ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: to evaluate high-risk pregnant women's oral health perception and associated factors during dental prenatal care.

METHODS: observational cross-sectional study, developed in the city of Itapemirim-ES, with seventy-six high-risk pregnant women who answered a structured questionnaire with twenty questions, referring to the sociodemographic profile, pregnancy, use of dental services and perception of oral health, in the period of June to September 2021. Data were descriptively evaluated, and simple logistic regression models were estimated for each independent variable with the outcome, perception of oral health, grouped into very poor/poor and fair/good/excellent.

RESULTS: most women were over 20 years old (78.9%), housewives (60.5%), and considered their oral health to be excellent/good/regular (85.5%), understand that they should take better care of their teeth during pregnancy (92.1%), but 39.5% did not receive guidance on dental treatment during pregnancy. Pregnant women who do not feel that they should take better care of their teeth during pregnancy are more likely to consider their oral health to be very poor or poor (OR=7.75, CI95%= 1.33-45.12).

CONCLUSIONS: pregnant women understand that care and habits related to oral health are important during pregnancy. Inadequate perception of the importance of oral care during pregnancy was associated with a negative self-perception of oral health.

Keywords:

Pregnant woman, High risk, Oral health, Prenatal care

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: avaliar a percepção em saúde bucal de gestantes de alto risco e fatores associados durante o pré-natal odontológico.

MÉTODOS: estudo transversal observacional, desenvolvido em Itapemirim-ES, com 76 gestantes de alto risco que responderam a um questionário estruturado com 20 perguntas, referentes ao perfil sociodemográfico, à gestação, uso de serviços odontológicos e percepção em saúde bucal, no período de junho a setembro de 2021. Os dados foram avaliados de forma descritiva e estimados modelos de regressão logística simples para cada variável independente com o desfecho, percepção em saúde bucal, agrupada em péssima/ruim e regular/boa/excelente.

RESULTADOS: a maioria tem mais de 20 anos (78,9%), é do lar (60,5%), e considera sua saúde bucal como excelente/boa/regular (85,5%), entende que deve cuidar melhor dos dentes durante a gravidez (92,1%), 39,5% não receberam orientações sobre tratamento dentário na gestação. Gestantes que não acham que devem cuidar melhor dos dentes durante a gravidez têm mais probabilidade de considerar a sua saúde bucal como péssima ou ruim (OR=7,75, IC95%= 1,33-45,12).

CONCLUSÕES: as gestantes têm entendimento de que os cuidados e hábitos relacionados à saúde bucal são importantes na gestação. A percepção inadequada em relação à importância dos cuidados bucais durante a gravidez associou-se a uma autopercepção negativa da saúde bucal.

Palavras-chave:

Gestante, Alto risco, Saúde bucal, Consulta pré-natal

IntroductionThe

Política de Assistência Integral à Saúde da Mulher (PAISM) (Comprehensive Women’s Health Care Policy) guidelines state that when starting prenatal care, pregnant women should be referred to a dental appointment to begin prenatal dental care

1, which aims to provide greater safety for pregnant women in risky situations through differentiated care flows.

2 Pregnancy should not be considered the reason for postponing dental care, and it is often necessary to demystify beliefs and myths that many pregnant women have about the risks of care during this period.

3,4During the pregnancy period there are numerous systemic manifestations, where hormonal and emotional disturbances are of great importance to the health professionals involved.

5 Oral manifestations are associated with these changes and are directly linked to factors related to hygiene, such as cavities and periodontal disease.

6,7 In addition, studies have shown the occurrence of premature births and birth of low birth weight babies associated with oral diseases during pregnancy, with a close relationship between hormonal changes during pregnancy and the appearance of oral pathologies.

1,8Inserted in this process of maternal and child dental care, there are high-risk pregnant women, represented by those whose pregnancy involves greater chances of complications to the life of the mother or fetus when compared to the average pregnancy.

2Given the increased risk posed by this special group of pregnant women, high-risk prenatal care is important for reducing morbidity and mortality,

9 requiring greater attention to this section of the population, with educational actions on oral health and the formulation of specific integrated care strategies by different health professionals, including the dental surgeon, with the aim of providing timely monitoring of these changes to avoid additional risks to the health of mother and baby.

2,10,11In order to better accommodate this special group of pregnant women, the city of Itapemirim-ES, in line with the Ministry of Health guidelines on

Atenção Integral à Saúde da Mulher (Comprehensive Women’s Health Care), started at the

Atenção Primária à Saúde (APS) (Primary Health Care) project in 2018 aimed in caring for women at high gestational risk, carried out by a multi-professional team that includes a dental surgeon and an oral health assistant.

Health education is important for changing the view that many pregnant women have about dental care during pregnancy, given that when they have access to accurate and up-to-date information about the care they need for their oral health, they become more aware and confident about dental treatment.

11 In this way, the perception of pregnant women becomes an important indicator for their willingness in taking care of their oral health and adhere to dental treatment. The aim of this study was to assess the oral health perceptions on high-risk pregnant women attending a women’s center in the city of Itapemirim-ES.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional observational study carried out in the city of Itapemirim, in the State of Espírito Santo, with an estimated population of 34,656 inhabitants and

a Índice de Desenvolvimento Humano Municipal (IDHM) (Municipal Human Development Index) of 0.654.

All 91 high-risk pregnant women seen at the

Programa de Saúde da Mulher Casa Rosa (Casa Rosa Women’s Health Program), regardless of their gestational trimester in 2021, were invited to take part in the study. Care is provided by a multi-professional team made up of an oral health assistant, a dental surgeon, a gynecologist, a nutritionist and a psychologist.

Data was collected in person during prenatal consultations at

Casa Rosa, from June to September 2021, using a self-administered questionnaire containing 18 questions designed according to the study by Lazzarin

et al.

11 regarding socioeconomic aspects, oral health status, use of dental services and perception of oral health during pregnancy. To this questionnaire, two questions were added about the trimester of pregnancy at the time of the study and in which trimester they started prenatal care.

For the statistical analysis, absolute and relative frequency distribution tables were constructed and then the simple logistic regression models were estimated for each independent variable with the outcome: perception of oral health assessed by the question: What is your perception of your oral health? The answer was categorized as excellent/good/regular or very bad/bad.

The variables that showed

p<0.20 in the individual analyses (crude) were inserted into a multiple logistic regression model. The final model consisted of the variable that remained with

p<0.05 when the multiple model was tested. The fit of the model was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The odds ratios were estimated from the regression models with the respective 95% confidence intervals. The analyses were carried out using the R Core Team program,

12 with a significance level of 5%.

This study was approved in June 2021 by the Research Ethics Committee of

Faculdade São Leopoldo Mandic, under opinion no. 4.806.033. CAAE- 47769221.6.0000.5374.

ResultsOf the total of 91 high-risk pregnant women seen in 2021, 15 refused to take part, resulting in a sample of 76 pregnant women representing an adherence rate of 83.5%.

Most of the women were over 20 years old (78.9%), housewives (60.5%), had concluded high school (35.5%), were not in their first pregnancy (65.8%), were in the first trimester of pregnancy (47.4%) and considered their oral health to be excellent/good/regular (85.5%). With regard to dental appointments, 57.9% had been to the dentist for less than two years and used the

Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS) (Public Health System) (68.4%) and 35.5% reported not going to the dentist (Table 1).

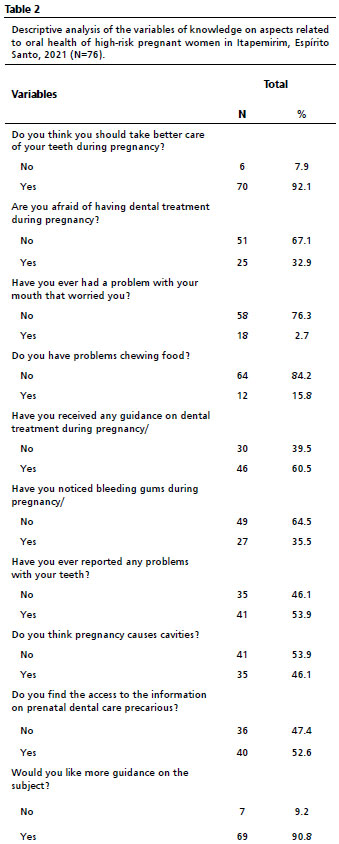

Table 2 shows that the most of high-risk pregnant women believe that they should take better care of their teeth during pregnancy (92.1%); that a significant proportion say that they have received guidance on dental treatment during pregnancy (60.5%); that the most did not have any problems with their mouths that caused any concern, nor problems chewing food, nor have they noticed bleeding gums during pregnancy; however, 53.9% reported having experienced problems with their teeth during pregnancy and that 46.1% believe that pregnancy causes cavities. The vast majority of pregnant women (90.8%) would like more guidance on the subject.

Table 3 shows the analysis between the association of the variables studied and the perception of oral health. The variable “Do you think you should take more care of your teeth during pregnancy?” remained significant in the final model (

p<0.05), (OR=7.75, CI95%= 1.33-45.12),

p<0.05.

DiscussionThe sample studied included pregnant women of different ages, schooling levels and occupations. Understanding these characteristics can enable better effectiveness of healthcare, ensuring a more patient-centered approach. Most of the pregnant women in this study were young, housewives, with a high school education and who had already had other pregnancies. In terms of age, this profile contradicts two studies carried out with high-risk pregnant women which showed an average age of 32 years

2 and 29.2 years

3 and corroborates the predominance of housewives and high school graduates as the highest level of schooling.

1-3The literature shows that individuals with a higher level of schooling have a better understanding of their state of health,

5 which can be correlated with this study, since most of the pregnant women interviewed had a positive assessment of their oral health.

Most of the pregnant women reported having started prenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy, in line with the recommendations of the Ministry of Health. However, a considerable proportion of pregnant women reported that they had not yet been to a dental appointment, which should have taken place early in the pregnancy.

13,14 The purpose of this appointment is to detect and treat possible risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes and to promote maternal and child health. In addition, guidance should be given on oral hygiene, the harmful effects of the pacifier and bottle use and the promotion of healthy eating, including encouraging breastfeeding and the negative effects of sugar.

4,8The Ministry of Health recommends that professionals from the

Estratégia Saúde da Família (Family Health Strategy) or APS teams who start monitoring the prenatal care of pregnant women should refer them to the oral health teams of reference, so that care can be offered as soon as possible,

8 bearing in mind that the establishment of a bond between the dental surgeon and the pregnant woman is a potential element for adherence to the care recommended by the oral care team.

3It was found that although most of the pregnant women said they were not afraid of undergoing dental treatment during pregnancy, a representative proportion did have this fear. The methodology of this study did not allow this association to be assessed, but considering the percentage of pregnant women who said they had not been to the dentist in the last two years, it raises the hypothesis that this fear could be influencing their search for a dentist. The lack of adherence to dental care during pregnancy is linked to a number of factors, such as popular beliefs (risks of anesthesia, bleeding, dangers to the baby), lack of perception of needing treatment, since they often believe that toothache is associated with the condition of pregnancy.

1,2,15,16 These beliefs and myths that treatment can be harmful to the baby, the expectation of pain and insecurity can result in low adherence to prenatal dental care associated with the complications of access, socioeconomic, cultural and educational aspects.

17Therefore, it is necessary to exchange information between dental surgeons and other professionals on the team, as well as to carry out health education activities with the whole community in order to demystify dental treatment during prenatal care.

3,18This reinforces the importance of health education as a tool to elucidate beliefs that make it impossible for pregnant women to seek dental treatment during pregnancy and to maximize adherence to this care.

2,19In this present study, a significant proportion of pregnant women said they had not received any instruction on dental treatment during pregnancy. This fact is noteworthy because high-risk pregnant women are referred to

Casa Rosa for care via the APS units in the city. Considering that the first prenatal consultation is carried out at the APS, pregnant women should already have been instructed on dental treatment. because it is up to this level of care to maintain the bond of caring for a more complete and effective approach for the pregnant woman and her baby by including them in the health education activities and groups.

20When asked about their perception that pregnancy causes cavities, just under half of the respondents answered in the affirmative, which corroborates the findings in the literature,

6,11,19,21 where there was a perception of ignorance in relation to the factors that lead to the development of cavities.Due to physiological changes, pregnant women are more vulnerable in developing oral diseases such as cavities, due to changes in eating habits such as increased intake of sugary foods, associated with nausea and vomiting, which reduces the frequency of daily hygiene and increases the risk.

5,7The way people perceive their oral health can influence their attitudes, motivation and practices related to oral hygiene and seeking dental care.

11 In this study, high-risk pregnant women who did not think they should take more care of their teeth during pregnancy were more likely to consider their oral health to be poor or bad. Thus, the lack of understanding of the importance of intensifying this care during pregnancy can lead to a false sense of security and the idea that there is no need to go to the dentist for follow-up during pregnancy.

16 Thus, a positive perception of oral health is associated with self-care behaviors, such as regular oral hygiene, healthy eating and visits to the dentist.On the other hand, a negative perception can lead to neglect this basic care.

22Considering the methodology used, this study may have some limitations that should be taken into account for the interpretation and validity of its results. We can consider the cross-sectional design, which did not make it possible to estimate the temporal evolution of the aspects that influence the perception of the importance of oral health during pregnancy. The findings cannot be generalized to the entire population due to the sample size analyzed, its regional panorama, the local reality regarding the practice of prenatal dental care and the use of convenience sampling, although it is capable of providing input for new research, given that most studies on oral health are carried out with regular pregnant women and not those at high risk.

However, these limitations do not detract from the importance of the findings since they serve as a basis for characterizing the importance of the dental surgeon in monitoring high-risk pregnant women, emphasizing the need to invest in the permanent qualification of health professionals involved in prenatal care and increase the knowledge of these pregnant women about the importance of dentistry during prenatal care and collaborating with oral health planning and practices for this population.

References1. Farias LG, Araújo JHP, Medeiros JAS, Catão, MHCV, Coury RMMMSM, Medeiros CLSG. Avaliação dos Conhecimentos sobre Saúde Bucal por Gestantes em Atendimento Pré-Natal. Arch Health Invest. 2022; 11 (3): 476-81.

2. Galvan J, Bordim D, Fadel CB, Alves FBT. Fatores relacionados à orientação de busca pelo atendimento odontológico na gestação de alto risco. Rev Bras Saúde Matern Infant. 2022; 21 (4): 1143-53.

3. Brito GMS, Bocassanta ACS, Gutiérrez RMS, Gomes SPM. Percepção materna sobre a importância do pré-natal odontológico na estratégia de saúde da família. Rev Human Med. 2022; 22 (2). [

Internet]. Available from:

https://humanidadesmedicas.sld.cu/index.php/hm/article/view/2340/1471#license4. Schwab FCBS, Ferreira L, Martinelli KG, Esposti 3.CDD, Pacheco KTS, Oliveira AM. Santos Neto ET. Fatores associados à atividade educativa em saúde bucal na assistência pré-natal. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2021; 26 (3): 1115-26.

5. Silva LFA, Borges ECC, Sulzer BG, Silva BLCB, 4.Neto AS. Adesão das gestantes ao pré-natal odontológico em uma unidade de saúde da família do município de Campo Grande/MS. PECIBES. 2022; 8 (1): 16-47.

6. Líbera JD, Santana MRO, Carvalho MM, Simonato 5.LE, Souza JAS, Fernandes KGC. The importance of dental prenatal in baby’s oral health. Braz J Dev. 2021; 7 (10): 101236-47.

7. Lopes IKR, Pessoa DMV, Macêdo GL. Autopercepção do pré-natal odontológico pelas gestantes de uma Unidade Básica de Saúde. Rev Ciênc Plural. 2018; 4 (2): 60-72.

8. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Nota Técnica Nº 15/2022-SAPS/MS. Atualiza ao indicador 3 do Programa Previne Brasil. Online, 2022. [access in 2022 Ago 22]. Available from:

https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/composicao/saps/previne-brasil/componentes-do-financiamento/pagamento-por-desempenho/arquivos/nota-tecnica-no-15-2022-saps-ms-indicador-39. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas. Manual de gestação de alto risco [

Internet]. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2022. [access in 2022 Nov 16]. Available from:

https://portaldeboaspraticas.iff.fiocruz.br/atencao-mulher/manual-de-gestacao-de-alto-risco-ms-2022/10. Gadelha IP, Aquino PS, Balsells MMD, Diniz FF, Pinheiro AKB, Ribeiro SG, Castro RCMB. Qualidade de vida de mulheres com gravidez de alto risco durante o cuidado pré-natal. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020; 73 (Supl. 5): e20190595.

11. Lazzarin HC, Poncio CJ, Damaceno RDP, Degasperi JU. Autopercepção das gestantes atendidas no sistema único de saúde sobre o pré-natal odontológico. Arq Mudi. 2021; 25 (1): 116-27.

12. Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

http://wwwR-projectorg/ 2022. [access in 2022 Nov 16]. Available from: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/157423187404357875213. Soncini E, Santos MD, Menezes EBC, Vieira SN, França KL, Gaia PMC,

et al. Linha de Cuidado Integral sobre a Saúde Materno Infantil. Rev Tec Cient CEJAM [

Internet]. 14º de abril de 2023 [access in 2023 Mai 9]; 2: e202320015. Available from:

https://revista.cejam.org.br/index.php/rtcc/article/view/e20232001514. Silva EDA, Silva MRP, Morais YJ, Kervahal PA. Importância do pré-natal odontológico: uma revisão narrativa. Res Soc Dev. 2021; 10 (15): 1-10.

15. Mesquita LKM, Torres ACS, Vasconcelos Filho JO. Percepções de gestantes sobre o pré-natal odontológico. Cad ESP. Fortaleza. 2022; 16 (1): 49-56.

16. Oliveira LF, Silva DS, Oliveira C. Favretto CO. Percepção sobre saúde bucal e pré-natal odontológico das gestantes do município de Mineiros-GO. Rev Odontol Bras Central. 2021; 30 (89): 116-27.

17. Fumagalli IHT, Lago LPM, Mestriner SF, Bulgarelli AF, Mestriner Junior W. Percepções e atitudes de primigestas em relação à atenção em saúde bucal materno-infantil: um estudo qualitativo. Rev Odontol Bras Central. 2021; 30 (89): 44-63.

18. Cunha AA, Moraes MF. O pré-natal odontológico: contribuição da ESF, atendimento integral e conhecimento, uma revisão da literatura. Arq Ciênc Saúde UNIPAR Umuarama. 2022; 26 (3): 671-80.

19. Amorim LMC, Labuto MM, Babinski JW. Saúde bucal das gestantes: a importância da realização do pré-natal odontológicono município de Guapimirim. Cad Odontol Unifeso. 2022; 4 (1): 75-83.

20. Sampaio JRF, Vidal SA, Goes PSA, Bandeira PFR, Cabral Filho JE. (2021). Sociodemographic, Behavioral and Oral Health Factors in Maternal and Child Health: An Interventional and Associative Study from the Network Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18 (8): 3895.

21. Saliba TA, Custódio LBM, Saliba NA, Moimaz SAS. Atenção integral na gestação: pré-natal odontológico. Rev Gaúch Odontol. 2019; 67: e20190061.

22. Pacheco KTS, Sakugawa KO, Martinelli KG, Esposti CDD, Filho ACP, Garbin CAS, Garbin AJI, Neto ETS. Saúde bucal e qualidade de vida de gestantes: a influência de fatores sociais e demográficos. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2020; 25 (6): 2315-24.

Authors’ contributionLugato VPM: preparation of the project; literature review; conceptualization; preparation of the data collection instrument; data collection; formal analysis; investigation; writing of the manuscript; design of the methodology; validation; formal analysis; discussion of the manuscript. Flório FM: study supervision; writing guidance; final revision. Souza LZ: study supervision; writing of the manuscript; methodology design; writing guidance; final revision. All the authors have approved the final version of the article and declare no conflicts of interest.

Received on June 13, 2023

Final version presented on August 19, 2024

Approved on August 20, 2024

Associated Editor: Alex Sandro Souza

; Flávia Martão Flório 2

; Flávia Martão Flório 2 ; Luciane Zanin de Souza 3

; Luciane Zanin de Souza 3