ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: the present study aims to carry out a cross-cultural adaptation of the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/ Experience Questionnaire Version B (WDEQ-B) into Brazilian Portuguese and apply it to a sample of Brazilian postpartum women, evaluating the prevalence of Fear of Childbirth (FoC) and possible associated factors.

METHODS: we conducted a cross-sectional study encompassing a process of translation and back-translation of the instrument followed by a pretesting phase.

RESULTS: we performed a cross-cultural adaptation of the WDEQ-B, with reasonable match from the original instrument and broadly comprehensible by our sample. 57 postpartum women were included, at three public maternity hospitals, finding a severe FoC prevalence of 10.6%. In addition, analyzing FoC and disruption between desired and actual delivery, a prevalence ratio of 10.8 (CI95%=1.3-87.7, p=0.026), was found.

CONCLUSION: the WDEQ-B was successfully adapted to the Brazilian Portuguese and showed to be a linguistic and culturally comprehensible research tool to analyze FoC among postpartum women in our population. Moreover, the study showed that disruption between desired and actual delivery mode might be associated with FoC occurrence.

Keywords:

Fear, Childbirth, Questionnaire, Cross-cultural adaptation, Postpartum women

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: o presente estudo objetiva realizar uma adaptação transcultural do Wijma Delivery Expectancy/ Experience Questionnaire versão B (WDEQ-B) para o português brasileiro e aplicá-lo numa amostra de puérperas brasileiras, avaliando a prevalência do medo do parto e possíveis fatores associados.

MÉTODOS: realizou-se um estudo transversal envolvendo um processo de tradução e retrotradução do instrumento seguido de uma fase de pré-teste.

RESULTADOS: foi realizada uma adaptação transcultural do WDEQ-B, com correspondência razoável com o instrumento original e amplamente compreensível pelas mulheres brasileiras. Foram incluídas 57 puérperas, em três maternidades públicas, encontrando-se uma prevalência de 10,6%. Além disso, analisando-se a relação entre medo do parto e discordância entre preferência de via de parto e parto atual, foi encontrada uma razão de prevalência de 10,8 (IC95%= 1,3 – 87,7, p=0,026).

CONCLUSÃO: o WDEQ-B foi adaptado com sucesso para o português brasileiro e se mostrou um instrumento de pesquisa linguisticamente e culturalmente compreensível para analisar o medo do parto. Além disso, o estudo mostrou que discordância entre preferência de via de parto e parto atual parece estar associada à maior ocorrência de medo severo do parto.

Palavras-chave:

Medo, Parto, Questionário, Adaptação transcultural, Puérperas

IntroductionFear of Childbirth, or FoC, is a very important clinical condition, affecting around 14% of pregnant women worldwide and presenting an increasing trend over the recent years

1. Severe FoC or tokophobia is defined as an irrational fear of the moment of the delivery and is related to several negative consequences for women, concept and family. Numerous studies have found an association between this condition and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), postpartum depression, anxiety disorders and poor filial maternal bond, thus its early diagnosis and proper intervention is essential for maternal mental health care.

2,3,4 Currently, the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire (WDEQ) is the most validated and recognized tool for FoC evaluation.

5The WDEQ was developed in 1998,

5 after ten years of study, intending to measure a construct of fear related to childbirth, both during pregnancy and after childbirth. The psychometric evaluation was designed by its application on 196 pregnant women, among eight other instruments, reaching a Chronbach’s α ≥ 0.87. The questionnaire contains 33 questions investigating feelings and thoughts that might occur regarding childbirth. The questions are answered on a Likert scale that varies from zero (extremely) to five (not at all). The final score varies from zero to 165 and it is determined by the summation of all responses, notwithstanding, the items which correspond to positive feelings (2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15, 19, 20, 24, 25, 27, 31) must be reversed for calculation.

5 The WDEQ showed to be a reliable, concrete and comprehensible instrument, being translated and validated to several languages, such as Japanese,

6 Malawi,

7 Turkish,

8 German,

9 Spanish

10 and Hindi,

11 to name a few.

Since the creation of the scale, several cutoff points have been suggested, currently the most accepted is 85, which implies the presence of severe fear of childbirth and recommends a wider investigation on these women. The establishment of this specific cutoff point was proposed by a longitudinal observational study with 106 women, aiming to find the optimal cut-off score referring to the DSM-5 Specific Phobia criteria as a gold standard. After applying psychometric questionnaires investigating depression, anxiety, and fear of childbirth, before and after the delivery moment, they presented the 85 cutoff point with a high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (93.8%) for detecting clinically relevant FoC.

3It is important to point out there has been an increasing number of publications on this matter in the last decades, mainly after 2000, reaching nearly a 30-time increase in volume, which also correlates with the time of WDEQ’s creation (1998). Nonetheless, according to a bibliometric analysis,

12 almost all these scientific works took place in European countries, paradoxically, countries with higher birth rates have not yet reached a significant number of studies in this field. The number of publications about FoC in Brazil in 2020 corresponds only to 4% of worldwide publications on the subject. Further, Brazil ranks as the second country in the world with the highest rate of cesarean sections (57%), and several studies have indicated that FoC contributes for many of these procedures.

13,14,15The cross-cultural adaptation’s process aims to reach equivalence between the original source and target versions of a questionnaire, looking at not only language but also cultural aspects. This process gives rise to a more confident instrument, considering it is being constructed for the use in a certain cultural context, specifically, likewise reduces bias and enhances study’s viability.

16The present study aims to carry out the cross-cultural adaptation of the WDEQ-B into Brazilian Portuguese and apply it to a sample of Brazilian postpartum women, evaluating the prevalence and possible associated factors.

MethodsThis study was conducted in Maceió, capital city of the state of Alagoas, located in the Northeast region of Brazil, on three healthcare facilities: one high-risk obstetric maternity and two low-risk obstetric services.

Primarily, our research group contacted the author of the original instrument asking for permission to the questionnaire’s translation, and we received his positive response and some directions for the procedure. The process of cross-cultural adaptation occurred in five steps, following the Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures,

16 comprising: translation, synthesis, back translation, expert committee review and pretesting.

The first step was the translation of the original scale to Brazilian Portuguese by two independent translators, L.L.B. who has a previous knowledge on FoC, and A.D.P.V.C., without previous clinical knowledge on this matter. Hence two versions were generated, T1 and T2, as depicted in the second column of Table 1.

On the second step, both translations were merged in one single version, named T12, and language discrepancies were solved after the analyses of two independent reviewers. Then, the third step, the back translation, took place, and two medicine students, P.H.N.S. and E.P.B.F., back translated the T12 version to Brazilian Portuguese, generating versions BT1 and BT2, as seen in the fourth column of Table 1. Both students who participate in this stage are researchers by the institutional program of scientific initiation scholarships at the Federal University of Alagoas and have English language expertise. The fourth step was the expert committee review, when all researchers dwell on the produced documents to reach a consensus over the deviations and construct a final version of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the WDEQ-B. At this stage, V.L.M.N. and M.L.M. were invited to compose the expert’s committee

, both have previous experience in the process of cross-cultural adaptation of research tools, as well as mastery of both Portuguese and English languages. The final version formed after the committee is depicted in the last column of Table 1.

The fifth and last step consisted of the experimental application of the instrument on 57 puerperal women, interviewed in the first 72 hours postpartum during their period of hospitalization. According to the utilized guideline, this step of the process should include at least 30 to 40 subjects, assessing different educational levels and a certain sample heterogeneity. Two other questionnaires were also applied, a questionnaire with basic obstetric and clinical information and the Brazilian version of the Social Support Scale of Medical Outcomes Study (MOS-SSS).

17The MOS-SSS was created in 1991, by interviewing 2987 patients with chronic disease, developing an objective, easily comprehensible, self-administered questionnaire, which evaluates the individual’s perception of social support.

17 The questionnaire was validated by its application in 4030 employees inserted in the

Pró Saúde study, in Brazil, showing high internal consistency levels (Chronbach’s α ≥0.83) and moderate item-scale correlation.

18 The inquiry is formed by 19 questions, answered in a Likert scale of five items: never, hardly ever, sometimes, almost always and always. The validated Brazilian scale covers three dimensions: positive social interaction/affective support (seven items); emotional/informational support (eight items); and material support (four items). The total score is achieved by the summation of all items, the higher the score, the greater the perception of social support. Commonly, the results are interpreted by distributing the sample in quartiles and using the 25

th quartile as the cut-off point, the same process is performed with each dimension, enabling a detailed analysis of the lack of perceived support.

18The data collected was inserted on an Excel spreadsheet. Formerly, the data was examined descriptively using STATA program version 16.0, utilizing the format of mean and standard deviation. T-tests were performed depicting a normal sample according to Shapiro-Wilk analyses, with a

p<0.001. The sample was categorized in two main groups, with and without severe FoC, according to the WDEQ’s score cutoff point of 85. The scores of the MOS-SSS were summed, and then dichotomized, using the first distribution quartile as a cutoff point.

18The two groups were then compared regarding the variables: perceived low social support, age, educational level, marital status, income, origin (capital city or countryside), obstetric risk, parity, preferred mode of delivery and actual mode of delivery. The definition of high or low obstetric risk was performed according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health High-Risk Pregnancy Manual.

19 The comparison between the groups was assessed by chi square analyses. The associations between the presence of severe FoC and the categorical variables were assessed by Poisson regression analyses, which generated prevalence ratios, with a 95% confidence interval.

This survey was submitted and approved by the local ethics and research committee of the Federal University of Alagoas (protocol number 58827122.4.1001.5013).

ResultsFirstly, two Brazilian Portuguese versions were held by two independent translators, as depicted in Table 1, and the construction of T12 took place. The answers to the questions are given in a Likert scale from 1 to 6 and at the end of both extremities a certain feeling or thought can be categorized as something in between of “extremely” and “not at all”. At the T12 version’s construction, it was decided to translate these expressions as “extremamente” and “nem um pouco”. The literal Portuguese translation of “not at all” would be the noun “nada”, however this expression is not commonly used in Brazilian Portuguese together with adjectives, thus we chose for a more informal and culturally used expression.

There was similar translation on most terms, except on items 6, 13, 16, 21 and 26 (Table 1). At item 6, “afraid” was translated as “assustadora” or “apavorada”. During the discussion, the root of the word “apavorada” was analyzed, “pavor” means great fear with astonishment or startle; while the word “assustadora” means simply: which causes fear. Therefore, we reached the consensus that the term “assustadora” brought the best interpretation of what women might feel during their childbirth. In the item 13 there was agreement that both terms “contente” and “satisfeita” were plausible substitutes for “glad”, however, “satisfeita” implies a broader feeling towards the birth experience, and therefore, was sustained. In item 16, the word “composed” was translated as “calma e serena” and “comportada”, it was interpreted that the author’s real intention was to express serenity in childbirth, and the word “serena” was elected. In item 21 the expression “longing for the child” was particularly challenging, and it was interpreted as two different feelings: “Saudade extrema do filho (medo de perder) o filho” and “ansiosa pela criança”. The expression “To long for something” involves a great desire or need for something; it is complex to make this translation for Brazilian Portuguese since we don’t have a similar expression that could be applicable in the childbirth context. Finally it was decided to sustain “extremo anseio de ter a criança”, aiming to express the mother´s great willingness to deliver her baby. The item 26 was also perplexing due to the unusual manner it was written in English “I dared to totally surrender control to my body”. The two translations were: “Eu duvidei a ponto de entregar todo o controle do meu corpo”; and “Deixei que o meu corpo tomasse o controle”. Our intention was to make the questionnaire more comprehensible for any educational level, thus, we simplified the expression as “Desisti totalmente de controlar meu corpo”.

After the construction of the T12 version the back translation was performed by P.H.N.S. and E.P.B.F. and the expert’s committee took place. The committee was formed by three experienced researchers in maternal mental health, who had conducted several studies about the effects of poor maternal mental health, and all the other researchers involved in the process. On most items, the back translation reached the original author’s words.

PretestingThe final version of the scale, presented at the last column of Table 1, was then applied in 57 participants, through oral interviews, on their first 72 hours postpartum period. The authors L.L.B, P.H.N.S. and E.P.B.F. approached the subjects during their hospitalization time and filled up the questionnaire through an online form. After each interview, subjects were asked if all words were comprehensible and if they had difficulty understanding the questions. The time needed to complete the whole questionnaire ranged from eight to 15 minutes.

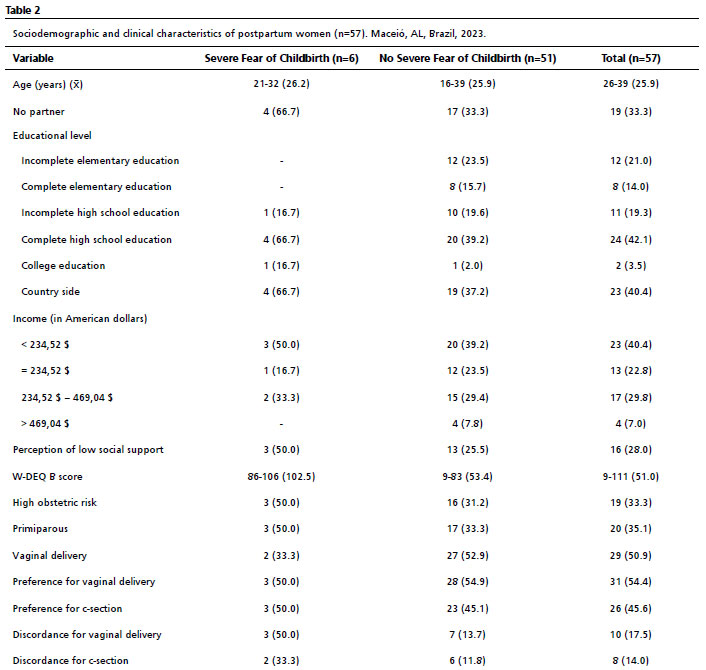

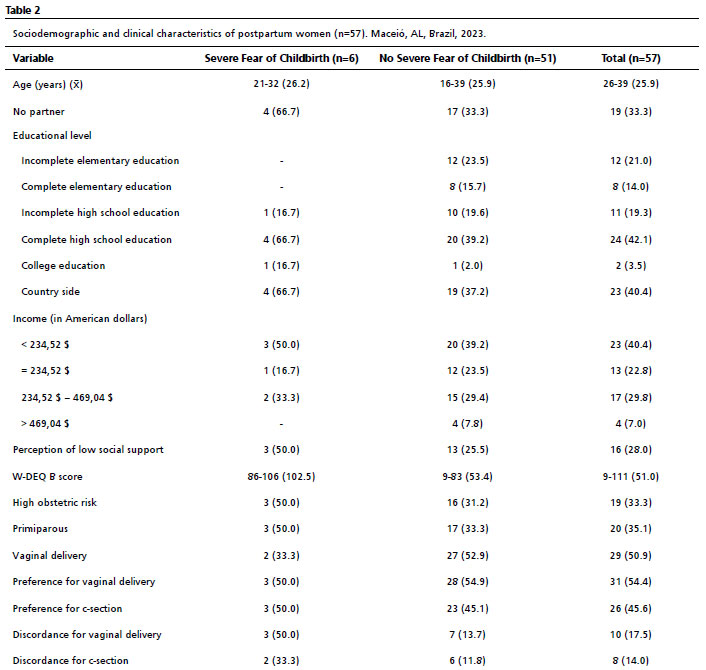

All the obtained descriptive data is depicted in Table 2. A sample of 57 women with different educational levels were included in this study: 12 with incomplete elementary education, eight with complete elementary education, 11 with incomplete high school education, 24 with complete high school education and two with higher education. The age of participants ranged from 16 to 39, with a mean of 25.9 (SD=5.8). The marital status prevalence was 66.7% (n=38) women with stable union or married and 33.3% (n=19) single. There was a prevalence of 35.1% primiparous women (n=20), and 33.3% were configured as high obstetric risk (n=19).

The average W-DEQ B score was 51 (SD=24.1), ranging from nine to 111. The prevalence of severe fear of childbirth was 10.2% (n=6), which corresponds to a W-DEQ B score superior or equal to 85. The percentage of vaginal birth and cesarean sections was 52.6% (n=30) and 47.3% (n=27) respectively and both groups had an equal distribution for severe FoC (Three subjects in each group). The preferred mode of delivery was 45.61% (n=26) for cesarean section and 54.39% (n=31) for vaginal birth. Nonetheless, there was a disruption between preferred mode of delivery and actual delivery in 18 (31.6%) of the participants. Of these, ten women desired a vaginal birth but underwent a C-section and eight women preferred a C-section but had vaginal delivery.

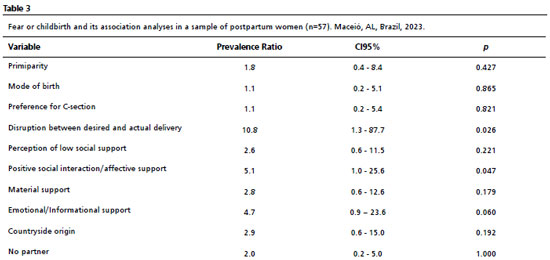

We performed the Poisson regression test evaluating the possible associations between severe FoC and other variables, as depicted in Table 3. Severe FoC and mode of birth was analyzed, finding a prevalence ratio of 1.1, whereas there was an equal distribution of C-section and vaginal birth among the group with severe FoC (three individuals each). Examining the relation between severe FoC and preference for C-section, the prevalence ratio found was also 1.1, since three women with FoC preferred vaginal birth, and three preferred C-section. Notwithstanding, evaluating the relation between severe fear of childbirth and disruption between preferred mode of delivery and current childbirth, we found a positive statistically significant association.

Perception of low social support was not significantly associated with severe FoC. Analyzing each dimension of social support separately, we found a positive statistically significant association with the positive social interaction/affective support dimension.

All six participants with severe FoC were aged lower than 35 years and had incomplete high school educational level or higher.

DiscussionFoC is a rising research field, which urges for further investigation in emerging countries, especially in Brazil, where there is no international validated research tool. The vaginal and cesarean section rates found in this study assemble the numbers found in the Northeast of Brazil, depicting an appropriate sample for testing of this research instrument.

20 We also have found that Brazilian women have a different perception of birth regarding delivery mode, since the preference for vaginal birth or C-section was almost the same, with a slight inclination to the vaginal birth (54.9%).

The only Brazilian study, to this date, which investigated FoC using the WDEQ conducted analyzing 67 pregnant women who attended prenatal care in Santos, São Paulo. The applied questionnaire was the “

Questionário sobre o Medo Percebido do Parto (QMPP)”, a European Portuguese version of WDEQ-A, validated for application in Portuguese women. The prevalence of severe FoC was 31.4%, considering a score equal or higher than 85. They also found higher scores in older women: the mean age of the group with severe fear of childbirth was 30, while in the group without severe fear of childbirth was 25, but there was no statistical difference between the groups. Further, a positive relation between severe fear of childbirth and marital status of married or stable union was found, with a

p=0.017. The study was a pioneer in this matter in Brazil, nonetheless, the research tool utilized was not created or adapted for application in Brazilian settings, and therefore the results must be interpreted with caution.

21The FoC postpartum rate found in this study, 10.5%, assembles with the global mean of 14% (3.4-43%).

1 FoC worldwide prevalence was estimated through a meta-analysis conducted in 2017, with the inclusion of 29 studies, of which 19 utilized the W-DEQ as the main research tool. Nonetheless, significant heterogeneity was observed (I

2 = 99.25%) and all studies were conducted during the prenatal period, accounting for 853,988 pregnant women. There is no meta-analysis, to this date, which focuses solely on FoC after childbirth.

Our study findings suggested that women with disruption between preference of delivery mode and actual delivery mode tend to have severe FoC. This was also suggested by another work, by the analyses of the childbirth experience in 496 Swedish primiparous women.

22 The aim of the study was to investigate the differences between childbirth experience in women who had an elective C-section and other types of delivery, using the WDEQ-A at prenatal period and WDEQ-B, applied three months after delivery. According to the study, there were more negative childbirth experiences among women who had planned to a natural childbirth but had an emergency cesarean or an assisted vaginal delivery, compared to the ones who had elective C-section or spontaneous vaginal delivery (

p<0.001 in ANOVA tests comparing the groups). In the present study, it was observed an association with severe FoC on women who did not achieve their desired delivery mode. Thus, women who have frustrated experiences of childbirth may be at a higher risk of developing severe FoC and must have greater postnatal emotional and psychological support.

A study conducted by Mortazavi and Mehrabadi,

23 assessed 662 puerperal Iranian women, finding a severe FoC rate of 21.1%, using also a W-DEQ B cutoff point of 85. Likewise, they revealed that women with lower educational levels had higher FoC levels, which differs from our study, in which the six women with severe FoC were no less than graduated from high school. Regarding age, women < 30 had higher levels of severe FoC (

AdjustOR=0.048,

p=1.428), which was similar to our study in which all women with severe FoC were aged lower than 35 years. The authors also examined variables regarding women’s support, finding that low level of satisfaction with marital/sexual relationship (OR=2.066,

p=0.018) and low level of satisfaction with pregnancy (OR=9.0,

p<0.001) predicted severe FoC, however, unlike the present study, there was no validated questionnaire to examine those variables.

23Our study used a validated questionnaire, to assess the perception of social support in puerperal women, in a broader definition and demonstrated that it can be a risk factor for FoC development, although we have found no statistical significance in our analysis. When analyzing the dimensions of social support it was found that the dimension with a greater correlation with severe FoC development was positive social interaction/affective dimension, reaching a

p value compatible with statistical significance. This finding was predictable, since several studies show that people who participate in social activities tend to be less vulnerable to isolation, stress and health conditions.

17 Therefore, social support seems to play an important role in women’s mental health and FoC development, being a crucial aspect to be further investigated, and assessed, in the Brazilian population.

The study accomplished developing a Brazilian Portuguese version of an important research tool, widely utilized in assessing FoC. The pretesting period demonstrated good comprehensibility, showing to be a linguistically and culturally suitable instrument. It is important to note that our sample was composed by Unified Health System (SUS – Portuguese acronym) users, who commonly have lower educational level and income, suggesting being comprehensible in all settings. Moreover our pretesting’s results show that Brazilian women tend to have higher FoC rates when inserted in higher educational levels and aged lower than 35 years, since the entire sample with severe FoC had these characteristics, although we could not point out possible causes for these findings. In addition, disruption between preferred delivery mode and current childbirth was positively associated with severe FoC, suggesting this population could be at higher risk of experiencing a more negative childbirth experience. These findings highlight the importance of more Brazilian studies regarding FoC, with broader samples, to point out the cultural differences involved within our population’s particularities. Additionally, more studies applying our adapted research tool are needed to perform psychometric evaluations and questionnaire’s validation.

References1. O´Connell MA, Leahy-warren P, Khashan AS, Kenny LC, O´Neil SM. Worldwide prevalence of tocophobia in pregnant women: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017; 96 (8): 907–20.

2. Jomeen J, Martin CR, Jones C, Marshall C, Ayers S, Burt K,

et al. Tokophobia and fear of birth: a workshop consensus statement on current issues and recommendations for future research. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2021; 39 (1): 2–15.

3. Calderani E, Giardinelli L, Scannerini S, Arcabasso S, Compagno E, Petraglia F,

et al. Tocophobia in the DSM-5 era: Outcomes of a new cut-off analysis of the Wijma delivery expectancy / experience questionnaire based on clinical presentation. J Psychosom Res. 2019; 116 (November 2018): 37–43.

4. Challacombe FL, Nath S, Trevillion K, Pawlby S, Howard LM. Fear of childbirth during pregnancy: associations with observed mother-infant interactions and perceived bonding. Arch Women’s Mental Health. 2021; 24 (3): 483–92.

5. Wijma K, Wijma B, Zar M. Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; a new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. 1998; 19: 84–97.

6. Takegata M, Haruna M, Matsuzaki M, Shiraishi M, Murayama R, Okano T, Severinsson E. Translation and validation of the Japanese version of the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire version A. Nurs Health Sci. 2013; 15 (3): 326-32.

7. Khwepeya M, Lee GT, Chen SR, Kuo SY. Childbirth fear and related factors among pregnant and postpartum women in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18 (1): 1–10.

8. Korukcu O, Bulut O, Kukulu K. Psychometric Evaluation of the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire Version B. Health Care Women Int. 2016; 37 (5): 550-67.

9. König J. The German W-DEQ version B-Factor structure and prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms six weeks and one year after childbirth. Health Care Women Int. 2019; 40 (5): 581-96.

10. Roldán-Merino J, Ortega-Cejas CM, Lluch-Canut T, Farres-Tarafa M, Biurrun-Garrido A, Casas I,

et al. Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the “Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire” (W-DEQ-B). PLoS One. 2021; 16 (4): 1-12.

11. Jha P, Larsson M, Christensson K, Svanberg AS. Fear of childbirth and depressive symptoms among postnatal women: a cross-sectional survey from Chhattisgarh, India. Women Birth. 2018; 31 (2): e122–33.

12. Dai L, Zhang N, Rong L, Ouyang YQ. Worldwide research on fear of childbirth: A bibliometric analysis. PLoS One. 2020; 15 (7 July): 1–13.

13. Ryding EL, Lukasse M, Kristjansdottir H, Steingrimsdottir T, Schei B; Bidens study group. Pregnant women’s preference for cesarean section and subsequent mode of birth – a six-country cohort study, J Psych Obstetr Gynecol. 2016; 37 (3): 75-83.

14. Nilsson C, Hessman E, Sjöblom H, Dencker A, Jangsten E, Mollberg M,

et al. Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18 (28): 1-15.

15. Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021; 6 (6): 1-8.

16. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000; 25 (24): 3186–91.

17. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991; 32 (6): 705–14.

18. Griep RH, Chor D, Faerstein E, Werneck GL, Lopes CS. Construct validity of the Medical Outcomes Study ’ s social support scale adapted to Portuguese in the Pró-Saúde Study. Cad Saúde Pública. 2005; 21 (3): 703–14.

19. Ministério de Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas. Manual de Gestação Alto Risco [

Internet]. Brasília (DF); 2022. [access in 2023 Out 8]. Available from:

https://portaldeboaspraticas.iff.fiocruz.br/atencao-mulher/manual-de-gestacao-de-alto-risco-ms-2022/20. Guimarães NM, Freitas VCS, Senzi CG, Gil GT, Lima LDSC, Frias DFR. Partos no sistema único de saúde (SUS ) brasileiro: prevalência e perfil das partutientes. Braz J Dev. 2021; 7 (2): 11942–58.

21. Mello RSF, Toledo SF, Mendes AB, Melarato CR, Mello DSF. Medo do parto em gestantes. femina. 2021; 49 (2): 121-8.

22. Wiklund I, Edman G, Ryding E, Andolf E. Expectation and experiences of childbirth in primiparae with caesarean section. BJOG. 2008; 115 (3): 324-31.

23. Mortazavi F, Mehrabadi M. Predictors of fear of childbirth and normal vaginal birth among Iranian postpartum women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21 (316): 1–12.

Authors’ contributionBergamini LL: conceptualization (Lead), Data curation (Equal), Investigation (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Project administration (Equal), Validation (Equal), Writing - original draft (Lead), Writing - review & editing (Equal).

Nascimento Silva PH, Barretto Filho EP: conceptualization (Equal), Data curation (Equal), Investigation (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Visualization (Equal), Writing - review & editing (Equal).

Costa ADPV: Methodology (Equal), Project administration (Equal), Software (Equal), Supervision (Equal), Visualization (Equal), Writing - review & editing (Equal).

Melo Neto VL: conceptualization (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Project administration (Equal), Supervision (Equal), Validation (Equal), Visualization (Equal), Writing - review & editing (Equal).

Medeiros ML: conceptualization (Equal), Investigation (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Project administration (Lead), Supervision (Lead), Validation (Equal), Visualization (Equal), Writing - review & editing (Equal).

All authors approved the final version of the article and declare no conflicts of interest.

Received on August 20, 2023

Final version presented on September 7, 2024

Approved on September 9, 2024

Associated Editor: Leila Katz

; Pedro Henrique do Nascimento Silva 2

; Pedro Henrique do Nascimento Silva 2 ; Eduardo Pereira Barretto Filho 3

; Eduardo Pereira Barretto Filho 3 ; Auxiliadora Damianne Pereira Vieira da Costa 4

; Auxiliadora Damianne Pereira Vieira da Costa 4 ; Valfrido Leão de Melo Neto 5

; Valfrido Leão de Melo Neto 5