and obstetric data for verification of inclusion criteria; 2. Appearance (language, illustrations, and design); 3. Content; 4. Presentation of instructions; 5. Motivation; and 6. Blank space for comments. Pregnant women were given the options of (1) yes, (2) partially, and (3) no, with the need to justify choices when selecting “partially” or “no”.

Upon completion of this stage, the material underwent final refinement by the research project team, wherein all necessary adjustments were incorporated.

Regarding the statistical analysis for the quantitative analysis of healthcare professionals’ data, the item-level Content Validity Index (CVI) was calculated for each item, measuring the proportion of agreement among experts regarding the material. According to the literature, results above 0.78 are considered adequate.

28 If this threshold was not met, the item underwent revision and modification based on received feedback. In addition, a global scale validation of the educational booklet was conducted, for which results above 0.8 were considered acceptable.

28For the target audience, the Percentage of Absolute Agreement (PAA) was calculated based on the sum of positive responses from participating pregnant women with PGP, divided by the total number of evaluations. A minimum agreement of 75% was considered acceptable.

29 Qualitative suggestions provided by the participants were analyzed using discourse analysis for each individual. These suggestions were grouped according to evaluation sections, which include content adequacy, language, illustrations, booklet structure, and general suggestions.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Federal University of São Carlos (CAAE: 64194322.8.0000.5504, opinion Nº. 5.748.536), in accordance with national regulations and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

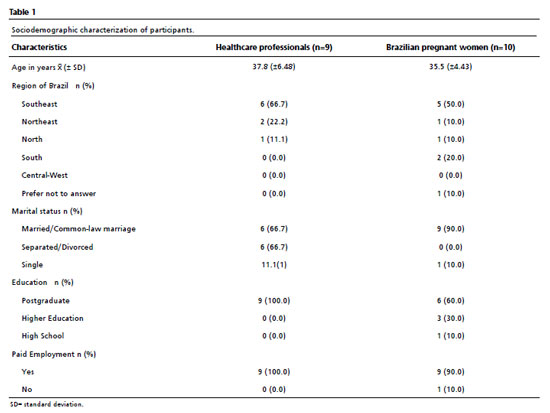

ResultsA total of nine healthcare professionals and ten pregnant women participated in the validation process. All selected participants within the specialist group were women and physical therapists, representing the group of health specialists. As for the target audience group, since the participants were recruited through social media outreach, no formal records of invitations or refusals were maintained. Therefore, the final number of participants in this group was ten pregnant women (one in the first trimester, two in the second, six in the third, and one participant did not report the trimester). The participant descriptions are presented in Table 1. The pregnant women provided information on clinical and obstetric aspects. Among them, 40%(4) had no previous pregnancies, 30%(3) had two pregnancies, 20%(2) had three, and 10%(1) had four or more. Regarding the onset period of PGP, 40%(4) reported it started in the first trimester, 40%(4) in the second, and 20%(2) in the third trimester. When asked if they experienced pain before pregnancy, all participants reported they did not. Finally, regarding medication use during pregnancy, 80% of participants stated they used medication.

The initial version of the educational booklet consisted of nine pages, divided into: cover, presentation of booklet objectives, definition of PGP and its relation to the gestational period, prevention guidelines, possible practices to alleviate pain, references, and back cover. In the practical guidelines section, low-cost non-pharmacological treatments with low health risks for pregnant women were addressed, such as thermotherapy resources, manual therapy, and stretching exercises, each described and illustrated with photos demonstrating proper execution.

The illustrations used were exclusively created for the educational booklet, with a volunteer participant from the research group serving as the model, who consented to the use of her image by filling out an image consent form. The graphic design was chosen to make it more suitable for the target audience, with harmonious and soft colors (pastel pink, green, and orange).

The final version of the digital educational booklet comprises ten pages, titled: “What You Need to Know About Gestational Pelvic Pain,” structured as follows: 1. Introduction to the booklet; 2. Definition and localization of pain; 3. Relationship between pelvic pain and pregnancy and prevention tips; 4. Self-management instructions for pain; 5. References.

To define the booklet title, the following options were presented: 1. Pelvic Pain Relief: A Guide for Pregnant Women, 2. Pregnancy and Pelvic Pain: What You Need to Know, and 3. Guide to Pelvic Pain Relief During Pregnancy. Options 2 and 3 were chosen by 4 participants each, while only one professional chose option 1. Regarding the evaluation of the complete educational booklet, analysis was conducted using the item- level CVI and globally for the entire material, as described in Table 2.

The sections of content (D and F) and language (D) showed borderline results with CVI = 0.78, and were improved based on professionals’ suggestions. Regarding the global CVI, the result was 0.93, indicating that the educational booklet met the acceptability standard and was considered validated by healthcare professionals. Table 3 presents the validation professionals’ suggestions for improving the booklet, which were accepted along with their justifications.

The PAA was used to assess the validity of the material, as described in Table 4. The educational booklet met the acceptability criteria and was considered validated by the pregnant women who participated in the study, achieving a global PAA of 89.2% from the target audience. The results are presented for each item in the form sections and globally.

Among the results presented, only item C “Did you feel comfortable performing the instructions?” in the “Instructions” section did not reach 75% agreement, indicating that it could be improved. For this purpose, the following suggestions from the pregnant participants on this topic were considered: “As I am at the end of my pregnancy (39 weeks), unfortunately, I cannot apply all the stretching methods presented, but if I were in the beginning of the 3rd trimester, or earlier, I would definitely use them.”; and “Some positions I find uncomfortable, I don’t feel safe performing them.”.

Based on these observations, an instruction was added to the educational booklet advising pregnant women that, if they do not feel confident performing a certain position, they should refrain from doing so or request the support/presence of another person. It was also indicated that, depending on the stage of pregnancy, some postures may be more difficult to perform, thereby prioritizing the users’ safety and comfort. Other suggestions were also received:

1. Appearance: “I believe the colors, size, and font style are not very appealing.”; “I would increase the font size to make it easier to read on a cellphone.”; and “Too much text with small font size makes reading tiring.”

2. Content: “I would make the text more direct to improve adherence.”; and “Some sections I found too long. I suggest summarizing.”

3. Motivation: “Due to my gestational stage”

Although these observations highlight important aspects related to accessibility and engagement, they did not result in modifications in this version, since, according to the adopted methodology, only items with agreement below 75% were mandated to be revised.

29 As all other items showed an PAA above this threshold, the suggestions were recorded for possible future adaptations.

DiscussionThe educational booklet developed in this study was validated by both healthcare professionals and pregnant women, confirming its clarity, relevance, and efficacy as a self-management tool for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. The high CVI (0.93) and PAA (89.2%) scores attest to the robustness of the validation process and confirm that the material achieved both expert consensus and user acceptability, aligning with recommended thresholds in the literature. Challenges in performing certain exercises during late pregnancy were acknowledged and appropriately addressed in the final version.

While it is recognized that educational booklets alone do not guarantee knowledge acquisition or behavior change, given that transformation depends on the individual’s willingness to engage, it is evident that such resources facilitate education, autonomy, and health promotion, thereby potentially influencing the quality of life for a significant number of individuals.

18The safety concerns raised by pregnant women regarding certain exercises, especially in relation to their gestational stage, were acknowledged as important limitations requiring intervention. Considering that the educational booklet will be accessed by women at different stages of pregnancy, it is essential that its content provides safe guidance for all users. Although there is a limitation in ensuring complete safety due to the possibility of the material being used without the supervision of a healthcare professional, adaptations were made to the exercises and additional care instructions were included in order to mitigate risks and promote safe use of the content.

Developing an educational booklet is a challenging endeavor, as it requires conceptual understanding of the addressed topic while translating scientific knowledge into accessible language for the target population. Accordingly, literature suggests that these materials should be informative, with accessible language and an attractive appearance to fulfill their role of facilitating learning on a specific topic.

18It is paramount to highlight that PGP is a prevalent complaint during pregnancy and has a significant impact on the quality of life of affected women.

3-6 Therefore, the content of the educational booklet should include information on the definition of PGP and its relation to pregnancy, preventive measures, and possible self-management practices based on current literature.

15 This is essential to ensure an impact on pain management, which constitutes the primary objective of the material.

Beyond their educational purpose, these materials play an important role in health promotion, as they enable awareness and information dissemination to the population. This leads to health improvements by fostering autonomy and self-care in patients, thereby representing a low-cost intervention for the population.

16-18Based on reports identified in the literature, there is a recurring scenario of neglect faced by pregnant women with PGP, both in clinical settings and in social and occupational contexts. These reports frequently highlight a lack of understanding from healthcare professionals, family members, employers, and society in general, contributing to feelings of helplessness and insecurity during pregnancy.

10 Negative comments and lack of knowledge about PGP reinforce the perception that the pain is being invalidated. This context, combined with inadequate support, can compromise the mental health and quality of life of pregnant women and is also associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

9 Furthermore, reports indicate that, even in the presence of clear complaints, many women with PGP experience neglect from healthcare providers and often do not receive any form of treatment.

10In light of this context, the educational booklet developed in this study stands out as a relevant tool, as it is an educational and self-management resource that is reliable, readily understood, and offers practical and accessible strategies. It has the potential to empower pregnant women and support the development of greater autonomy in the face of a healthcare system that, at times, does not provide adequate clinical conditions for the management of PGP.

10This study has some limitations. The validation process involved a relatively small and homogeneous sample, including nine healthcare professionals (all female physiotherapists) and ten pregnant women, most with higher educational levels. These factors may have facilitated understanding of the content and adherence to the material but consequently limit the generalizability of the findings. Although participants from four Brazilian regions were included, there was no representation from the Central-West region. Considering the country’s territorial extension and sociocultural diversity, future studies should include a larger and more diverse sample, with professionals from different backgrounds and pregnant women of varying educational levels, to strengthen the validity and applicability of the material across distinct contexts. Furthermore, participants’ information was self-reported, which may have introduced a degree of recall or information bias.

Another limitation refers to the exclusive use of digital dissemination, which, although cost-effective and wide-reaching, may restrict access for women with low digital literacy or limited internet availability. To enhance equity and applicability, future adaptations should include printed versions and alternative dissemination strategies in healthcare services. Finally, this study focused solely on the development and validation of the booklet; clinical outcomes such as pain reduction, functional improvement, and decreased healthcare demand were not evaluated. Future research should test the effectiveness of the material as a clinical intervention and its potential impact on self-management and quality of life among pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain.

In conclusion, the educational booklet developed and validated in this study demonstrated high content and appearance validity, confirming its clarity, relevance, and applicability. It represents an evidence-based, culturally adapted, and accessible resource to support the self-management of pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy. The material can be incorporated into prenatal and physiotherapy care as a complementary tool for health education and promotion, fostering autonomy, self-care, and maternal well-being. Broader dissemination, particularly through digital platforms, may help reduce informational gaps and promote equitable access to evidence-based guidance for pregnant women across different regions of Brazil.

AcknowledgmentsWe would like to thank the participants who made this study possible, the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) - number: 2022/10483-8 for their financial support in carrying out this project.

References1. Conder R, Zamani R, Akrami M. The Biomechanics of Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2019;4 (4): 72.

2. Chabbert M, Panagiotou D, Wendland J. Predictive factors of women’s subjective perception of childbirth experience: a systematic review of the literature. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2021; 39 (1): 43-66.

3. Verstraete EH, Vanderstraeten G, Parewijck W. Pelvic Girdle Pain during or after Pregnancy: a review of recent evidence and a clinical care path proposal. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2013; 5 (1): 33-43.

4. Burani E, Marruganti S, Giglioni G, Bonetti F, Ceron D, Cozzi Lepri A. Predictive Factors for Pregnancy-Related Persistent Pelvic Girdle Pain (PPGP): A Systematic Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023; 59 (12): 2123.

5. Gashaw M, Yitayal MM, Zemed A, Nigatu SG, Kasaw A, Belay DG,

et al. Level of activity limitations and predictors in women with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: Prospective cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022; 78: 103754.

6. Ceprnja D, Chipchase L, Liamputtong P, Gupta A. “This is hard to cope with”: the lived experience and coping strategies adopted amongst Australian women with pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22: 96.

7. Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: an update. BMC Med. 2011; 9: 15.

8. Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008; 17 (6): 794-819.

9. Robinson PS, Balasundaram AP, Vøllestad NK, Robinson HS. The association between pregnancy, pelvic girdle pain and health-related quality of life - a comparison of two instruments. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018; 2: 45.

10. Elden H, Lundgren I, Robertson E. Life’s pregnant pause of pain: pregnant women’s experiences of pelvic girdle pain related to daily life: a Swedish interview study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2013; 4 (1): 29-34.

11. Gausel AM, Malmqvist S, Andersen K, Kjærmann I, Larsen JP, Dalen I,

et al. Subjective recovery from pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain the first 6 weeks after delivery: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Eur Spine J. 2020; 29 (3): 556-63.

12. Robinson HS, Vøllestad NK, Veierød MB. Clinical course of pelvic girdle pain postpartum - impact of clinical findings in late pregnancy. Man Ther. 2014; 19 (3): 190-6.

13. Mannava P, Durrant K, Fisher J, Chersich M, Luchters S. Attitudes and behaviours of maternal health care providers in interactions with clients: a systematic review. Global Health. 2015; 11: 36.

14. Ceprnja D, Lawless M, Liamputtong P, Gupta A, Chipchase L. Application of Caring Life-Course Theory to explore care needs in women with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. J Adv Nurs. 2022; 78 (8): 2586-95.

15. Clark-Smith M, Tichband L, Dufour S. Pregnancy-related Pelvic Girdle Pain: Irish Physiotherapist’ Perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Reprod Sci. 2019; 3 (2).

16. Svahn Ekdahl A, Fagevik Olsén M, Jendman T, Gutke A. Maintenance of physical activity level, functioning and health after non-pharmacological treatment of pelvic girdle pain with either transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation or acupuncture: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2021; 11 (10): e046314.

17. Mackenzie J, Murray E, Lusher J. Women’s experiences of pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain: A systematic review. Midwifery. 2018; 56: 102-11.

18. Vieira ASM, Castro KV-F, Canatti JR, Oliveira IAVF, Benevides SD, Sá KN. Validation of an educational booklet for people with chronic pain: EducaDor. BrJP. 2019; 2 (1): 39-43.

19. Gazos WMJ, Cavalcente FML, Galindo Neto NM, Joventino ES, Moreira RP, Barros LM. Tecnologias Educacionais Disponíveis para Orientação e Manejo da Dor. Rev Enferm Atual In Derme. 2022; 96 (40): e-021324.

20. Paiva APRC, Vargas EP. Material Educativo e seu público: um panorama a partir da literatura sobre o tema. Rev Práxis. 2017; 9 (18): 89-99.

21. Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, Westerman MJ, Patrick DL, Alonso J,

et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018; 27 (5): 1159-70.

22. Santos MP, Farre AGMC, Sousa LB. Preparation and validation of contents concerning the use of preservatives. Rev Enferm UFPE. 2019; 13 (5): 1308-16.

23. Andrade SSC, Gomes KKS, Soares MJGO, Almeida NDV, Coêlho HFC, Oliveira SHS. Construção e validação de instrumento sobre intenção de uso de preservativos entre mulheres de aglomerado subnormal. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2022; 27 (7): 2867-77.

24. Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Recommendations for the Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the DASH & QuickDASH Outcome Measures Contributors to this Document. Toronto (Canadá): Institute Work & Health; 2007. [

Internet]. [access in 2024 Apr 10]. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26500094125. Vinuto J. Snowball sampling in qualitative research: an open debate. Tematicas. 2014; 22 (44): 203-20.

26. Reberte LM, Hoga LAK, Gomes ALZ. O processo de construção de material educativo para a promoção da saúde da gestante. Rev Latino-Am Enfem. 2012; 20 ( 1): 101-8.

27. Luz ZMP da, Pimenta DN, Rabello A, Schall V. Evaluation of informative materials on leishmaniasis distributed in Brazil: criteria and basis for the production and improvement of health education materials. Cad Saúde Pública. 2003 Mar; 19 (2): 561-9.

28. Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006; 29 (5): 489-97.

29. Stemler SE. A Comparison of Consensus, Consistency, and Measurement Approaches to Estimating Interrater Reliability. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2004; 9 (4): 1-11.

30. World Health Organization (WHO). Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. Geneva: WHO; 2021. [access in 2024 Apr 10]. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020924Author’s contributionGozzer LT: Conceptualization (Equal); Data curation (Equal); Formal Analysis (Equal); Funding acquisition (Lead); Investigation (Equal); Methodology (Equal); Project Administration (Equal); Resources (Equal); Software (Equal); Visualization (Equal); Writing original draft (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal). Araujo Silva CM: Conceptualization (Equal); Formal Analysis (Equal); Investigation (Equal); Methodology (Equal); Project Administration (Equal); Supervision (Equal); Visualization (Equal); Writing original draft (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal). Mancini L and Almeida Santos CC: Validation (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal). Rodrigues-des-Souza DP and Albuquerque-Serdín F: Supervision (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal). Sartorato Beleza AC: Conceptualization (Equal); Formal Analysis (Equal); Methodology (Equal); Project Administration (Equal); Resources (Supporting); Supervision (Equal); Visualization (Equal); Writing - review & editing (Equal).

All authors approved the final version of the article and declared no conflict of the interest.

Data availabilityAll datasets supporting the result of this study are included in the article.

Received on February 26, 2025

Final version presented on October 29, 2025

Approved on October 30, 2025

Associated Editor: Melania Amorim

; Clara Maria de Araujo Silva2

; Clara Maria de Araujo Silva2 ; Leticia Mancini3

; Leticia Mancini3 ; Caroline Cristina de Almeida Santos4

; Caroline Cristina de Almeida Santos4 ; Daiana Priscila Rodrigues-de-Souza5

; Daiana Priscila Rodrigues-de-Souza5 ; Francisco Alburquerque-Sendín6

; Francisco Alburquerque-Sendín6 ; Ana Carolina Sartorato Beleza7

; Ana Carolina Sartorato Beleza7