ABSTRACT

Perinatal palliative care is an emerging field in fetal medicine, which encompasses fetal abnormalities with conditions that limit fetal or neonatal life in a humanized manner. This protocol was developed based on a literature review and proposes a care model for pregnant women with a prenatal diagnosis of such conditions at the Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP). The objective is to standardize care and ensure clarity in communication with parents and family members. The topics covered include: perinatal palliative care, fetal diagnosis of life-limiting conditions, communication, eligibility criteria, conduct, prenatal care, birth, perinatal bereavement, and the puerperal period. It should be noted that this protocol was developed considering regions and/or health institutions with limited technological and/or financial conditions and can be adapted to different contexts.

Keywords:

Palliative care, Perinatology, Prenatal care, Congenital abnormalities

RESUMO

O cuidado paliativo perinatal é um campo emergente na medicina fetal, que engloba anormalidades fetais com condições limitantes à vida fetal ou neonatal de forma humanizada. O presente protocolo foi elaborado a partir de uma revisão da literatura e traz uma proposta de modelo de atendimento para as gestantes com diagnóstico pré-natal de tais condições, no Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP). O objetivo é padronizar a assistência e garantir clareza na comunicação com os pais e familiares. São abordados os tópicos: cuidados paliativos perinatais, diagnóstico fetal de condição limitante da vida, comunicação, critérios de elegibilidade, condutas, pré-natal, nascimento, luto perinatal e puerpério. Destaca-se que esse protocolo foi elaborado considerando regiões e/ou instituições de saúde com condições tecnológicas e/ou financeiras limitadas, podendo ser adaptado a diferentes contextos.

Palavras-chave:

Cuidados paliativos, Perinatologia, Cuidado pré-natal, Anormalidades congênitas

IntroductionThe implementation of new routines in healthcare institutions requires the creation of protocols that contribute to the continuous improvement of care, patient safety, and communication among teams.

1 In perinatal palliative care, systematization through continuing education and protocols ensures greater uniformity in the care provided for pregnant women and fetuses with life-limiting conditions.

2,3The concept of palliative care was extended to perinatology in 1997; however, in Brazil, until 2017, there was no protocol for the follow-up of palliative care during prenatal care. In 2025,

Lei 15,139 (the Brazilian Law) was enacted, establishing the

Política Nacional de Humanização do Luto Materno e Parental (National Policy for the Humanization of Maternal and Parental Grief,) which aims to ensure humanized care for women and families during grief due to gestational loss, fetal death, or neonatal death, and to provide public services to reduce potential risks and vulnerabilities for those involved. The law also provides for the promotion of awareness campaigns, protocols, professional education, and specialized care for pregnant women and their families.

4In this context, the present protocol was developed to guide clinical practice at the maternity unit of the

Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP), which provides care for pregnant women and their fetuses diagnosed with life-limiting conditions who are candidates for perinatal palliative care. This document guides healthcare teams through the necessary steps to offer compassionate care, ensuring clarity in decision-making, standardized referrals, and more effective interprofessional communication. It is noteworthy that this protocol may be adapted to other regions and institutions with similar technological and/or financial resources.

MethodsA scoping review of the literature was conducted in the MEDLINE/PubMed and

Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde (BVS) (Virtual Health Library) (BIREME/SciELO/LILACS) databases, using the following descriptors: "prenatal care" and "palliative care".

All study designs published between February 2015 and May 2025 involving the selected descriptors were considered for inclusion. The following were excluded: studies that did not address perinatal palliative care during pregnancy; studies that did not present guidelines for models of care; studies written in languages other than English, Portuguese, or Spanish; and studies focusing exclusively on palliative care for a specific disease or group of diseases. For the definition of key concepts, other studies outside the eligibility criteria were also referenced.

The selected articles were analyzed, highlighting available resources and the experience in care in the fetal medicine unit at IMIP. Based on these sources, the concept of perinatal palliative care, the eligible fetal anomalies and their diagnostic criteria, communication guidelines, prenatal and delivery care, bereavement, and postpartum approaches were defined, and besides the development of a birth plan to be discussed with patients and families during prenatal care, was also included.

After the literature review and protocol drafting, the document was presented in two clinical meetings (internal and external) for discussion with specialists in perinatal medicine and subsequently in two additional meetings with three experts (internal and external members).

Perinatal palliative carePerinatal palliative care is a compassionate, family-centered model of care for pregnant women who choose to continue their pregnancy after a prenatal diagnosis of a fetus with a life-limiting condition. It prioritizes the patient's expectations and choices, aiming to relieve suffering, preserve dignity, and promote quality of life, respecting the beliefs and wishes of families regardless of the newborn's survival time. It provides families with an opportunity to experience both birth and the dying process with minimal interference.

3,5With technological advances, the diagnosis of fetal malformations has become possible at increasingly earlier gestational ages, making palliative care essential from prenatal care through the postnatal period for eligible patients.

Diagnosis of Life-Limiting Fetal ConditionsFetal malformations occur in approximately 3% of pregnancies and account for about 40% of perinatal deaths.

6 Lethal fetal conditions, such as anencephaly, alobar holoprosencephaly, bilateral renal agenesis, bilateral multicystic kidneys, and trisomies 13 or 18, occur in about 2% of the cases.

7Fetal malformations detected by ultrasonography may be associated with chromosomal abnormalities, and genetic diagnosis may be obtained through invasive tests (chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis, or cordocentesis for fetal karyotyping or microarray), depending on availability, or through noninvasive prenatal screening tests (NIPT - non-invasive prenatal test). In cases of suspected anomalies, diagnosis must be confirmed after birth and, when indicated, the specific neonatal palliative care protocol it should be followed. (Neonatology).⁸

It is important to emphasize that a diagnosis of a lethal fetal malformation does not necessarily imply immediate death; it may occur in intrauterine, during the peripartum or neonatal period, or even months after birth.

9 There is no consensus on which malformations should be considered lethal, as prognosis can vary and, in rare cases, survival may extend beyond expectations.

10The fetal medicine specialist is generally responsible for diagnosing fetal malformations identified during pregnancy.

11,12 In the context of palliative care, for families who wish to continue the pregnancy, the use of terms such as "lethal" or "incompatible with life" to describe life-limiting conditions may cause hopelessness, and hasty communication may lead to lasting trauma.

13 The moment of diagnosis represents a period of extreme vulnerability for parents and families. Some pregnant women will research the fetal condition, others may feel guilty, and some will remain in shock.

10,14For the purpose of this protocol, at IMIP, all patients must have the fetal diagnosis confirmed by a fetal medicine specialist from the institution, as well as the follow-up ultrasonographic evaluations. It is recommended that, for patients who choose to continue the pregnancy, the terms "life-limiting condition" or "fetal and/or neonatal life-limiting condition" be used instead of "lethal malformation," in order to reduce the emotional impact on families.

Communication The communication of a fetal condition must be conducted individually, using clear and accessible language, in a private setting, and with respect for the patient's and family's beliefs and questions, with proper documentation in the medical record. The conversation may begin by asking what the patient already knows about her baby, especially if the diagnosis has been previously suspected.

10,12,15 Communication can be structured in two stages: first, discussing the fetal life-limiting condition, and subsequently, within the same meeting, informing the patient about referral to palliative care. Referral can occur at any point in the pregnancy once the diagnosis is established, and should be made by the fetal medicine specialist.

12Communication is a key tool for quality healthcare delivery, representing a skill that can be learned and refined. Several studies propose techniques for more empathetic and effective communication. The following principles and techniques are suggested for difficult conversations in palliative care: choose a calm and private environment; introduce oneself; provide clear information about diagnosis and prognosis; gather relevant data (e.g., test results); speak clearly and avoid technical jargon; communicate progressively, assessing what the patient knows and wants to know; avoid false reassurance; allow time for the patient to speak; practice active listening; be aware of nonverbal communication (from both professional and patient); involve family or caregivers when possible; balance realism with hope; and begin a care plan as soon as feasible.

16,17 This communication should be carried out both by the fetal medicine professional during the ultrasound examination and by the healthcare professionals monitoring the patient.

During these discussions, information should be provided regarding the fetal anomaly, its current status, and its natural evolution, addressing all parental questions about the condition, follow-up, and the meaning of palliative care, including what procedures will be performed with the fetus. At this stage, referral to psychological support services is strongly recommended.

12,16CandidatesEligibility for perinatal palliative care varies according to country, available resources, and cultural factors. In general, fetal or neonatal life-limiting diseases are the main indications for this type of care.

9,12,18In Brazil, within the field of fetal malformations, pregnancy termination is legally permitted only in cases of anencephaly. For other anomalies with limited survival prognosis, elective termination is not legally provided for, although judicial authorization may be sought if the patient so desires. In such scenarios, prenatal follow-up becomes essential, both for women who choose to continue the pregnancy in cases of anencephaly and for those with other life-limiting conditions whose pregnancy will continue (by patient choice or judicial decision). It is crucial that healthcare teams are trained to provide guidance, emotional support, and counseling.

9,18The indication for palliative care should consider fetal diagnosis and prognosis, as well as the personal meaning of the condition for the patient and her family.

9,19 Several anomalies identifiable during pregnancy may have a limited prognosis and should be reassessed after birth (Table 1).

3,12,14,15,18,20 Palliative care may coexist with intensive care approaches when appropriate, as any patient with a life-threatening condition can receive palliative care, even if death is not imminent.

17 However, in cases involving long-term life-limiting conditions, palliative care is often ethically more appropriate than intensive interventions, as it prevents suffering without altering the outcome.

9,21 In addition to the listed conditions, other anomalies may be considered on a case-by-case basis, depending on prognosis and therapeutic resources available (e.g., complex congenital heart disease, large fetal tumors, airway obstructions, rare syndromes). When prognosis is uncertain, a multidisciplinary clinical meeting should be convened for discussion and consensual inclusion in palliative care. Neonatal follow-up may redirect the therapeutic plan according to the newborn's clinical evolution, family values, and available healthcare resources.

ConductsGiven the various life-limiting fetal conditions listed in this protocol, a schematic summary was developed, including the diagnosis and the preferred route of delivery for patients who will continue prenatal follow-up at the institution (Table 1). It is emphasized that the timing of pregnancy termination (labor induction or cesarean section) should be guided by the patient's comorbidities or medical indications. If the patient presents no comorbidities and maintaining the pregnancy does not pose additional maternal risk, spontaneous labor should be awaited.

Prenatal carePrenatal care in fetal medicine consists of monitoring pregnant women through counseling, diagnosis, screening, and risk assessment of adverse maternal and fetal conditions

6 In the presence of a prenatal diagnosis of a fetus with a life-limiting condition, prenatal counseling must be conducted by a multidisciplinary team composed of an obstetrician, fetal medicine specialist, neonatologist, psychologist, social worker, anesthesiologist, surgeon, and other qualified professionals, depending on the diagnosed congenital abnormality.

11,12The pregnant woman and her family must receive compassionate support, appropriate referrals, management of comorbidities, and both routine and condition-specific prenatal examinations, aiming to identify the cause and provide general guidance about the pregnancy and fetal condition.

Palliative care should be introduced to the family, with the development of a care plan jointly created by the healthcare team and the patient. The plan must be respected regardless of which professionals are present at the time of birth.

13With the diagnosis in the gestational period, families often experience anticipatory grief. Being informed of a possible perinatal death allows family members to reflect on their wishes and beliefs and gives the team time to prepare for delivery.

8 It is essential to validate the feelings of the pregnant woman and her relatives, emphasizing their role as caregivers. Parenthood persists regardless of the pregnancy outcome; thus, it is important to help families create memories, value their choices, and give meaning to the pregnancy.

11During prenatal care, discussions may include how to respond to strangers who ask about the pregnancy, suggestions for books or reading materials, conversations about cultural or religious aspects, and the possibilities of home-based perinatal palliative care, depending on the fetal anomaly.

7,16Healthcare professionals should gather diagnostic information, practice effective communication, repeat information whenever requested, provide ongoing clinical follow-up, and plan the next steps collaboratively with the pregnant woman and her family or chosen companions.

3,5Guidelines for prenatal follow-upPrenatal care in fetal medicine at IMIP is conducted at the women's outpatient clinic by specialists in fetal medicine, with possible participation of medical residents and students.

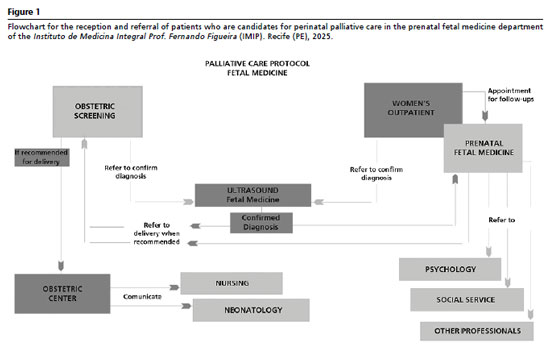

Patients' care begins in the fetal medicine sector, the women's outpatient clinic, or the obstetric screening/emergency unit. Patients with suspected fetal diagnoses should be referred to the fetal medicine unit for diagnostic confirmation through ultrasonography performed by specialists in fetal medicine or through invasive testing, as indicated and depending on institutional availability. If a life-limiting fetal condition is confirmed, the patient will be referred to fetal medicine prenatal care to initiate perinatal palliative care (Figure 1).

The prenatal follow-up of these pregnant women was organized in a structured care pathway at the women's outpatient clinic at IMIP (Figure 2). The initial assessment may be conducted by the fetal medicine team. However, if the first consultation occurs in the high-risk or routine prenatal care clinic and a fetal malformation is detected, the initial assessment can be carried out at that point, with a follow-up appointment scheduled with the fetal medicine unit.

1.1) First consultationDuring the first consultation, an interview is conducted by the fetal medicine specialist. Patient identification data are recorded in the medical chart. The patient receives a prenatal card, which must be filled out, and her vaccination card should be reviewed and updated if necessary. Rapid tests and routine laboratory exams are requested, and any previously performed exams are evaluated (Figure 2).

22The interview includes an investigation of personal and reproductive history, lifestyle, occupation, medications in use, complications, maternal comorbidities, and family history. The obstetric history should record the number of pregnancies and deliveries, history of miscarriages or fetal deaths, fetal growth restriction, malformations, twin pregnancies, associated diseases, and type of delivery. Risk factors such as smoking, illicit drug use, alcohol consumption, medications, and radiation exposure must be investigated, along with any pregnancy related or unrelated symptoms. A complete physical examination (clinical, obstetric, and gynecological) must be performed.

6,22When a malformation is suspected, the professional should clarify the etiology, prognosis, and characteristics of the condition; request any necessary confirmatory exams (referral for ultrasonography with fetal medicine); and discuss the possible follow-up and conduct options, such as palliative care or karyotyping by amniocentesis, depending on indication and the patient's and family's wishes.

6,22 The patient should be informed that diagnostic confirmation will occur after the ultrasonography performed by the fetal medicine team, at which point the indication for palliative care will be re-evaluated.

1.2) Cases of pregnancy terminationIn cases of anencephaly, the pregnant woman may choose to terminate the pregnancy without judicial authorization, and should be referred to a maternity hospital (Figure 2). The patient must present an ultrasound report (signed by two physicians) confirming the diagnosis, including photographic documentation (two images: one sagittal and one transverse view of the cephalic pole) demonstrating absence of the cranial vault and brain parenchyma. The patient must also sign an Informed Consent Form (ICF), which must be attached to the medical record.

18In cases of other fetal malformations considered life-limiting conditions, if the patient wishes to terminate the pregnancy, a medical report with confirmatory ultrasonography must be prepared, preferably including a psychological assessment of the pregnant woman, a signed letter from the patient requesting judicial authorization for pregnancy termination, and a referral letter from the attending specialists to the court. The patient may be referred to the social services department for guidance on legal procedures. Once judicial authorization is granted, the patient may be referred for pregnancy termination. If authorization is denied, prenatal care should continue as usual, focusing on palliative care.

18For pregnancies of 22 weeks or more, feticide should be discussed with the patient prior to hospital admission, along with signing the ICF, as it increases the likelihood of successful termination/induction. The procedure should be performed by a fetal medicine specialist, under ultrasound guidance, using intracardiac potassium chloride (KCl).

18 The patient should then be referred to the obstetric unit (at the maternity hospital of her choice) for induction of labor.

1.3) Follow-up consultationsDuring follow-up visits (Figure 2), the diagnosis and management options should be reviewed, and perinatal palliative care should again be offered to the patient and her family.

Continuous and periodic follow-up throughout pregnancy ensures adequate prenatal monitoring and should follow the pre-established schedule for high-risk or routine prenatal care. (monthly until the 28th week, biweekly from the 28

th to the 36

th week, and weekly at term), or at shorter intervals depending on maternal comorbidities.

22 It is important to note that for patients who have opted for perinatal palliative care, more frequent prenatal visits are not necessary solely due to fetal abnormality.

Each visit should include assessment of previously requested exam results (laboratory and ultrasound), verification of vaccination status, targeted physical examination, and identification of associated maternal diseases.

22 In subsequent consultations, a birth plan should be developed based on the patient's and family's wishes, guided by the healthcare professional, and documented both in writing for the patient and in the medical record.

5,12,191.4) ReferralsMultidisciplinary assessment is essential for palliative care follow-up, and psychological referral should be offered whenever desired. Approximately 20% of women experiencing gestational loss develop mental health disorders within one year, making psychological evaluation crucial. Referral to psychiatry should also be considered when necessary, for conditions such as depression, anxiety, or other disorders requiring medication.

23Referral to social services should be made in cases of social vulnerability or when coordination with the patient's local healthcare network is needed.

16In some cases, evaluation by neonatology or pediatric surgery may be required to determine the feasibility of neonatal treatment. Patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia with severe pulmonary hypoplasia, giant omphalocele, severe congenital heart disease, or severe ventriculomegaly may have a potential treatment plan but can still benefit from perinatal and postnatal palliative care.

24 Whenever possible, consultation with a pediatric palliative care specialist is recommended to align prenatal information with postnatal care planning.

1.5) Ultrasound follow-upUltrasound examination is necessary from the patient's first contact with the healthcare service for diagnostic confirmation and appropriate referrals. The frequency of ultrasounds should be determined individually, but at least once per trimester. In addition to providing diagnostic support, these exams also offer opportunities for the patient and family to connect with the baby and create memories

11,16 It should be noted that during the second-trimester morphological ultrasound, measurement of cervical length for preterm birth screening is not recommended in life-limiting conditions (major fetal malformations), since progesterone therapy or cervical cerclage is not indicated in such cases.

25,261.6) Prenatal care planIt is important to establish a checklist outlining the prenatal care plan to be followed at the outpatient clinic — that is, a structured care plan to guide healthcare professionals during consultations and facilitate patient reception at the institution (Figure 3).

Birth PlanThe birth plan provides parents with the opportunity to discuss their needs and expectations, helping them to anticipate and prepare for the grieving process. Studies show that having a birth plan increases parental satisfaction and reduces anxiety, fear, and stress.

11,19 The plan should be developed jointly with family members, obstetricians, neonatologists, and perinatal palliative care specialists, serving as an opportunity to explore and document the parents' wishes.

11,12,19Vaginal delivery should always be encouraged, as it is a physiological process and poses lower maternal risk. Intrapartum fetal monitoring should be discussed among the medical team and family, given the risk of fetal clinical deterioration and intrapartum death; monitoring may be omitted or spaced out if deemed appropriate by the team and in accordance with the parents' wishes.

3,25 It is important to note that vaginal delivery can still be performed even in cases of compromised fetal vitality. However, the clinical conditions of both the mother and fetus must be considered, as well as the family's wishes regarding a cesarean section when the parents desire to meet their baby alive. This decision should also take into account religious beliefs and weigh the potential risks of surgical delivery (Figure 4).

3,16,19 The birth plan should include the baby's and mother's names, family preferences, guidance for healthcare professionals, as well as the mode of delivery and immediate newborn care. It is advisable to discuss religious aspects during the plan's development—such as rituals after birth—and to provide opportunities for parents to create memories (e.g., taking photos), ensuring the family's comfort during this moment.

11,19All topics should be listed in the birth plan, with flexibility for adjustments based on the needs of the mother and family, and space should be provided for individual notes related to each case or institution. The relevant items should be marked according to the agreement reached during consultations. It is important to emphasize that the birth plan serves as a guide to prepare for the moment and may be adapted or modified as needed.

BirthAt birth, the birth plan, if one exists, should be respected, and whenever possible, the delivery should take place in a private environment (If available).

Providing respectful care can help facilitate the grieving process. Healthcare professionals should act as they normally would with newborns who are not receiving palliative care, naturally and empathetically. Performing a physical examination, taking the patient's history, monitoring contractions, explaining delivery room procedures, and following standard care routines can help the patient and her family feel integrated into the maternity experience like any other.

23In case of intrauterine death, the professionals must be prepared to describe the stillborn baby, if requested by the mother, and to explain what will be examined. Descriptions of features such as skin discoloration, peeling, marks, umbilical cord discoloration, edema, and known malformations may help minimize the family's initial shock.

23The neonatologist is generally responsible for the initial assessment, maintaining temperature, ensuring comfort, and preventing respiratory distress in the newborn. Parents should be offered quality time with their baby, and referrals should be made collaboratively at the appropriate moment. When neonatal intensive care is needed, interventions should prioritize comfort, pain relief, and symptom control.

If an intervention no longer contributes to improving the patient's quality of life, treatment should be reassessed. Withholding invasive support or discontinuing ongoing procedures are ethically appropriate measures in cases of lethal or poor prognosis. Conflicts may arise among professionals or between the healthcare team and the family; in such cases, further discussions, second opinions, or additional tests may support shared decision-making.

In cases of spontaneous preterm labor, tocolysis or antenatal corticosteroid therapy should not be performed.

27 Similarly, for preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), antibiotic therapy should not be used to prolong latency. Each case should be discussed with the mother, weighing the risks and benefits of maintaining the pregnancy versus inducing labor.

28Perinatal griefPerinatal grief refers to losses occurring at any point during pregnancy up to the newborn's first month of life. In the event of peripartum death, family preparation must be planned, including communication. The healthcare team's involvement in this experience is crucial for supporting the grieving process. Professionals should be sensitive to each patient's specific needs to ensure comprehensive care. Referral to psychological support should be considered and offered in all cases.

23Nursing and medical teams may offer opportunities to create memories throughout prenatal care, such as performing three-dimensional (3D) ultrasounds and recording videos or fetal heartbeat sounds; taking photos of the baby or body parts; saving a lock of hair (protected by national law)

4; dressing the baby; making placenta prints or hand/footprints; writing letters to the family; keeping hospital bracelets; and preparing a memory box, according to the mother's wishes and staff availability at the time of birth (Figure 4). Cultural and religious beliefs must be respected. Attention should be given to the family structure, baby's name, chosen companion, and privacy.

4,16,23When perinatal death occurs, healthcare professionals should take special care. If the mother does not wish to see the baby, the family should be reassured that such feelings are normal. A family member or companion may be offered the opportunity to see or photograph the baby (to prevent possible regret later), and the mother may do so at another moment if desired. If the family wishes to see the baby, a private space should be provided. The baby should not be washed (to preserve olfactory memory). The mother should be informed about possible malformations and may choose to cover certain areas, and should also be told that spasms (in recent deaths) or skin peeling may occur.

23Families must receive clear information about bureaucratic procedures related to the baby's transport and burial.

29 The medical, nursing, and social service teams should guide them on obtaining a death certificate (D.C.) or referral to the death verification service, when needed, and explain the process for contacting a funeral home, registering at the notary office, and arranging transport. A certificate may be issued with the date and place of birth, the chosen baby name, and, if possible, footprints or fingerprints.

4 Families should also be informed that, if they wish, the stillborn or neonatal death can be registered under the chosen name, legally permitted (in the state of Pernambuco since 2014

30 and, starting in 2025, nationwide

4). The social service team should also be involved in cases of social vulnerability or when coordination with the local health network is needed.

4,11Puerperal periodThe patient who experiences perinatal loss faces the physical and emotional changes without her newborn by her side. Some mothers may initially breastfeed if death occurs in the neonatal period, while others may not have that opportunity when death occurs earlier or when life-limiting conditions prevent feeding.

4,31It is important that the healthcare team should discuss lactation management with the mother. Some may wish to donate breast milk as part of their grieving process. If the mother chooses not to donate, medication can be offered to suppress lactation (Figure 4). The

lei nacional 15.139/2025 (Brazilian National Law) ensures the right of bereaved mothers to donate breast milk.

4Mothers are entitled to maternity benefits in cases of stillbirth or neonatal death (

art. 358 da Instrução Normativa – IN nº 128 de 2022 do PRES/INSS) (Article number), upon presentation of a medical statement.

32 Waged employees under the

Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho (CLT) (Consolidation of Labor Laws) are entitled to 120 days of maternity leave and job stability from pregnancy confirmation until five months after childbirth. This does not apply to pregnancy losses before the 22

nd week (miscarriage), for which the mother is entitled to 15 days of leave. For civil workers (statutory employees), the right for leave duration varies by jurisdiction.

23Psychological follow-up, a support network, and communication with the local primary healthcare team are essential for bereaved mothers. The social service team at the hospital must facilitate coordination with the local health system.

11 A puerperal consultation should be carried out, either at the hospital where the delivery occurred or at a local health center, to provide guidance on postpartum care (surgical wound, breasts, lochia, postpartum depression screening, and puerperal complications).

22,23Final ConsiderationsThis protocol results from a critical synthesis of national and international literature, adapted to the context of a high-risk maternity hospital in the Northeast of Brazil. IMIP, a philanthropic institution within the

Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS) (Brazilian Public Health System), despite limited diagnostic and care resources, serves as a regional reference center, caring for a large number of high-complexity patients. The development of this care model aims to standardize internal workflows, improve interprofessional communication, and guide shared decision-making from prenatal care through the puerperal period. Its pragmatic nature and low additional cost (mainly inherent to hospitalization) make it replicable in institutions with similar profiles, fostering multidisciplinary networks capable of providing family centered perinatal palliative care. Its implementation is recommended with continuous professional education, indicator monitoring (e.g., adherence to birth plans, proportionality of interventions, referrals to Psychology/Social services), and periodic review to ensure ongoing updates and the quality of perinatal palliative care services.

References1. Santos DC, Bernardes DS, Mantovani VM, Gassen M, Jacques FBL, Farina VA,

et al. Implementação dos Protocolos Básicos de Segurança do Paciente: projeto de melhoria da qualidade. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2024; 45 (esp1): e20230312.

2. Tosello B, Haddad G, Gire C, Einaudi MA. Lethal fetal abnormalities: how to approach perinatal palliative care? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016; 30 (6): 755-8.

3. Catania TR, Bernardes L, Benute GRG, Gibeli MABC, NAscimento NB, Barbosa TVA,

et al. When one knows a fetus is expected to die: Palliative care in the context of prenatal diagnosis of fetal malformations. J Palliat Med. 2017; 20 (9: 1020-31.

4. Brasil. Lei nº 15.139, de 23 de maio de 2025. Institui a Política Nacional de Humanização do Luto Materno e Parental e altera a Lei nº 6.015, de 31 de dezembro de 1973. Brasília (DF): DOU de 26 de maio de 2025; Seção 1:1. [access in 2025 Jul 11]. Available from:

https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2023-2026/2025/lei/l15139.htm5. Rusalen F, Cavicchiolo ME, Lago P, Salvadori S, Benini F. Perinatal palliative care: a dedicated care pathway. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021; 11 (3): 329-34.

6. Souza ASR, Lima MMS. Medicina Fetal. 2

nd ed. Rio de Janeiro: MedBook; Recife: Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira (IMIP); 2021.

7. Côté-Arsenault D, Denney-Koelsch E. "Have no regrets": Parents' experiences and developmental tasks in pregnancy with a lethal fetal diagnosis. Soc Sci Med. 2016; 154: 100-9.

8. Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz A, Moczulska H, Grzesiak M, Kaczmarek P. Outcomes of delivery in patients with diagnosed life-limiting fetal condition and evaluation of perinatal palliative care program: a retrospective review of palliative care service over 7 years. BMC Palliat Care. 2025; 24: 38.

9. Bolibio R, Jesus RCA, Oliveira FF, Gibelli MA, Benute GRG, Gomes A,

et al. Cuidados paliativos em medicina fetal. Rev Med. 2018; 97 (2): 208-15.

10. Linebarger JS. Pregnancy accompanied by palliative care. Perspect Biol Med. 2020; 63 (3): 535-8.

11. Cole JCM, Moldenhauer JS, Jones TR, Shaughnessy EA, Zarrin HE, Coursey AL,

et al. A proposed model for perinatal palliative care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017; 46 (6): 904-11.

12. Sidgwick P, Harrop E, Kelly B, Todorovic A, Wilkinson D. Fifteen-minute consultation: perinatal palliative care. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2016; 102 (3): 114-6.

13. Cortezzo DE, Ellis K, Schlegel A. Perinatal palliative care birth planning as advance care planning. Front Pediatr. 2020; 8: 556.

14. Tataj-Puzyna U, Baranowska B, Szlendak B, Szabat M, Węgrzynowska M. Parental experiences of prenatal education when preparing for labor and birth of infant with a lethal diagnosis. Nurs Open. 2023; 10: 6817-26.

15. Bernardes LS, Jesus RCA, Oliveira FF, Benute GRG, Gibelli MABC, Nascimento NB,

et al. Family conferences in prenatal palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2020; 23 (10): 1349-56.

16. Wool C, Catlin A. Perinatal bereavement and palliative care offered throughout the healthcare system. Ann Palliat Med. 2019 Feb; 8 (Suppl. 1): S22-9.

17. Messias AA, Maiello APMV, Coelho FP, D'Alessandro MP. D'Alessandro MP, Pires CT, Forte DN (Coord.). Manual de cuidados paliativos. São Paulo: Hospital Sírio-Libanês; Ministério da Saúde; 2020. 175 p. [access in 2025 Jul 11]. Available from:

https://cuidadospaliativos.org/uploads/2020/12/Manual-Cuidados-Paliativos.pdf18. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas. Manual de gestação de alto risco. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2022. 692 p. [access in 2025 Jul 11]. Available from:

https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/manual_gestacao_alto_risco.pdf19. Cortezzo DE, Bowers K, Cameron Meyer M. Birth Planning in Uncertain or Life-Limiting Fetal Diagnoses: Perspectives of Physicians and Parents. J Palliat Med. 2019 Nov; 22 (11): 1337-45.

20. Fetal Medicine Foundation. Fetal abnormalities. [

Internet]. [access in 2023 Out 3]. Available from:

https://www.fetalmedicine.org/education/fetal-abnormalities21. Perinatal palliative care: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 786. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Sep; 134 (3): e84-9.

22. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Atenção ao pré-natal de baixo risco. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2012. 318 p. [access in 2023 Out 3]. Available from:

https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/cadernos_atencao_basica_32_prenatal.pdf23. Salgado HO. Como lidar com luto perinatal: acolhimento em situações de perda gestacional e neonatal. Lexema: Ema Livros; 2018.

24. Henry CJ, Côté Arsenault D. Family Centered Antenatal Care With a Life Limiting Fetal Condition: A Developmental Theory Guided Approach. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2024; 69 (6): 958-62.

25. Thakur M, Jenkins SM, Mahajan K. Cervical Insufficiency. 2024 Oct 6. In: StatPearls [

Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. [access in 2025 Jul 11]. Available from:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30247829/26. Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Rehal A, Brizot ML, Serra V, Da Fonseca E,

et al. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in twin gestations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Dec; 229 (6): 599-616.

27. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin N

o. 171: Management of Preterm Labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Oct; 128 (4): e155-64.

28. Bond DM, Middleton P, Levett KM, van der Ham DP, Crowther CA, Buchanan SL,

et al. Planned early birth versus expectant management for women with preterm prelabour rupture of membranes prior to 37 weeks' gestation for improving pregnancy outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Mar; 3 (3): CD004735.

29. Pedraza EC, Vokinger AK, Cleves D, Michel G, Wrigley J, Baker JN,

et al. Grief and Bereavement Support for Parents in Low- or Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024 May; 67 (5): e453-71.

30. Poder Judiciário do Estado de Pernambuco. Corregedoria‑Geral da Justiça. Provimento nº 12, de 8 de setembro de 2014. Regulamenta o assento de óbito fetal, facultando aos pais a identificação do filho natimorto; orienta Oficiais do Registro Civil das Pessoas Naturais, e dá outras providências. Diário da Justiça Eletrônico, Recife, Edição 166, p. 69, 11 de setembro de 2014. [access in 2025 Jul 11]. Available from:

https://portal.tjpe.jus.br/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=ee3a0f71-d9e7-8aa2-9fb9-e85c2a7e8694&groupId=2901031. Alves LF, Silva DM, Ribeiro RB, Araújo TO, Silva Ferreira BE. Cuidados paliativos perinatais: abordagem diante anomalias congênitas que ameaçam a continuidade da vida. Nurs Ed Bras. 2023; 26 (300): 9645–52.

32. Ministério do Trabalho (BR). Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social. Instrução Normativa PRES/INSS n° 128, de 28 de março de 2022. Disciplina as regras, procedimentos e rotinas necessárias à efetiva aplicação das normas de direito previdenciário. Brasília (DF): DOU de 29 de março de 2022; Edição 60, Seção 1, Pág. 132. [

Internet]. [access in 2023 Out 3]. Available from:

https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativa-pres/inss-n-128-de-28-de-marco-de-2022-389275446Authors' contributionSouza ASR, Figueredo DVA: project design and conception, interpretation and analysis of included studies, manuscript writing and revision.

Faquini SLL, Guerra GL: project design and conception, manuscript revision.

All authors approved the final version of the article and declare no conflicts of interest.

Data AvailabilityAll data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article itself.

Received on Septemeber 27, 2025

Final version presented on October 6, 2025

Approved on October 7, 2025

Associated Editor: Lygia Vanderlei

; Silvia Lourdes Loreto Faquini2

; Silvia Lourdes Loreto Faquini2 ; Gláucia Virgínia de Queiroz Lins Guerra3

; Gláucia Virgínia de Queiroz Lins Guerra3 ; Alex Sandro Rolland Souza4

; Alex Sandro Rolland Souza4