ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: this study aimed to explore, from a maternal perspective, the experiences of Brazilian women regarding prenatal care, childbirth, and immediate postpartum period, including the associated feelings and emotions.

METHODS: a qualitative phenomenological study was conducted with six women, aged 18 years or older, who were in the third trimester of pregnancy during the first part of the study, regardless of parity, and who received care in both public and private healthcare institutions. Semi-structured online interviews were conducted during pregnancy and after birth (30-45 days). Data were analyzed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA).

RESULTS: the findings strongly indicate that perceptions and emotions regarding pregnancy and childbirth varied widely across participants. Common anticipatory feelings included fear, curiosity, and anxiety. Participants who reported negative maternity care experiences expressed feelings of apprehension and stress, whereas positive experiences fostered confidence and peace of mind regarding childbirth.

CONCLUSION: the findings highlight the diverse range of perceptions and emotions during pregnancy, childbirth and immediate postpartum among women in Brazil. The study

Keywords:

Pregnancy, Childbirth, Maternal mental health, Experience, Phenomenology

IntroductionThe transition to motherhood entails a complex interplay of expectations, emotional experiences, and demands, often requiring a reorganization of women's representational world.

1-3 Being pregnant and having a baby is a transitional phase marked by significant physical and psychological changes, which may also be accompanied by particular emotional challenges,

1,3,4 emotional fragility, and physical discomfort.

2While this transitional period can be experienced positively, it may also lead to anxiety and stress for some women.

2,3 Therefore, when evaluating women's individual experience of pregnancy, the impact of prenatal care is important to consider. Research findings indicate that women emphasize the significance of feeling respected and heard during prenatal care, highlighting its importance in shaping their views on the quality of care received.

5,6 Furthermore, reproductive health promotion not only improves pregnancy outcomes, reduces concurrent diseases, and enhances self-efficacy, but also diminishes the fear and anxiety associated with childbirth.

7,8 Similarly, the World Health Organization (WHO) underscores the significance of the woman's relationship with her maternity care providers in fostering a positive childbirth experience.

7A positive birth experience can provide women with feelings of satisfaction and empowerment, consequently contributing to their psychosocial well-being.

9-11 The degree to which childbirth diverges from the expected birth, may affect women's long-term psychosocial well-being.

12,13 A review of prospective studies showed that a mismatch between birth expectations and experiences is associated with lower birth satisfaction and an increased risk of developing postnatal Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

9. Moreover, Seefeld

et al.

14 suggest that a woman's expectation of her birth may be as important for her birth evaluation as the course of labor and medical interventions.

Initiatives to enhance care during labor, childbirth, and postpartum, focused on appropriate technology use and social mobilization have sought to reverse a Brazilian model historically characterized by excessive obstetric interventions.

15 The quality of intrapartum caregiver interactions has been highlighted as one of the main influences on women's emotional experience during labor and birth.

16-18 Evidence of the occurrence of disrespectful and violent practices experienced by women in obstetric care facilities, particularly during childbirth, is substantial, with little disagreement in the literature.

19,20 In 2019, a systematic review of 18 studies in Latin America reported a 43% prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth

21, phenomena collectively defined as of obstetric violence (OV). The term refers to any disrespectful, abusive, and dehumanizing treatment that women may experience from healthcare professionals during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period.

20 It also encompasses the appropriation of women's bodies and reproductive processes through excessive medicalization and the pathologization of natural functions, which subsequently leads to a loss of autonomy.

20 Such experiences can lead to physical and psychological illnesses. Consequently, obstetric care should be patient-centered, enabling women to express themselves freely and receive attention, clarification, respect, and empathy.

22Given this context, childbirth is a significant emotional event whose consequences can profoundly impact maternal mental health. Obstetric violence is known to occur in certain contexts and may significantly affect women's postnatal mental health. Although there is growing international interest in this topic, the paucity of national qualitative studies, particularly those that center women's own voices and subjective experiences, underscores the need for further investigation of these issues. This gap highlights the need to better understand Brazilian women's childbirth experiences from their own perspectives. Therefore, this study aims to explore women's perceptions of the childbirth experience, as well as their feelings and emotions during pregnancy, labor, and birth.

MethodsA qualitative interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA)

23 study was conducted with six women, aged 18 years or older, who were in their third trimester of pregnancy during the initial phase of the study. All participants provided written informed consent, and eligibility included pregnant women regardless of parity. Interviews were conducted during pregnancy (mean of 35.5 weeks' gestation) and in the postpartum period (mean of four weeks post-birth). No exclusion criteria were applied regarding the planned mode of delivery (e.g., vaginal, cesarean section).

Recruitment was facilitated through a general call for participation disseminated across various social media channels (e.g., WhatsApp, Facebook). A convenience sampling approach was employed, whereby participants were selected based on their availability, willingness to participate, and accessibility via social media platforms. Upon agreeing to participate in the study, participants completed an online screening questionnaire, which included age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education level, and the expected date of delivery to determine participants' gestational period. The primary investigator then contacted these women directly by email to schedule the prenatal interview. Following the first interview, the researcher would ask whether the participant knew any pregnant women who would be willing to participate in the study (snowball sampling technique).

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted remotely with participants using online video calls by the primary investigator throughout May and August 2022. The primary researcher conducted two online semi-structured sessions with each participant – one during the third trimester of pregnancy, and the other 30-45 days after postpartum. In the prenatal interview women were encouraged to share their feelings about pregnancy, their health care experiences, and their expectations for childbirth. For the postnatal interview, women shared detailed accounts of their views and experiences of childbirth. The sessions were audio-recorded and carried out via a videoconferencing platform e.g. Google Meet. They were conducted individually and lasted approximately 40 to 80 minutes each, with duration varying according to the depth and complexity of the participants' experiences. In the event of experiencing emotional discomfort during or subsequent to the application of the instruments, participants were offered support and brief intervention from the research laboratory professionals, as explicitly stated in the informed consent form. Field notes capturing reflections on participants' non-verbal communication were taken during and after sessions to complement transcripts, guide theme development, and support reflexivity in line with IPA principles.

23 Notes were revisited to ensure interpretations included spoken and interactional nuances. All sessions were transcribed.

A phenomenological approach was adopted to explore participants' lived experiences and how those experiences are perceived and manifest in consciousness. Consistent with this theoretical approach, a special interest is given to events that take place on a particular significance for people when they disrupt the everyday flow of lived events.

23 Following the methodology prescribed by Smith

et al.,

23 Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) is committed to the examining how people make sense of their major life events. Its focus on the convergence and divergence of these occurrences, along with its goal of providing a detailed and nuanced analysis of the lived experiences of a small group of participants. It is concerned with how a phenomenon appears, and aims to explore personal perspectives before moving to general claims.

23All interviews were originally conducted in the participants' native language (Portuguese) and subsequently translated into English by the first author, with the English transcripts serving as the language for coding and analysis. To maintain confidentiality, pseudonyms were assigned to each participant. Analysis was conducted by the principal investigator, who acted as the sole coder. Two supervisors (one native English speaker and one Portuguese native speaker) were consulted throughout the process to ensure rigor and adherence to the methodology.

Transcriptions underwent several iterative readings, with the researcher noting interesting or significant aspects of the respondent's statements. Initial coding yielded personal themes for each participant, which were then collated to form thematic groups across all participants. Through further analysis, these thematic groups were refined into the seven overarching themes that comprise the study's findings. Regular meetings were held with the supervisors to discuss any potential biases and ensure the integrity of the research process. Ethical approval was obtained from the Federal University of São Carlos Research Ethics Committee prior to conducting the research (CEAAE number omitted to protect author anonymity).

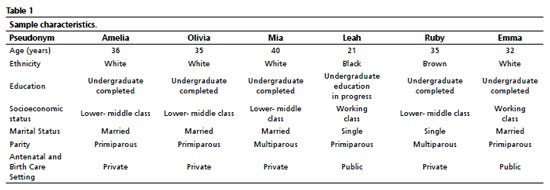

Results and DiscussionFourteen Brazilian women expressed interest in participating and six met the inclusion criteria. No participants dropped out. Sample Characteristics are described in Table 1. The sample consisted of six participants recruited from three different regions of Brazil: the majority (n=4) were from the Southeast, one was from the South, and one was from the Northeast. Among the multiparous participants, both were in their second pregnancy; however, and one had experienced a previous perinatal loss (Mia). Regarding mode of delivery, two of the six births were vaginal - (Leah and Emma), whereas four were cesarean sections.

Analysis of the interviews (conducted both pre- and postpartum) generated seven main themes (Table 2). Four themes emerged from the antenatal period, while three were generated from the postnatal interviews. Together, these themes described how participants made sense of their pregnancy and childbirth experiences, and the emotions involved, from their dual antenatal and postnatal perspectives. Although the intersection of race/ethnicity in reproductive health is recognized,

24 the relative homogeneity of this sample — mostly White, educated, partnered, and insured — likely contributed to shared perceptions of childbirth stressors. Omowale

et al.,

25 similarly found that Black and White women reported common pregnancy stressors, including partner issues, childcare, and finances, though some varied by race and education.

1. "In fact I think I'm beautiful" : How does it feel for one to be pregnantParticipants described what it meant for them to be pregnant in many ways. The majority expressed positive feelings and thoughts about being pregnant (n=4). Thoughts were considered to be contents that expressed the participants' interpretations, evaluations, or beliefs about themselves, others, and the world. Feelings were understood as the subjective experiences resulting from emotional activation (e.g., sadness, anger). For them, pregnancy was seen as enjoyable, desired, calm, and not disruptive to their lives. The amount of pregnancy symptoms and other's reactions to their pregnancy were associated with how enjoyable it was for them. Three participants made direct statements appreciating the special treatment received during pregnancy. For example, Mia. said:

Ah, it's very nice, everyone likes pregnant women. Treats her well, gives her presents…For Emma.: the joy of being pregnant went beyond the special treatment, relating instead to an increase of her self-esteem and the fact that she barely noticed being pregnant:

I forget that I'm pregnant. In fact, I think I'm beautiful (laughs)...I love being pregnant.In addition to the intensity of the symptoms experienced, the subjectivity of pregnancy experiences may also relate to the individual's emotional preparedness for the event. The two highlighted excerpts, which reflect the greatest sense of fulfillment within the participants' accounts in this study, originate from those with previous conception challenges—such as Mia, who had a pregnancy loss, and Emma, who underwent in vitro fertilization.

Pregnancy can only be interpreted within the context of each pregnant woman's personal history. Therefore, each woman's experience of this period is unique.

26 While for four participants being pregnant was associated with joy, for two of them, pregnancy was marked by changes and challenges that affected their emotions. For example, Amelia highlighted how she did not enjoy the changes in her body; the unpleasant feelings of guilt and restrictions regarding dietary intake and physical mobility:

It's not cool, there's a lot of transformation in the body, then it gets too heavy, I can't bend down to pick something up, many things you can't do.

But, like, (...) in general, it's not nice for me. I didn't like the experience (..) It has been a very different experience from anything I've ever experienced. An experience of great deprivation (...) Every time you go for an exam, you think "wow, if he has something, it's because I didn't eat right", you know? Everything is your responsibility. (...) I hated that part.

Conversely, Leah found her limited internal awareness of the pregnancy to be rather unpleasant, as it presented difficulties in comprehending and articulating her own experience. Together with the unexpectedness of her pregnancy, she emphasized it as being complicated:

It's complicated, because you create these... number of plans… pregnancy comes and you have to rethink everything, (...) it's a very uncertain scenario (...) I don't know. Sometimes I don't think much about it ... I don't feel that I'm pregnant.

Pregnancy is a period of intense psychosocial and emotional transformations, during which the woman undergoes a process of self-discovery and assumes the role of motherhood.

1 It's a complex and multidimensional experience that directly influences a woman's self-image and self-esteem, her relationships and behaviors, and evokes conflicting emotions such as happiness, fulfillment, fear, insecurity, tension, and anxiety.

42. "That's my greatest fear": Childbirth out of one's control In the present study, anticipatory feelings – such as fear, curiosity and concern – regarding the upcoming experience of childbirth were commonly presented in the sense of stepping into the unknown, suggesting a mixture of apprehension and excitement. For example, when describing her birth plan, Mia pointed out her concern of environmental influence on the normal birth outcome:

The idea is to have the beginning of labor here... getting there almost to birth. I know that, many times, with this change of environment, the labor, (...) it stops, right? (...) but I will try to concentrate, think only of myself, the baby (...).

For Emma, her concern was directed toward the possibility of giving birth to her baby in a hospital she strongly disliked:

I keep imagining where I'm going to be, who I'm going to be with, in case my water breaks, that's my biggest concern ... I don't like that hospital. Actually, it's not that I don't like it, but normally, when someone gets sick there, they always die (laughs)...I would only go there if, God forbid, I feel immense pain.

The significant presence of anticipation is also linked to the fact that five out of six participants in the study were nulliparous women. This finding aligns with previous reference, which reported that nulliparous women may experience greater fear than parous women before birth.

27For three of the participants, the fear was directed at the possibility of going through obstetric violence, as it was emphasized by Leah as one of her greatest concerns:

My big fear is the issue of obstetric violence (...) I think my body will know what it has to do, feeling pain does not worry me so much, but the issue of suffering violence is a lot in my head (…) if they forget something inside me. I think that's the biggest fear. I don't think so, it's my greatest fear.

This is consistent with documented statistics reporting high rates of obstetric violence in Brazil,

28 and may reflect the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, such as their high level of education and access to discussions and information about OV. Along with preparing themselves physically and psychologically, both Amelia and Emma described studying their rights as a coping strategy to address the fear of obstetric violence.

A: I studied what they can't do, what I can refuse, and I started to feel more calm. I went from a big fear that I had at the beginning of pregnancy to something more conscious now. It's what I chose. I know what can be done and what can't, and I'm calmer.

E: If they need to cut or do some procedure, will the doctor really ask the mother or father if it is ok (...)? There are people who simply think it's right and do it. (...) I'm not that scared, but I also know what my rights might be.

This highlights the importance of research on obstetric violence extending beyond the confines of the academic field and effectively reach the women who will be using maternity services, as it presents a potential opportunity for women to better comprehend their rights and prevent obstetric violence.

22It is worth noting that, in this study, the presence of anxiety and curiosity reflected a desire for the anticipated event to occur soon. In contrast, prior childbirth experience seemed to mitigate fear of childbirth:

The first time I was a little more fearful. It's different, totally different in that regard… I'm calm from the start (Ruby).3. Reaching the childbirth milestoneAn important feature of participants' reports was the appreciation and expectation of vaginal delivery for most of them. For some, the prospect of a cesarean section was, at times, related to fear and the feeling of giving up. When asked what they were afraid of, Olivia and Amelia described:

O: giving up, not being able to handle it. Saying "let's go for a cesarean section, because it's easier". In quotes, because they say the recovery is slower. I think I'm afraid of that.

A: I'm afraid of 2 things. Of not being able to stand the pain, and going through all of that stuff. Can't handle the pain, have anesthesia, anesthesia makes the baby's heartbeat weaker and go to the cesarean section. You know this combo?

Here, Amelia indicates that she actively avoided the thought of a cesarean section, choosing not to mention it in her birth plan:

I didn't include it because I didn't want to think about it too much (laughs) (...) only in case of an emergency (…) I don't like to think about it too much. I know there's also a huge list of things you can put in for the baby to come to you, but I didn't want to process that part.

For Ruby, the central focus was not necessarily vaginal delivery, but the ability to wait for the onset of labor, an experience she missed in her previous childbirth:

In this second pregnancy she [baby] is sitting down, but I wanted something to happen, signs of her, of her moment (laughs). I wanted to wait until the due date limit to see if she could get into labor, but so far not.Some participants also described sustained efforts to enable their desired birth experience. Three participants chose to hire a private maternity care team, believing this offered a better chance of pursuing a vaginal and humanized delivery in these circumstances:

Olivia: As I want a normal delivery, a humanized delivery, (...) I'm investing, both my doctors (...) are private doctors. Usually insurances' doctors don't have this patience, (...) this care.

Attending a number of appointments while preparing their body for birth experience were also cited as a way of physically preparing for childbirth.

4. "Now I'm laughing but at the time it was bizarre": antenatal healthcare experiencesFindings add to the growing evidence that women's relationship with their maternity care providers is central to a positive childbirth experience.

16-18 Antenatal healthcare experience played an important role in participants' feelings and emotions regarding childbirth, as they worried they might face the same challenges during labor and birth. Three participants described going through at least one difficult and uncomfortable prenatal appointment, which left them apprehensive, discouraged, and wishing for a more attentive care, as illustrated below:

Ruby: You sometimes expect a little more welcome, a conversation, and the professional is extremely objective, you know? Lacks a little of that greeting, (...) of letting you talk a little more about what you are feeling (…) I wanted the professionals to be more humanized, to listen to us a little, to believe. There are many, I know, but in my two [pregnancies] I didn't have the opportunity to experience it.

Amelia: In the last one I got a really shitty doctor, you know? He said some nonsense, these very old doctors, who think they are free to say anything to you, it was an unpleasant experience…Now I'm laughing, but at the time it was bizarre… I left apprehensive, a little scared, more sensitive. I thought "imagine if I get a shitty doctor like that at the time of delivery"

Leah: I don't have anything positive to say (...). It is very embarrassing to go there. It takes a long time, the doctor smells like cigarettes, it discourages you a lot.

These feelings and experiences were shared regardless of the type of institution—whether public or private. Conversely, experiencing positive and respectful healthcare provided peace of mind regarding childbirth, as Ruby reported finding comfort towards her decision of scheduling a cesarean when given the opportunity to consult with a professional who was considerate of her needs and feelings.

5. "Actually, it was nothing like I planned": Expectations versus reality during childbirthChildbirth brings relevant emotional experiences for women, given that, during labor, the anxiety experienced throughout pregnancy confirms or not the hopes and fears associated with it.

29 In the current study, results showed that the labor experiences of the majority of mothers differed from what they had anticipated, either in relation to unexpected signs of labor or unexpected outcomes. Most emphatically recognized that, at some point their childbirth, diverged from what they had planned. The impact of these unexpected events was clearly important for Leah:

It was so (…) unexpected. I knew it would be, but not that day, (…) I think that's the point. It got completely out of my control.

The sense of it being different from what was expected can also be seen in relation to women's reaction to labor. In this case, Mia and Leah did not follow some of the strategies they had studied and planned to put in practice during childbirth, such as eating high-calorie food to endure labor (Mia) or the pelvic floor training (Leah).

A significant unmet expectation in this study was the necessity of a cesarean section when a vaginal delivery was desired. They described their moment of acceptance:

Olivia: There was a moment when he left me alone, the whole team(…) I mentalized a lot and I think it was a moment that I accepted it (...) I was already kind of like "it's fine if I have to go for cesarean", you know?

Mia: I said "hey guys, (…) I don't want to feel more pain than what I'm feeling and I don't want to stay like this (gets emotional) (...) my dream was something that I could, I don't know, deal with".

Unexpected outcomes were perceived by some as a failure, which resulted in frustration and guilt, especially in cases of unplanned cesarean. This is consistent with Kjerulff and Brubaker's

30 prospective cohort study, where women who had unplanned cesarean were more likely to report feeling disappointed, upset, sad, angry, and like a failure, in comparison to women who delivered vaginally or by planned cesarean. In the present study, the cesarean was sometimes framed as a reason to question participants' maternity capacity. For example, Amelia stated:

"I can't fail at breastfeeding; I've already failed at childbirth," and Olivia shared:

"What kind of mother will I be for my daughter, if I didn't even do the birth I had planned?". This suggests that certain childbirth outcomes may lead women to feel guilty and affect their maternal self-perception.

However, several coping strategies for managing frustrated expectations were also apparent in the interviews. These included knowing they had done everything within their reach and maintaining faith that everything happened as it was supposed to were some highlighted coping strategies in participants' reports. Notably, these strategies were facilitated for those participants who had access to private healthcare.

Documented results draw attention to the importance of prenatal care to encompass the subjective experience of childbirth, addressing women's expectations and beliefs, and adequately preparing them for various f childbirth scenarios. Understanding this variability is crucial for healthcare providers to cater to the specific needs and experiences of each woman, thereby optimizing both maternal and infant health outcomes. Fulfilled expectations and a perception of control are essential to feeling satisfied and empowered during childbirth.

10,11,146. "I'm prepared, it's time": What comes to mind during childbirthThe experience of labor and childbirth evoked a range of thoughts and feelings in participants. While exhaustion was a common state for most of them, positive thoughts were also described as coping strategies utilized during childbirth. The following extract from Mia demonstrates how she tried to remind herself of the physical and emotional support surrounding her:

It's good that I have support, both from [her partner] and from the nurses. I thought, "It's good that I'm in a hospital that I trust, that I know everything is right". I stayed in that positivity…So, (...) "I'm prepared".

In contrast, for two participants, the perception of the hospital stay, physical demands, and emotional intensity of childbirth was shaped by pain and healthcare-related stress, as Leah describes below:

Overall, it wasn't good (laughs). In several aspects, from the beginning, when I arrived (...) having to stay in the hospital (...) It was very exhausting. The experience was not good. There were several moments when I was getting tired of being there.

Consistent with pregnancy,

24 the subjectivity of childbirth must be interpreted within its contextual framework. In this study, participants' confidence in giving birth was influenced by socioeconomic factors—such as being able to afford insurance or invest in a private care team—and by the presence of a supportive partner.

7. Maternity care's impact on one's emotion during childbirthParticipants indicated that healthcare and the delivery environment exert a strong influence on their emotional state during childbirth. Leah, for example, was emphatic in her view of how the stress and anxiety she felt during labor was directly caused by healthcare practices:

For the touch exam, one comes, then another person comes, says something different. In the end you're talking to 500 people and no one is actually your doctor. (...) In the end you don't have any information. That ends up bringing such anxiety.

(...) When I got there so many things happened, I was already completely unmotivated.

Similarly, Amelia also highlighted her desire for greater privacy during childbirth, adding that an excessive number of professionals present acted as a distraction during labor:

This thing of many professionals coming in all the time, I think that I would like it to have been different. (...) It distracted me a lot. Every time someone would come in and introduce themselves, then you kind of get out of the moment there.

The lack of privacy, a common complaint in delivery rooms, was again mentioned by both a participant assisted by public services (Leah) and a participant assisted by a private service (Amelia). Although the high turnover of staff and the presence of numerous professionals were more strongly emphasized by Leah. As these comments indicate, the type and quality of healthcare provided during childbirth can influence women's emotions during the process of giving birth,

7,18 a factor that participants believed impacted the overall outcomes of childbirth. By recognizing and respecting women's subjective experiences – such as involving women in decision-making, actively listening to their concerns, offering emotional support, and providing clear and accurate information – healthcare providers have the opportunity to promote their well-being during this transformative period.

7,10,11,18Final considerations The maternal experience, across its various stages, emerges as a dynamic field of meaning-making and negotiation between personal expectations, social norms, and institutional practices. Through the lens of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), we explored how women attribute meaning to their experiences of pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period—particularly regarding their encounters (and misalignments) with healthcare services.

The results strongly support the notion that pregnancy's perception and emotions regarding childbirth vary widely among individuals. The narratives highlight the critical importance of woman-centered obstetric care that is highly attuned to individual subjectivities and sociocultural contexts. When care is mediated by active listening, relational connection, and respect, it holds the potential to strengthen women's agency and reduce iatrogenesis. Conversely, when characterized by silencing and unnecessary interventions, care itself may become a source of suffering.

Given the scarcity of national studies on this subject, this study highlights the need for further in-depth research to explore Brazilian women's perinatal experiences and to inform culturally sensitive, evidence-based practices. Qualitative research can contribute valuably to perinatal psychology by documenting detailed processes occurring in particular individuals, thus offering valuable insights into the complexities of perinatal experiences. Future research should expand upon these findings using more diverse samples and settings, with the goal of informing strategies that enhance assistance to the broader population of women across varying regions and social backgrounds.

Some limitations must be considered for the present study. Participants' experiences were shaped by the sample's homogeneity, who were mostly White, educated, partnered, and insured. Access to private care and partner support influenced how they managed challenges.

Furthermore, details on the gestational period and attendance to prenatal care were collected via participants' self-report. A minor limitation of the study is that no formal documentation was requested to verify this data. Although the small sample and homogeneity are consistent with IPA methodology, semi-structured interviews did not strictly follow an IPA interview guide, and some questions could have been more open-ended, potentially allowing more detailed or nuanced themes to emerge from data.

By shedding light on women's lived experiences within the Brazilian healthcare context, this study underscores the importance of qualitative research centered on service users' perspectives during the perinatal period. It can, therefore, contribute to improving the quality of perinatal care and guiding public health policies aimed at more humane and equitable maternity care. Findings reveal how perceptions of disrespectful or non-empathetic care point to gaps in emotional support, communication, and autonomy, thus indicating areas for improvement in professional training and protocols. These insights may guide interventions that promote respectful, individualized care and underscore the pressing need for national data on childbirth quality, obstetric violence, and women's overall experiences in maternity services.

References1. Lima MM, Andrade Leal C, Costa R, Zampieri MD, Roque AT, Custódio ZA. Gestação em tempos de pandemia: percepção de mulheres. Rev Cient Enf (Recien). 2021 Mar; 11 (33): 107-16.

2. McCarthy M, Houghton C, Matvienko-Sikar K. Women's experiences and perceptions of anxiety and stress during the perinatal period: a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21 (1): 1-12.

3. Matvienko-Sikar K, Flannery C, Redsell S, Hayes C, Kearney PM, Huizink A. Effects of interventions for women and their partners to reduce or prevent stress and anxiety: a systematic review. Women Birth. 2021; 34 (2): e97-e117.

4. Ribeiro Filho JF, Luz VL, Sousa AS, Silva GL, Feitosa VC, Almeida MF. Contribuição do pré-natal para o parto normal na concepção do enfermeiro da estratégia saúde da família. Rev Interdiscipl. 2016; 9 (1): 161-70.

5. Santos Chaves I, Campos Verdes Rodrigues ID, Alves Cartaxo Freitas CK, Claudino Barreiro MD. Prenatal consultation of nursing: satisfaction of pregnant women. Rev Pesqui Cuid Fundam. 2020 Jan; 12 (1).

6. Sátiro LS, Santos AM, Smith AC, Cruz GK, Silva FC, Salvador PT. Expectativas e satisfação das gestantes com o pré-natal de uma unidade básica de saúde de Natal, Brasil: estudo transversal. Esc Anna Nery. 2024; 28: e20240037.

7. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: WHO; 2016. 152 p. [access in 2024 Jul 7]. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892415499128. Athinaidou AM, Vounatsou E, Pappa I, Harizopoulou VC, Sarantaki A. Influence of antenatal education on birth outcomes: a systematic review focusing on primiparous women. Cureus. 2024 Jul; 16 (7): e64508.

9. Webb R, Ayers S, Bogaerts A, Jeličić L, Pawlicka P, Van Haeken S,

et al. When birth is not as expected: a systematic review of the impact of a mismatch between expectations and experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21 (1): 475.

10. Ďuríčeková B, Škodová Z, Bašková M. Satisfaction with childbirth and level of autonomy of women during the childbirth. Cent Eur J Nurs Midw. 2024 Dec; 15 (4): 2060-8.

11. Leinweber J, Fontein‐Kuipers Y, Karlsdottir SI, Ekström‐Bergström A, Nilsson C, Stramrood C,

et al. Developing a woman‐centered, inclusive definition of positive childbirth experiences: a discussion paper. Birth. 2023; 50 (2): 362-83.

12. Davies A, Larkin M, Willis L, Mampitiya N, Lynch M, Toolan M,

et al. A qualitative exploration of women's expectations of birth and knowledge of birth interventions following antenatal education. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024 Dec; 24 (1): 875.

13. Preis H, Lobel M, Benyamini Y. Between expectancy and experience: testing a model of childbirth satisfaction. Psychol Women Q. 2019; 43 (1): 105-17.

14. Seefeld L, Weise V, Kopp M, Knappe S, Garthus-Niegel S. Birth experience mediates the association between fear of childbirth and mother-child-bonding up to 14 months postpartum: findings from the prospective cohort study DREAM. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 12 (776922): 1-12.

15. Aguiar CD, Lopes GA, Bussadori JC, Leister N, Riesco ML, Alonso BD. Modelo de atenção em centros de parto normal peri-hospitalares brasileiros: uma revisão de escopo. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2025 Jan; 30: e09382023.

16. Leinweber J, Stramrood C. Improving birth experiences and provider interactions: expert opinion on critical links in maternity care. Eur J Midwifery. 2024 Sep; 8.

17. Leinweber J, Fonstein-Kuipers Y, Thomson G, Karlsdottis S, Nilsson C, Ekström-Bergström A,

et al. Developing a woman-centred, inclusive definition of traumatic childbirth experiences. In: 21

st International Normal Labour and Birth Research Conference; 2022; Denmark–Aarhus. 2022; 49 (4): 1-1.

18. Oladapo OT, Tunçalp Ö, Bonet M, Lawrie TA, Portela A, Downe S,

et al. WHO model of intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience: transforming care of women and babies for improved health and wellbeing. BJOG. 2018; 125 (8): 918.

19. Katz L, Amorim MM, Giordano JC, Bastos MH, Brilhante AV. Quem tem medo da violência obstétrica?. Rev Bras Saúde Mater Infant. 2020; 20: 623-6.

20. Williams CR, Jerez C, Klein K, Correa M, Belizán JM, Cormick G. Obstetric violence: a Latin American legal response to mistreatment during childbirth. BJOG. 2018; 125: 1208-11.

21. Tobasia-Hege C, Pinart M, Madeira S, Guedes A, Reveiz L, Valdez-Santiago R,

et al. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth and abortion in Latin America: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pan Am J Public Health. 2019; 43: e36.

22. Souza Rusch G, Silva Marrone VG, Santos Guimarães GK, Brito BF, Silva Santos LC, Borba MB,

et al. Violência obstétrica vivenciada por mulheres na hora do parto: uma revisão da literatura: Obstetric violence experienced by women during childbirth: a literature review. Braz J Health Rev. 2022 Oct; 5 (5): 20017-27.

23. Smith JA, Larkin M, Flowers P. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research. 2

nd ed. London: SAGE Publications; 2021.

24. Alvarenga AT, Souzas R. Mulheres negras e brancas e a maternidade: questões de gênero e raça no campo da saúde. ODEERE. 2017; 2 (3): 278-99.

25. Omowale SS, Gary-Webb TL, Wallace ML, Wallace JM, Rauktis ME, Eack SM,

et al. Stress during pregnancy: An ecological momentary assessment of stressors among Black and White women with implications for maternal health. Womens Health (Lond.). 2022; 18: 17455057221126808.

26. Castro AS, Lima GI, Ferreira TH. Os aspectos psicológicos da mulher: da gravidez ao puerpério. Ces Rev. 2019 Dec; 33 (2): 202-18.

27. Sanjari S, Chaman R, Salehin S, Goli S, Keramat A. Update on the Global Prevalence of Severe Fear of Childbirth in Low-Risk Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Women's Health Reprod Sci. 2022 Jan;10 (1).

28. Leite TH, Marques ES, Corrêa RG, Leal MD, Olegário BD, Costa RM,

et al. Epidemiologia da violência obstétrica: uma revisão narrativa do contexto brasileiro. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2024 Aug; 29: e12222023.

29. Cunha ACBD, Santos C, Gonçalves RM. Concepções sobre maternidade, parto e amamentação em grupo de gestantes. Arq Bras Psicol. 2012; 64 (1): 139-55.

30. Kjerulff KH, Brubaker LH. New mothers' feelings of disappointment and failure after cesarean delivery. Birth. 2018 Mar; 45 (1): 19-27.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (2022/01097-7) for the financial support.

Author's contributionVasconcelos Barros MV: conceptualization, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. D'Affonseca SM: conceptualization, supervision, and critical review of the manuscript. Ayers S: data analysis oversight, and critical review of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the article and declared no conflicts of interest.

Data AvailabilityAll datasets supporting the study are included in the article.

Received on December 18, 2024

Final version presented on September 29, 2025

Approved on October 13, 2025

Associated Editor: Aline Brilhante

; Sabrina Mazo D'Affonseca2

; Sabrina Mazo D'Affonseca2 ; Susan Ayers3

; Susan Ayers3